Inequality in the Arab region:

Rights Denied, Promises Broken

Introduction

Throughout 2024, the Arab region saw diverging fortunes. Conflict, war and occupation continued to

affect

a third of the countries in the region. Humanitarian emergencies and the risk of famine became more

severe, and the risk of a regional war became greater.

Temperatures in the Arab region continued to increase above the global average, with some

countries

experiencing deadly heatwaves. Prolonged droughts in several countries significantly reduced

agricultural

production, severely affecting overall economic activity. Rising sea levels pose a growing threat to the

region, increasing the risk of disease outbreaks and further diminishing an already limited water

supply.

These climate change impacts are accompanied by substantial economic costs and financial implications.

On the economic front, some countries continued to struggle with economic instability, while

others made

gains. Rich countries have continued to benefit from high oil prices, which are expected to last into

2025.

The price of oil is projected to remain above $80 a barrel throughout the year.

Moreover, many Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have used their natural resource wealth

to

accelerate economic diversification by fostering sectors such as tourism, the digital economy, renewable

energy, logistics and trade, and creative industries and culture. In parallel, they are creating an

enabling

environment to attract foreign investment, enhance the competitiveness of their private sectors and

generate job opportunities for their citizens. These efforts are intended to drive sustainable economic

growth, reduce societal inequality and ensure equitable development over the medium to long term.

By contrast, several other countries in the region faced severe economic pressures in 2024, with

five

countries working to contain double-digit inflation that disproportionately eroded the spending capacity

of

low-income households. Exchange-rate depreciation stemming from underlying economic weakness have

widened inequalities between wealthier households with access to savings and foreign currencies and

those without, further exacerbating socioeconomic divides. The resulting emergence of parallel exchange

rates has prompted many Governments to impose capital controls and restrict withdrawals – measures that

often place an undue burden on vulnerable households with limited access to alternative financing or

insurance to manage unexpected emergencies.

Of the 17 countries for which public-debt data is available, seven have public-debt levels above

60 per cent

of gross domestic product (GDP), which indicates an increased risk of debt distress. High public-debt

levels incur high repayment costs and limit Governments’ access to further financing, which affects

their

ability to provide social services to their populations.

Under the prolonged economic stress affecting many countries in the region, seven countries are

either

enrolled in International Monetary Fund (IMF) programmes or are currently negotiating them, including

three countries where negotiations have stalled. These programmes often mandate fiscal consolidation or

austerity measures, which impose significant hardships on low-income households.

Economic, climate and other challenges have never had an equal impact on different population

groups

within the same country, including women, persons with disabilities, elderly and young people. Some have

achieved economic gains; others have lost their access to resources, opportunities and livelihoods.

These

unequal consequences have resulted in a deepening divide within and among countries, and exacerbated

existing inequalities.

Social protection – encompassing social insurance, social assistance and labour-market

programmes –

plays a crucial role in supporting low-income households during challenging times and preventing middle-

income households from sliding into poverty. These programmes are essential not only for providing

opportunities and protection across individuals’ lifespans but also for addressing community-wide

shocks.

Furthermore, social protection contributes to economic development and redistribution; over the medium

to

long term, it reduces inequality and fosters social cohesion.

However, inequalities in social protection coverage and financing compound existing issues.

Unequal

access to social protection benefits or inadequate coverage as a result of limited fiscal space mean

that the

most vulnerable groups, who are already disadvantaged, face greater challenges. Also, depending on their

design and implementation, social protection programmes can themselves reinforce inequality and the

exclusion of certain groups of people.

The study has five chapters. The first chapter sets the scene by highlighting key-social

protection

developments in the Arab region that have either stimulated or limited equality, including income

inequality.

The second chapter explores how social protection systems across the Arab region have influenced

inequality. Given the limited availability of data, the analysis focuses on the comprehensiveness of social protection systems in Arab countries and their relationship to inequality, mostly from an income perspective but also

paying attention to multidimensional inequality and deprivation. The chapter provides an overview of the

patterns and limitations of inequality and social protection. The third chapter examines the experiences

of

different population groups in benefiting from social protection. The fourth chapter examines four case

studies: Oman, Morocco, Jordan and Tunisia; it analyses the role of social protection policies in

addressing

inequalities within these countries, and assesses whether they succeeded in narrowing the gap between

the population groups. The fifth chapter provides policy options to capitalize on social protection to

reduce

inequalities.

1. Setting the scene

Key messages

Early social welfare systems did not sustainably reduce inequalities, largely owing to insufficient creation of decent, formal private-sector employment.

The replacement of regressive general subsidies with targeted cash transfers has led to reduced social spending while slightly reducing income inequality.

Indirect taxes undermine the income gains of poor households provided by cash transfers.

Extending social insurance to “the missing middle” has been only partially successful.

Equitably financed social protection for lifecycle risks such as ill health, old age and maternity can play a role in reducing income inequality.

A. What is social protection?

Social protection protects individuals and households against the financial impacts of life-cycle risks and poverty. In a technical sense, social protection is defined as a “set of public policies and programmes intended to ensure an adequate standard of living and access to healthcare throughout the life cycle. Social protection benefits can be provided in cash or in-kind through universal or targeted non-contributory schemes; contributory schemes, such as pensions; and complementary measures for building human capital, creating productive assets, and facilitating access to employment”.

Social protection is a human right: it applies to everyone throughout their lives, regardless of their level of vulnerability. It is more than a set of technocratic approaches such as social insurance and social assistance. Instead, it is aimed at managing the financial risks associated with life-cycle events and poverty.

Social protection has significant indirect effects that are crucial for policymaking across sectors. This study emphasizes the importance of looking beyond income inequality, and beyond the immediate protective and supportive roles of social protection. Notably, social protection can address other dimensions of inequality and generate indirect benefits, such as enhancing human capital, promoting economic development and fostering social cohesion.

B. How can social protection influence inequality?

To understand the unique capacity of social protection to address inequality, it is essential to look beyond which groups are not sufficiently covered by social protection measures, and to analyse the financial sources of social protection spending.

Equitably financed social protection against lifecycle risks such as ill health, old age, maternity and childcare and other individual life-cycle risks is considered to be one of the most effective policy approaches to address inequality. This chapter explores the approaches that Arab countries have taken to establish social-protection systems to manage these life-cycle risks, the inherent limitations and contradictions of these policy choices, and effective social protection policy designs that Governments in the region could apply to further reduce inequality through progressively financed social protection systems and programmes.

Unsustainable levels of consumer subsidies and public employment were key elements of several Arab countries’ social contracts, while social insurance coverage against life-cycle risks remained at low levels. During the twentieth century, countries in the region established social welfare systems that incorporated large-scale public employment, publicly provided social services and consumer subsidies. These approaches were successful in certain aspects, yet faced challenges in reducing inequality, given that they were not accompanied by effective translation of economic growth into decent, socially insured employment in the private sector. Unfortunately, increasing fiscal imbalances eventually forced many countries to undertake reforms to reduce public employment and social spending. Meanwhile formal private sector job-growth struggled to grow commensurately with increasing numbers of labour-market entrants, leading to an increase in informality. The relatively low productivity associated with informal economic activity in turn trapped several countries in the region in the middle-income bracket. As a result of this vicious cycle, social-insurance coverage in the region plateaued at a relatively low level, effectively slowing down income redistribution through direct taxation and contributions to social insurance funds.

More recently, general subsidies were phased out to a large extent, while cash transfers aimed at reducing poverty were introduced across most countries in the region. In recent decades, several Arab countries grappling with rising public debts and low levels of revenue collection sought to phase out regressive general consumer subsidies, replacing them with social assistance programmes aimed at reducing poverty. While these reforms have improved the reach of cash transfers to cover a significant proportion of poorer people, the effectiveness of social protection in reducing income inequality remained constrained by factors such as adequacy, equitability and sustainability of financing.

C. Turning points in social protection policy decisions affecting equality

The austerity measures in recent decades and their impact are the result of interlinked policy choices.

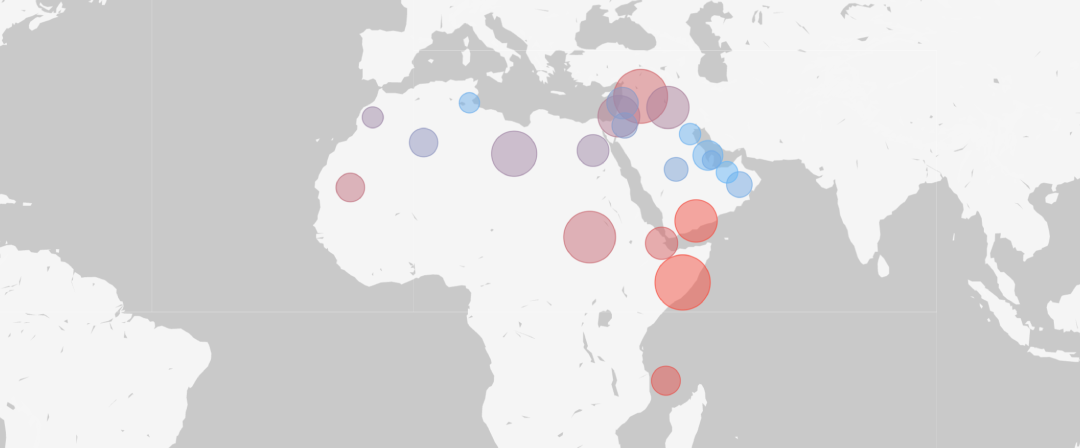

Social policy choices which affect inequality do not happen in a vacuum. Instead, they have knock-on effects in the form of political and economic changes. Some policy choices have resulted in the stagnation of social-protection coverage – particularly in comparison with developments observed in other regions such as Latin America and East Asia. Figure 1 depicts the experience of many Arab countries in a general way, though there are various differences between contexts.

Figure 1. Timeline of political and economic events and social insurance coverage in Arab countries

Social insurance regimes in the region have changed over time, but have not gained much traction beyond the shrinking public sector, thereby limiting their redistributive capacity. Contributory social protection regimes (i.e. social insurance schemes) were introduced in the Arab region during the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century; they were focused on providing protection to State employees against a limited number life-cycle risks. Eventually, these systems were expanded to cover a wider range of risks, such as disability and widowhood. They were also extended to some private-sector employees, though coverage within this group plateaued early on. In addition, the provision of public employment and social services increased substantially, and general subsidies on energy, food and other basic products became common across the region.

The expansion of social protection, other tax-financed social services and public employment coincided with a considerable reduction in multiple dimensions of inequality. For instance, in Egypt, the Gini coefficient of consumption expenditure fell from 0.42 in 1958 to 0.38 in 1974. School enrolment and the literacy rate also increased considerably, especially among girls, putting countries in the region on the path towards gender parity.

Fiscal constraints and related structural adjustment policies affected Governments’ scope for redistribution. In the 1980s and 1990s, many low- and middle-income countries in the region faced fiscal imbalances and resorted to structural-adjustment programmes. These reforms entailed a reduction in public-sector employment, often implemented through hiring freezes. Meanwhile, despite economic growth, relatively few new jobs were created in the formal private sector, thereby additionally limiting the further expansion of social insurance provision and in turn constraining the redistribution of income between income levels and economic sectors.

Consumption smoothing by means of general subsidies proved unsustainable. While general subsidies helped in keeping consumer goods affordable, they also proved highly expensive, and sometimes led to cross-border smuggling and shortages. In addition, richer people often derived substantially more benefits from the subsidies in absolute terms – specifically as a result of unequal energy and fuel consumption – than poor and lower-middle-class households.

Recently, social protection systems have been increasingly geared towards greater efficiency and targeted social assistance. By the early twenty-first century, social protection systems in many Arab countries started shifting their focus towards greater efficiency, marked by reforms that reduce public-sector employment, phase out subsidies and expand cash-based social assistance. Subsidy spending has been declining since around 2012, although this trend was partially and temporarily reversed in 2022 following an increase in global energy prices (figure 2). Increased consumer prices have caused household expenses to rise, disproportionately affecting the poorest. This has been coupled with a reduction in public-sector employment opportunities, which has intensified income inequality and strained the middle class. To cushion these impacts and address the rising poverty, Governments have expanded targeted cash assistance (figure 3).

Figure 2. Spending on subsidies as a percentage of GDP

Note: The definition of “subsidy spending” may vary across the countries. For example, for Egypt, “2012” refers to the 2012/13 financial year.

Figure 3. Percentage of population covered by selected cash-transfer programmes

D. Where we now stand

Social protection reforms have achieved greater efficiency, but not always greater effectiveness. The reduction in subsidies and the increased provision of poverty-targeted cash transfers have meant that a bigger proportion of social assistance spending now reaches poorer people. However, all programmes aimed at reducing poverty suffer from imperfect targeting, meaning that not everyone who should receive benefits actually does so. In particular, many of the most marginalized poor people are not reached by any social protection coverage.

Informality remains high despite efforts to extend social insurance. Given relatively low formal employment rates and the extremely low labour-force participation rate of women, social insurance coverage among the population overall is among the lowest globally, which has limited the potential of Arab social-insurance systems to effectively redistribute income and subsequently reduce inequality. It has been estimated that only around one third of the labour force in Arab countries contributes to a pension scheme.

Figure 4. Outset scenario

Figure 5. Post-reform scenario

An emerging “missing middle” has fallen between the cracks of poverty-targeted social assistance schemes and formal-employment-based social-insurance coverage. The increased focus on poverty-targeting has also ushered in a limited focus on monetary poverty at the expense of other dimensions of vulnerability, including those associated with life-cycle events such as maternity, disability and old age. In the context of persistent informality, the reduction in subsidies has led to the emergence of new forms of inequality: those who have access to any type of social protection and those who do not. A “missing middle” has emerged, consisting of those people who are not covered by contributory social insurance, but who are nonetheless not considered sufficiently poor to qualify for non-contributory social assistance. The abolition of subsidies has meant that the last type of protection that was previously available to members of this group now no longer exists. Figures 4 and 5 show how an entire population was initially covered by general subsidies, although richer groups benefited more in absolute terms. At the same time, relatively well-off parts of the population were disproportionately likely to be covered by social insurance. Following reforms, general subsidies have been replaced with targeted social assistance. Nevertheless, in practice, not poor people are covered by social assistance, thanks to a combination of budget shortages, targeting errors, and rapid changes in household income, moving them either below or above the poverty line within a short period of time. Meanwhile, social insurance remains limited to the relatively well-off.

Poverty targeting has not always translated into more resources for the poor. The redistributive impact of poverty targeting is also determined by the total amount of resources allocated to social assistance. In many countries, substantially increased spending on targeted cash transfers corresponds only to a small fraction of the amounts previously spent on general subsidies. For instance, the ESCWA Social Expenditure Monitor shows that between 2012 and 2021, subsidy spending in Jordan as a proportion of GDP declined by 4.3 percentage points (from 4.5 to 0.2 per cent of GDP), while spending on direct income support increased by merely 0.6 percentage points (from 0.4 to 1 per cent of GDP).

Social protection spending levels overall – while they have increased slightly in recent years – remain lower than they were. In Egypt, spending on subsidies decreased from 8.8 per cent of GDP in the 2013/14 financial year to 3.2 per cent in 2023/24, while spending on social benefits (including social insurance and social assistance) increased from 1.1 to 1.8 per cent of GDP (figure 6). This suggests that additional spending on direct social assistance may only partially compensate for the socioeconomic impact of subsidy reductions. In other words, while the focus of social protection spending has slightly shifted towards poorer people, the overall amount made available for social protection has substantially decreased.

Figure 6. Social spending (subsidies and social benefits) in Egypt (Percentage of GDP)

Note: For the financial years up to 2021/22, actual spending is shown. For the 2022/23 financial year, estimated spending is shown. Figures for the 2023/24 financial yearare taken from the State budget.

Indirect tax regimes disadvantage poor and vulnerable groups. Taxation generally makes up a smaller part of central government revenue in Arab countries than it does elsewhere (figure 7). In Arab countries, however, a relatively high share of tax revenue comes from indirect taxes such as value-added tax as opposed to direct taxes such as income and corporate taxes, suggesting that taxation in the region is likely to be relatively regressive. In some instances, beneficiaries therefore experience a reversal of the income gains achieved by cash transfers.

Figure 7. Composition of central government revenue (global averages vs. Arab region)

Note: Unweighted averages based on countries with available data.

Effective income redistribution works through universal pooling of contributions to life-cycle protection through national social insurance funds. Countries in the Arab region have often established separate social insurance funds for different employment sectors. The members of these limited insurance schemes have tended to have relatively homogeneous income levels, which has significantly limited the schemes’ capacity to redistribute income. Recently, policymakers – have increasingly opted to merge smaller social insurance schemes for individual occupation groups into unified national social insurance funds. An example of this is the comprehensive social protection reform of 2023 in Oman, which merged 11 individual insurance funds into one major social protection fund (see Oman case study). Crucially, this facilitates income redistribution, since different income groups – including high, medium and low earners – contribute to the same scheme, providing them with similar benefits.

Integrated social assistance and social insurance schemes can protect all income groups against life-cycle risks and reduce income inequality. A more redistributive social protection system therefore goes beyond enlarging tax-financed social assistance, but requires extending contributory systems to include earners across the income spectrum so that higher earners can cross-subsidize the lower contributions of those who earn less. Efforts to extend social insurance coverage are at times undermined by the ever-increasing enrolment of poor and near poor populations into social assistance programmes aimed solely at reducing poverty. This is unfortunate, since being a contributor to or recipient of a pension scheme is sometimes an exclusion criterion for being eligible for these programmes, thereby posing a disincentive for some near-poor people to join national social insurance schemes. Partly for this reason, countries are increasingly adopting life-cycle-based social-insurance schemes, whereby the contributions of those with limited capacity to pay are fully or partly subsidized by the State, and social assistance and social insurance coverage are not necessarily mutually exclusive. For instance, in 2023, Mauritania launched a health-insurance regime for informal workers. Workers pay a fixed annual contribution, of which two thirds is paid by the Government.

2. Social protection comprehensiveness and its impact on inequality: a struggle to improve

Key messages

Algeria, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia lead the Arab region in implementing inclusive social protection measures supported by substantial financial resources.

Countries with universal coverage, comprehensive protection of lifecycle risks and higher social-protection expenditure tend to have lower levels of both income and multidimensional inequality.

Several middle-income countries established effective, comprehensive social protection systems with relatively low levels of resources.

Upper-middle-income countries with more formal economies are struggling to provide key benefits, such as employment insurance and maternity benefits, particularly those associated with contributory schemes.

Consumption-based subsidies, such as subsidies for energy and fuel, exacerbate inequality by disproportionately benefiting wealthier households.

Cash transfers can reduce persistent income inequality by breaking the intergenerational poverty cycle in concert with improved education, skills upgrade and health services and broad-based economic growth.

A. Social protection comprehensiveness: stepping forward from the past

In an effort to understand the relationship between Arab countries’ social-protection systems and their effects on inequality, the report establishes the comprehensiveness of these systems using a comprehensiveness assessment referred to as the Social Protection Comprehensiveness Index (SPCI). The methodology used in this analysis relies on information available from the International Labour Organization (ILO) and ESCWA (table 1); it was inspired by a methodological proposal using information from Latin American countries to assess their social protection systems.

Table 1. Indicators for the Social Protection Comprehensiveness Index

Universality

Universal Health Service Coverage Indexa

Proportion of population covered by at least one social protection benefit (excluding health)b

Risk comprehensiveness

Proportion of older persons receiving a pensionb

Active contributors to a pension scheme as percentage of the labour forceb

Proportion of unemployed people receiving benefitsb

Proportion of children (0 to 18 years old) covered by social protection benefitsb

Proportion of women giving birth covered by maternity benefitsb

Proportion of workers covered in case of employment injuryb

Persons with severe disabilities collecting disability social protection benefitsb

Proportion of vulnerable persons receiving benefits (social assistance cash benefits)b

Social spending

Actual general government expenditure on social protection, excluding healthcare (percentage of GDP)b

Domestic general government health expenditure (GGHE-D) as percentage of gross domestic product (GDP)c

The Social Protection Comprehensiveness Index (SPCI) goes beyond conventional assessments of coverage and spending. It provides an integrated snapshot of the extent to which national systems address the full range of social protection contingencies—including unemployment, workplace injury, maternity, disability, and lack of economic opportunities. The SPCI reflects the degree to which countries are building inclusive systems that meet the needs of all population groups, aligned with international standards for comprehensive protection.

The index relies on publicly available data analyzed by the ILO and WHO, drawn from government reports, international sources, and household surveys. However, major data gaps persist. In many Arab countries— particularly those affected by conflict or institutional fragility—reliable information is scarce. Even in more stable contexts, irregular reporting and limited public data hinder an accurate picture of effective coverage.

Strengthening data availability, integrating social protection modules in national surveys, and improving transparency are essential to reflect actual conditions, and better capture the full scope of government efforts and policy progress. These steps are critical for countries working toward more inclusive and accountable social protection systems.

As illustrated in figure 8, the 2023 Social Protection Comprehensiveness Index reveals significant disparities in social protection systems across Arab countries. Countries with a high comprehensiveness index such as Algeria, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia have robust social-protection frameworks, scoring consistently high across all components of the index. These countries have successfully implemented inclusive social protection measures, underpinned by substantial financial resources. Conversely, countries with a moderately comprehensive system, such as Egypt, Jordan and Kuwait have solid social-protection systems, but show some variability, particularly in risk comprehensiveness. While these countries provide a range of protections, they do not fully address all lifecycle contingencies.

Countries with emerging systems – such as the Comoros, the Sudan and Yemen – exhibit significant limitations across all aspects of social protection. Yemen, for example, has an SPCI score of just 0.14, with particularly low scores in universality (0.14) and social spending (0.09), highlighting a lack of effectiveness in reaching vulnerable populations. Outliers such as Somalia and Djibouti show mixed results. Somalia, with an SPCI score of 0.16, has notable gaps in universality (0.06) despite a relatively higher social spending score (0.30), indicating a misalignment in resource allocation. (Watch a short film featuring with the Minister of Labour and Social Affairs of Somalia, Yusuf Mohammed: https://youtu.be/2_ENOYP1mkM). Djibouti, with an SPCI of 0.20, also faces challenges, though its scores in risk comprehensiveness (0.21) and social spending (0.18) are slightly better.

On the other hand, among lower-middle-income countries, Tunisia stands out with a strong SPCI of 0.76, driven by solid arrangements in universality (0.77) and social spending (0.87). The country’s social spending score is the second highest in the region after Kuwait. This indicates a significant financial commitment from the Government, even though the income level of Tunisia is not the highest of all Arab countries. In conflict- and war-affected countries such as Iraq, Somalia, State of Palestine, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen, the analysis reveals additional complexities: conflict and war have severely affected these countries’ abilities to implement effective social protection systems, as demonstrated by their low SPCI scores.

Figure 8. Arab countries' social protection comprehensiveness in 2023

The modest overall level of risk comprehensiveness in high-income countries suggests that these countries, despite generally high levels of coverage in terms of social protection and health, do not offer significant coverage for various life-cycle risks (figure 9). In several cases, this could be due to the exclusion of specified groups, such as informal workers, the lack of national or public arrangements, such as social health insurance, and, in some instances, a preference for private providers, thereby limiting redistribution between income groups.

Figure 9. Arab countries' risk-comprehensiveness in the SPCI in 2023

Countries with higher GDP per capita generally achieved better scores on the SPCI in 2023 (figure 10). High-income countries such as Saudi Arabia and Bahrain scored well, with Bahrain leading as a result of its high scores in universality (0.91) and social spending (0.65). However, certain countries in this group have lower SPCI scores than might be expected given their income levels. Qatar, with a score of 0.34, and the United Arab Emirates, with a score of 0.41, are examples of this. This discrepancy could be attributed to aspects of risk comprehensiveness, as both countries have lower scores in this component. Upper-middle-income countries such as Algeria (0.80) and Tunisia (0.76) also scored well, with comparable scores to high-income countries.

Figure 10. GDP per capita (Current United States dollars) vs. SPCI score

B. Linking social protection comprehensiveness to income inequality

A slightly negative relationship can be observed between social protection comprehensiveness (measured by the SPCI) and income inequality as measured by the Gini index (figure 11). Countries which score highly on the SPCI tend to achieve better outcomes in terms of reducing income inequality. For instance, Algeria, with a high SPCI score of 0.8, has a robust social safety net with high universality (0.9) and substantial social spending (0.8), potentially contributing to a low Gini coefficient of 26.9 in 2022.

In contrast, inequality in high-income countries is more complex. Bahrain, for instance, scored 0.7 on the SPCI, indicating a relatively strong social protection framework. However, its Gini coefficient in 2022 was 36.2, suggesting higher levels of income inequality than in other high-income countries. On the other hand, Qatar, despite a surprisingly low SPCI score of 0.3, had a Gini coefficient of 22.4 in 2022. This suggests that in some high-income countries, income redistribution is influenced by more than just social spending. It may also be affected by factors such as the lack of national pooling of contributions across different income groups, and a preference for private insurance or public services funded by non-tax revenue, which limits income redistribution. The relationship between income, inequality and social protection is rendered even more complex by factors such as education, job opportunities and the structure of the economy, all of which also play a role in shaping income inequality.

Lower-middle-income countries have achieved varying levels of social protection comprehensiveness and inequality. In Tunisia, which has an SPCI score of 0.8 and a Gini coefficient of 35.0, comprehensive social insurance coverage against life-cycle risks could be contributing to reducing inequality. Conversely, the Comoros has an SPCI score of 0.15 and a Gini coefficient of 50.0, reflecting severe challenges in providing adequate social protection, which may be contributing to income inequality and exacerbating existing disparities.

Figure 11. SPCI vs Gini coefficient (2022)

In-depths analysis: six Arab countries’ approaches to social protection and their impact on income equality

Chapter 1 illustrates how countries’ social protection policies have shifted from general subsidies to targeted cash transfers, leading to a greater proportion of overall social spending being concentrated on poorer people. However, the impact of this shift on poverty and inequality will depend on the total amount of resources allocated to social spending, and – crucially – on how those resources are mobilized. High indirect taxes, such as value-added tax on essential goods, can diminish the intended benefits for low-income households, as taxes of this kind have a disproportionate effect on less prosperous population groups. This is a significant concern: in many countries in the region, taxes on goods and services constitute a significant portion of overall tax revenue, ranging from 40 per cent in Morocco to 70 per cent in Jordan.

Understanding the balance of different tools that Governments use to redistribute income and reduce inequality and poverty is essential to understanding the broader role of social protection beyond financial protection against life-cycle risks. To this end, this section estimates the impact on households’ income of taxes and benefits, including both direct transfers, such as cash transfer programmes and indirect transfers, such as the provision of public education and healthcare. As a result, it is possible to determine how different segments of the population are affected and measures the regressivity or – conversely – pro-poor characteristics of programmes and interventions, providing insights into the effectiveness of government policies in redistributing wealth and reducing inequality.

We have assessed the impact of taxes and benefits on income inequality by applying this approach on available data from six countries – Tunisia (data from 2010), the Comoros (2014), Iraq (2017), Morocco (2017), Djibouti (2017) and Jordan (2018). Figure 12 shows the difference in income inequality in terms of Gini coefficient (left axis) between market income (income from private sources before taxes and transfers) and final income (including all taxes and transfers). The dark blue bar represents the Gini coefficient measured based on market incomes, the orange bar represents the Gini coefficient measured based on final net incomes, and the green dot indicates the difference between the two (right axis). These findings predate many important reforms, such as the reduction of general subsidies and the expansion and better targeting of cash-transfer programmes. Still, the results indicate that all countries experienced a reduction in Gini coefficient as a result of a combination of taxes, subsidies, and transfer tools. Specifically, Tunisia in 2010 saw a reduction of 0.10 points, and Iraq saw a reduction of 0.06. The Comoros and Djibouti also reduced income inequality by 0.01 and 0.03 index points respectively.

Figure 12. Gini reduction: market income after taxes, transfers and subsidies

In Tunisia, cash transfers contributed modestly to redistribution. This modest effect was due to the country’s approach to targeting, and to the limited size of budget allocations (chapter 1) – the programme accounted for only 0.15 per cent of GDP. The country’s cash-transfer programme, like other social programmes, is designed to be pro-poor, targeting the poorest 20 per cent of society, although the richest 10 per cent also receive a share of the benefits. Despite this, the overall effect of such programmes is significantly progressive and equalizing. Subsidies are less effective in terms of redistribution than cash transfers because non-poor people benefit from them disproportionately. Overall, spending on education and health in Tunisia is equitably distributed across income groups.

The fiscal system of Iraq plays a significant role in reducing inequality, primarily through targeted cash transfers and universal benefits. Key programmes include the poverty-targeted Conditional Transfer Programme and the Public Distribution System, which provides households in all income groups, including the poorest, with monthly rations of wheat flour, rice, sugar and vegetable oil. Direct pension transfers also contribute substantially to reducing inequality, with generous public pensions playing a major role (figure 13). However, while these pensions have a significant impact, they have high implementation costs.

Despite these positive measures, the fiscal system faces challenges, particularly as a result of the regressive nature of indirect subsidies. Measures such as petrol subsidies disproportionately benefit wealthier households and exacerbate inequality. Healthcare and education non-cash benefits were excluded from the analysis, leaving gaps in the understanding of the broader impact of fiscal policies on inequality in Iraq.

Figure 13. Marginal contributions to Gini coefficient made by various fiscal interventions in Iraq

In terms of in-kind transfers, the Comoros and Djibouti provide interesting examples. The Comoros uses education and healthcare services as primary tools for reducing inequality, since expenditure in these areas benefits poorer populations. While the Comoros has a progressive income-tax system, the overall impact of in-kind transfers is limited by the low starting point of taxation.

Djibouti also uses in-kind transfers in education and healthcare to reduce inequality, with a particular focus on making these services available to poorer populations. Public primary education spending in Djibouti is evenly distributed; however, educational transfers vary. Lower-secondary education funding is concentrated in middle-income quintiles, and spending on higher levels of education becomes less progressive. Djibouti has significantly expanded its social protection programmes, such as the National Family Solidarity Program, which targets households living in extreme poverty with children aged 16 or younger through an unconditional cash transfer of 30,000 Djibouti francs per quarter (equivalent to $167). These programmes have had a notable impact on poverty reduction. However, the country’s fiscal system is complex, with even the poorest households paying more in taxes than they receive in additional disposable income.

As shown in figure 14, the estimation of the SPCI for 2015 suggests a positive relationship between social protection comprehensiveness and the reduction of income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient. The positive trend confirms the hypothesis for the countries in the sample. Jordan, Morocco and Egypt, for example, exhibit medium to high levels of SPCI comprehensiveness, and have achieved moderate success in reducing income inequality. Although efforts in education and healthcare have contributed to reducing inequality, each country has room for improvement. For example, in Egypt, universal subsidies are seen as less targeted; the indirect taxes applied by Jordan are regressive; and in Morocco, indirect taxes similarly exacerbate inequality. Most countries – possibly with the exception of Tunisia – do not yet redistribute income by pooling social insurance contributions across income groups.

Figure 14. SPCI 2015 and Gini coefficient reduction

C. Multiple inequalities and social protection policies

In many instances, social protection policies are intended to address income inequality directly. However, the relevance of these policies for inequality goes far beyond income. The ESCWA Multidimensional Inequality Framework provides a well-established lens for understanding the relevance of social protection policies for various types of inequalities, for example those related to economic, gender and youth inequalities, and inequalities in access to education, healthcare, food, finance and technology. As the analysis indicates, countries with lower SPCI scores tend to have higher levels of multidimensional inequality overall. This correlation also aligns with country income levels (figure 15).

Figure 15. SPCI vs. ESCWA Multidimensional Inequality Index 22

Chapter 3 provides in-depth insights into the complex relationship between multiple dimensions of inequality and social protection policies and their implementation, in connection with factors such as informality, gender, disability, youth, old age and migration.

D. Indirect and long-term impacts

These insights, however valuable, do not sufficiently capture economic multiplier effects – such as the long-term benefits of investments in education and healthcare and their impact on the likelihood of entering the formal labour market. Income redistribution affects different income groups through interconnected economic sectors. For example, additional income for low-income groups tends to be spent on basic needs, circulating within sectors where poor people are more active, whereas income increases for wealthier groups often benefit sectors that largely exclude vulnerable populations.

Beyond these secondary effects, other long-term impacts on inequality could be expected from social protection programmes, particularly those where the provision of cash transfers is contingent on participants fulfilling certain conditions. Such programmes are intended to help beneficiaries break the intergenerational poverty cycle by encouraging actions and behaviours that improve future outcomes. In principle, they increase the likelihood that the next generation of the most vulnerable people will be successful in entering the formal labour market and securing decent jobs, thus reducing inequalities over time. However, conditions associated with such programmes need to be designed carefully. For example, if conditions are imposed but the inadequacy of healthcare and education provision in a country prevents members of a targeted group from fulfilling them, the programme is unlikely to be effective. Conditional cash transfers can also have other unintended effects: for example, they can increase the caregiving burden of mothers who are too overwhelmed with tasks to meet programme conditions. In addition, access to education and healthcare services is not sufficient to tackle inequalities if the quality of these services does not enable beneficiaries to compete with higher-income individuals in the labour market, or if there are structural issues such as gender discrimination, or if there is not enough demand in the formal labour market, as seems to be the case in a number of Arab countries. These concerns are illustrated by the case of Bolsa Familia in Brazil (box 1).

Bolsa Família is a large-scale conditional cash-transfer programme in Brazil which provides financial aid to poor families in exchange for meeting various health and education conditions. Launched in 2004, Bolsa Família consolidates various social programmes to provide financial aid to the poorest families in Brazil, contingent on their meeting certain health- and education-related conditions such as school attendance and use of prenatal care. The programme supports over 14 million households; this support is based on income levels, and participants’ compliance with conditions is monitored. Since 2023, the programme has been updated. It now has an improved focus on operational efficiency. Various gaps have been addressed, and the programme is now integrated more effectively with social-assistance services, reinforcing its role as a tool in the social policy of Brazil.

The Bolsa Família programme has reduced social inequalities in Brazil by increasing support for families living in extreme poverty and improving access to essential services such as healthcare and education. The programme’s requirements for health check-ups and school attendance have improved healthcare access, reduced child mortality, and boosted school enrolment. Bolsa Família has positively affected social dynamics, including youth labour, women’s decision-making, and education outcomes. By extending benefits to families with teenagers aged 16 to 17, it has increased school enrolment and encouraged studying and working, especially in rural areas and the Northeast/Southeast regions. It has also enhanced women’s decision-making power in urban households, influencing children’s education and health choices. The programme has led to higher school participation and grade progression, especially among girls.

Multidimensional poverty maps, by municipality – Brazil – 2000 and 2010. Data source: Demographic Census

3. Social protection for the most vulnerable: inclusive or exclusive?

4. Closing the divide: lessons from four countries

A. Oman – Comprehensive reforms for universal protection and equality

At the end of 2023, the Government of Oman adopted a comprehensive social protection reform package that completely transformed the country’s social protection provision (details of the reform and its financing is detailed in this video by Laila Al Najjar, Minister of Social Development of Oman: https://youtu.be/pGtZQJmH3m4).

The reform package was aimed at making the entire system substantially more accessible and equitable for all population groups. The reform introduced new contributory and non-contributory social protection schemes across all social groups with the aim of promoting income equality, as well as other dimensions of inequality.

1. Coverage and benefits

Before the reforms, social assistance in Oman primarily targeted vulnerable people, such as persons with disabilities. This at times led to a limited number of beneficiaries receiving multiple benefits, which was ineffective in reducing overall vulnerabilities across groups. This approach resulted in fragmentation and duplication, with minimal impact on inequality and poverty reduction.

Likewise, the existing contributory social insurance system, which comprised 11 distinct pension funds for formally employed workers in the private and public sectors, was not designed to promote redistribution or equality, and did not reach large parts of the population. The system provided benefits (table 2) for contingencies such as old age, disability and employment injury, but with unequal coverage for different categories of workers, leaving many unprotected in the event of key risks. Moreover, fragmentation across professional and income groups limited risk-pooling and redistribution.

Table 2. Social insurance schemes in Oman for various life stages before the social protection reform

Public Authority for Social Insurance (PASI)

X

X

X

X

X (planned)

-

-

-

Petroleum Development Oman LLC Pension Scheme (PDO)

X

X

X

-

-

-

-

-

Central Bank of Oman Pension Scheme (CBO)

X

X

X

-

-

-

-

-

Civil Servant Employees Pension Fund (CSEPF)

X

X

Funeral only

-

-

-

-

-

Diwan Royal Court Pension Fund (DRCPF)

X

X

Funeral only

-

-

-

-

-

Ministry of Defense Pension Fund (MODPF)

X

X

Funeral only

-

-

-

-

-

Royal Oman Police Pension Fund (ROPPF)

X

X

Funeral only

-

-

-

-

-

Royal Guard of Oman Pension Fund (RGOPF)

X

X

Funeral only

-

-

-

-

-

Special Force Pension Fund (SFPF)

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

Internal Security Pension Fund (ISPF)

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

Royal Office Pension Fund (ROPF)

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

No information

In 2023, however, a comprehensive social protection reform changed almost every facet of the country’s existing system. The new system covers the entire population, and comprises non-contributory (social assistance) as well as contributory (social insurance) elements. It spans the full lifecycle, and provides protection against multiple dimensions of inequality.

Under the new system, social assistance benefits are provided broadly to children, persons with disabilities and older persons. Such non-contributory benefits are also provided to orphans and widows not covered by social insurance. A poverty-targeted social assistance benefit is provided to households with low incomes.

The reorganized social insurance landscape provides protection in the event of old age, disability, work injury and occupational disease. Unlike the old system, the new one also covers unemployment, sickness and maternity/paternity. The fact that fathers as well as mothers receive benefits is highly significant from a gender equality perspective and makes Oman a regional pioneer.

Table 3. Summary of the new social protection system in Oman

Implementation of the new system started in 2024; by September of that year, more than 575,000 contributors had enrolled, 89,899 people were receiving old-age pensions, and 30,872 people were receiving survivor’s pensions. Universal non-contributory benefits were being provided to 41,299 persons with disabilities, 167,222 older persons, and 1,229,454 children; pension-tested benefits were being provided to 16,160 widows and orphans; and means-tested benefits were being provided to 41,727 households on low incomes.

Figure 26. Coverage of the Oman Social Protection Fund, September 2024 (Number of people)

Notably from an inequality perspective, significant progress has been achieved through the inclusion of non-nationals in several important schemes, enhancing the social protection system of Oman in line with the principles of the Equality of Treatment Convention in relation to social security. Law 52/2023 ensures that migrant workers will gradually be given access the same benefits as Omanis in areas such as sickness and employment, maternity and paternity and injury insurance.

Furthermore, a national provident fund has been established to replace the current end-of-service indemnities system, simplifying the process for collecting employers’ contributions and administering benefits to non-Omani workers for retirement, death, disability, and when returning to their home countries. This is one important step towards reducing social-protection-related inequalities between citizens and migrant workers upon retirement.

2. Equity and financial sustainability

The total social protection expenditure (excluding health) of Oman amounted to 2.3 per cent of GDP before the reform. This was significantly lower than the regional average of 5.4 per cent of GDP and the global average of 12.9 per cent during the same period.

Following the reform, the 2024 State budget reflects a heightened focus on social protection, with 560 million rials ($1.5 billion, or 4.8 per cent of total expenditure) being allocated to social assistance – a considerable increase on the 384 million rials ($1 billion, or 3.4 per cent of total expenditure) in the 2023 budget. Meanwhile, 750 million rials ($2 billion) are expected to be channelled through the social insurance system in 2024.

The new financing system integrates financing from the general budget with contributions from social insurance. Providing non-contributory old-age, disability and child benefits on a universal basis has the potential to generate broad-based support for the system. However, in order for such a system to reduce inequality, the resources going into it need to be mobilized in a progressive manner.

In 2021, Oman introduced a value-added tax, following other GCC countries. This type of taxation, owing to its regressive nature, could counteract the income-equality-promoting effects of social assistance targeted towards poor and vulnerable people, who usually have to spend a larger proportion of their income on consumption goods. The Government, however, has provided exemptions for items such as essential food to protect low-income populations. In 2024, Oman further made history by instituting a personal income tax for wealthy individuals, making it the first GCC country to do so. This is a significant step towards fostering a fairer, more progressive fiscal structure, and one which will promote income redistribution if social benefits are at least partly financed by this new source of government revenue.

Meanwhile, the integration of numerous existing social insurance regimes into one allows for a higher degree of risk pooling and redistribution across income groups. The consolidation of the various pension funds into a single entity is anticipated to improve the overall efficiency of the pension system. With a more centralized and cohesive structure, the newly merged pension fund is expected to withstand changing economic conditions and demographic trends, ensuring that retirees and future beneficiaries will receive stable and sustainable financial support.

The reform also supported gender-equality efforts, particularly through its approach to maternity and paternity benefits. Under the new law, these benefits are financed by a 1 per cent contribution paid by all employers. Unlike the previous system, where the cost of maternity leave was borne directly by employers, this new policy removes any disincentive to hire women, and thus constitutes an important step in promoting women in the labour market and hence increasing their access to social insurance.

B. Morocco – Significant steps towards health equality

In 2002, Morocco adopted a new, comprehensive health-insurance scheme, known as Assurance Maladie Obligatoire (AMO). Contributory social health insurance coverage was made mandatory for salaried private sector employees and administered on their behalf by the National Social Security Fund (CNSS). Between 2005 and 2016, effective coverage among this group increased from 43 to 82 per cent. To achieve such substantial take-up, the CNSS adopted a range of measures, including workplace inspections and digitized contribution payments.

In addition to AMO, the law instituted a health assistance regime, Régime d’Assistance Médicale (RAMED), to cover poor and vulnerable people. Those identified as belonging to this group consequently enjoyed non-contributory health coverage, financed mainly by the State. RAMED was first piloted in 2008; it was extended to the whole of the country in 2012. By 2018, it covered almost 12,000,000 people.

Among the Moroccan population as a whole, effective health coverage (contributory or non-contributory) increased from 16 per cent in 2005 to 70.2 per cent in 2020. However, the reforms to health insurance brought new challenges, one of which was a lack of coverage for people who were neither salaried employees nor poor enough to qualify for RAMED. This group – largely comprising self-employed workers, as well as those who did not work, but nonetheless were not considered poor – remained without coverage.

Another challenge was that the different components of the health coverage system did not offer the same level of protection. While AMO beneficiaries had access to both public and private healthcare services, RAMED beneficiaries were only entitled to public-sector healthcare (table 4).

Table 4. Statutory health coverage in Morocco before the recent reforms

Increased demand from RAMED beneficiaries led to public hospitals and other healthcare facilities being increasingly overburdened. As a result, even though inequality decreased tremendously in terms of health coverage, it persisted in terms of actual access to adequate healthcare. As shown by figure 27, although out-of-pocket expenditure decreased following the introduction of AMO and RAMED, it remained far above the regional average.

Figure 27. Out-of-pocket expenditure as percentage of current health expenditure

1. Ongoing reforms to attain healthcare equality

To address this type of inequality, additional reform measures were introduced to achieve full health equality. In 2017, Morocco passed legislation extending AMO coverage to self-employed workers; this was gradually implemented from 2020. In 2021, Morocco adopted a new social protection framework law (No. 09/21). The law has four pillars, the first of which concerns the generalization of health insurance coverage (table 5).

Table 5. Pillars and timeframe of law No. 09/21 in Morocco

1.

Generalization of mandatory health insurance coverage

2021–2022

2.

Generalization of family allocations

2023–2024

3.

Increased pension coverage

2025

4.

Generalization of loss-of-employment benefits

2025

As a result, RAMED was abolished in 2022, and replaced with a new non-contributory scheme, AMO Tadamon. The new scheme is an integrated part of AMO, meaning that those covered by it have access to the same healthcare benefits as those who are covered on a contributory basis. Beneficiaries are targeted by means of the country’s new social registry, introduced as part of the overall social protection reform.

In January 2024, a voluntary contributory scheme, AMO Achamil, was introduced to cover economically inactive people who nonetheless have the capacity to pay contributions. As a result of these reforms, statutory social health insurance coverage in Morocco is now universal, with all of the population having equal access to the same benefits package (table 6).

Table 6. Coverage of statutory social health insurance in Morocco after the recent reforms

2. The way forward

The reforms outlined above have positioned Morocco as a regional leader in advancing health access equality. Nonetheless, there are significant challenges ahead. One key issue is ensuring take-up – that is, translating full statutory coverage into full effective coverage – particularly for newly included population categories.

Another challenge lies in mobilizing sufficient financing and ensuring that healthcare staffing levels can meet the added demand for healthcare resulting from expanded coverage. Adding to this, the methodology used for identifying AMO Tadamon beneficiaries may need further refinement to ensure that no one is mistakenly left out.

C. Jordan – Data-driven boosting of equality through the National Unified Registry

The National Aid Fund of Jordan was established in 1986 to mitigate the impacts of economic reforms. By 2018, it provided assistance mainly through a monthly financial-aid programme which covered around 100,000 families. This programme was deemed to have certain shortcomings related to coverage, notably the exclusion of bigger households and working poor people. Therefore, a key strategic objective of the country’s 2015–2019 social protection strategy was to improve the performance and efficiency of social assistance programmes.

In 2019, the National Aid Fund launched a new cash-transfer programme, the Unified Cash-Transfer Programme, which would gradually replace the old monthly financial-aid programme. By the end of 2023, the new programme covered 170,147 households comprising 866,400 individuals, corresponding to around 7.6 per cent of the national population. Meanwhile, the number of people covered by the monthly financial-aid programme had been reduced by around half, to around 1.3 per cent of the population.

Figure 28. Number of households covered by National Aid Fund cash-transfer programmes

The Unified Cash-Transfer Programme targets beneficiaries based on a comprehensive list of 57 indicators chosen as proxies for estimating income. These indicators relate to demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, including disability status, material possessions and type of housing. The indicators are verified through the National Unified Registry, which was launched the same year as the Unified Cash-Transfer Programme. The new registry has a simplified online registration process, which has facilitated the expansion of the new programme.

Figure 29. The National Unified Registry

By 2023, the number of ministries and agencies connected with the new registry had reached 35. The system is also connected with the civil registry and identity system, which encompasses the entire national population.

1. An integrated social protection information system for comprehensive service provision

The current objective is for the National Unified Registry to become an integrated social protection information system, which will include the function of a proper social registry. It will contain data not only on current beneficiaries but also on potential ones. It will also be used to select beneficiaries for multiple programmes operated by different entities, eventually functioning as a “single-window” entry point.

Applications will go through the new registry by default, being evaluated using a unified welfare ranking formula. Applicants may then be referred to one or several of programmes, depending on eligibility. In 2024, a plan was approved to use the new registry for directing applicants towards five additional social protection services, including assistance for persons with disabilities, energy support and health insurance.

Figure 30. Envisioned national unified social registry process

Inam is a mother of nine. In 2016, she and her five sons and four daughters were forced to relocate from Zarqa Governorate to Amman after a retaliatory attack led to their home and belongings being set on fire.

One of Inam’s sons died in prison following the incident. Another remains incarcerated, and a third who sustained a gun injury is currently unemployed. Her fourth son has Down syndrome, while her youngest son is in his final year of school. Three of her daughters are married; the youngest, recently divorced at the age of 20, now lives with her mother. Inam herself suffers from health issues, including burns from the fire and epilepsy.

Inam receives 50 Jordanian dinars per month in assistance from the Jordanian National Aid Fund after learning about it from others. She qualified for aid as a mother of orphans. She also received emergency cash assistance to help replace furniture lost in the fire, and occasionally receives seasonal support, such as assistance during Ramadan. Additionally, her high-school-aged son has been participating in a programme offering online educational support for students (for the full story, see this video: https://youtu.be/EpAMdzRuuNE).

Using the National Unified Registry as a social registry will address multiple dimensions of inequality by ensuring that households receive relevant services and benefits and are assessed equally in terms of their social protection and social service needs. For instance, a person with a disability applying for cash transfers under the National Aid Fund may be referred to disability-specific programmes or services that they would not otherwise have been aware of.

This, in combination with a facilitated registration process, ensures that more people will benefit from specific social protection mechanisms appropriate to their needs, since cash transfers alone cannot effectively tackle all dimensions of inequality.

The National Unified Registry’s enhanced cross-verification functions – for example, verifying land and vehicle ownership statements – will also allow scarce resources to be channelled to those most in need, thereby further reducing income inequality.

2. The way forward

Enabling the National Unified Registry to function as a proper social registry will further enhance both the effectiveness and the efficiency of the national social protection system of Jordan, with positive impacts on poverty and inequality. Additionally, using the new registry to foster economic empowerment – possibly supported by machine-learning-aided job-market information systems – could also promote sustainable poverty reduction, by identifying training needs and matching social assistance beneficiaries with jobs.

However, the unification of structures and processes carries various risks. In the worst case, targeting errors could be multiplied across all programmes that use the registry. It is therefore important not only to ensure that the unified welfare ranking formula is well devised and reliably implemented, but also that there are accessible and effective redress mechanisms in place. Furthermore, processes that are standardized across programmes for different social groups must remain responsive to the specific circumstances and needs of individual vulnerable groups. This is relevant not just in terms of the benefits provided but also in terms of implementation processes (such as outreach, registration, enrolment and payment) that such an integrated information system requires households and individuals to use.

For more details about social protection reform, see this video featuring the Jordanian Minister for Social Development, Wafaa Bani Mustapha: https://youtu.be/n5jJtTxxaYA.

D. Tunisia – Social protection to promote gender equality: new law on parental benefits

Tunisia has one of the region’s most developed and comprehensive social protection systems. In 2024, 54 per cent of the population was covered by at least one form of social protection, far above the regional average of 35 per cent. This is partly due to comparatively comprehensive social insurance coverage, which exceeds that of most other countries in the region.

The Government of Tunisia has taken steps to address one of the system’s longstanding shortcomings, a limited maternity-benefits policy. This issue was particularly significant for women in the private sector, where the duration of leave and financial benefits provided were among the lowest in the Arab region. Recent reforms to maternity-leave policies represent a critical step toward enhancing women’s labour-market participation given the role of maternity insurance in supporting working mothers. It is also a step towards ensuring that both men and women can balance work and family responsibilities without jeopardizing their financial security and career prospects. These efforts come against the backdrop of persistently low labour-force participation in Tunisia, which stood at 24 per cent in 2023, compared with 63 per cent among men, underscoring the need for structural changes to close the gender gap.

Previously, mothers in the private sector were only entitled to four weeks of maternity leave. This short period was well below the minimum standard set by ILO in the Maternity Protection Convention, which provides for a minimum of 14 weeks’ maternity leave at two-thirds pay. Previous legislation did not recognize the role of fathers during childbirth, granting only one day of leave for fathers in the private sector and two days for those in the public sector. This disparity in leave arrangements had contributed to widening the inequality between men and women, putting the burden of postpartum childcare solely on women and consequently pushing them out of the labour market after giving birth.

1. The adoption of the 2024 parental-leave law in Tunisia

In 2024, Tunisia ratified a new law which introduced significant updates to maternity and paternity leave in both the public and private sectors. The new law establishes equal leave rights for employees, addressing maternity and paternity leave with a focus on social justice, gender equality and family support.

2. Key legal provisions

Maternity leave: under the new law, mothers in both the private and public sectors are entitled to maternity leave covering both the pre- and post-natal periods. This includes a maximum of 15 days before the birth and three months after birth, with an extension to four months in the case of multiple births, children with disabilities or other special circumstances. In addition, the law grants mothers the right to breastfeeding breaks for up to one year after returning to work to ensure a balance between work and childcare responsibilities.

Paternity leave: one of the most notable improvements under the new law is the extension of paternity leave, making Tunisia one of the leading Arab countries in this regard. Fathers in both the public and private sectors are now entitled to 7 days’ leave, which can be extended to 10 days in the case of multiple births, children with disabilities or other special situations. The extension of paternity leave is in line with global trends towards more inclusive family policies, recognizing the importance of fathers’ involvement in early childcare.

Job protection and non-discrimination: a key element of the new law is the guarantee of job protection during maternity, paternity and breastfeeding leave. The law explicitly prohibits the dismissal or punishment of workers on the grounds of pregnancy or childbirth. Employees in both the public and private sectors are guaranteed to retain their rights to career advancement, promotion and retirement during these leave periods. This protection is an important step in fostering an environment where workers, especially women, do not have to choose between career advancement and starting or growing a family.

3. The way forward

The new parental-leave law of Tunisia is an essential part of the country’s broader social protection reforms aimed at promoting a more inclusive and equitable society. However, continued monitoring, enforcement and adjustments are necessary.

While the law harmonizes leave entitlements, significant challenges remain in addressing financial disparities between the public and private sectors. Although the length of leave has been equalized across both sectors, inequalities in pay persist. Mothers working in the public sector are entitled to their full salary during maternity leave, whereas those in the private sector receive an allowance equivalent to two thirds of the average daily wage. This allowance is capped at twice the minimum wage and does not include employer contributions. This disparity underscores the financial inequalities between the public and private sectors and indicates the need for further reforms to fully achieve the objectives of the law.

Private-sector concerns about the financial burden of compliance highlight the need for supportive measures such as government subsidies and tax incentives. The requirement to apply for the allowance within one month of childbirth adds another layer of administration that can be burdensome for mothers navigating the postpartum period.

While the recognition of the father’s role in childcare is a positive development, the provision of only seven days of paternity leave is still insufficient and undermines the goal of shared parental responsibility.

5. Social protection reform pathways for more equal and cohesive societies

To effectively reduce inequality, social protection systems and programmes need to be universal, progressively financed, and responsive to the needs of vulnerable groups. This requires Governments to plan economic development in conjunction with social policies, and vice versa.

Broad-based economic growth is key to ensuring that opportunities are created in sectors that foster socially insured, decent employment. At the same time, budgets need to be planned and implemented with a view to limiting unintended negative effects, such as the unintentional exclusion of people without access to poverty-targeted social assistance or employment-based social insurance. To avoid this, Governments may find it beneficial to reduce the legal, administrative and financial factors which make it difficult for informal workers and low-income self-employed to enrol in national social insurance schemes, such as by temporarily co-financing their social insurance contributions.

Figure 31 illustrates the broad principles of an integrated and universal social protection system (figures 4 and 5 in chapter 1). In this example, non-contributory support is not limited to the poorest, but also covers the middle section of society, where it can partly take the form of co-financed social insurance contributions. The level of this support is gradually discontinued for those who have a certain level of earnings, while the level of benefits provided through the system always increases in line with incomes.

Figure 31. A universal social protection system

Extending social insurance coverage and consolidating funds provides higher potential for reducing inequality though risk pooling across income groups. At the same time, social assistance programmes need to be progressively financed. An excessive reliance on resource collection through regressive measures such as value-added tax risks undermining the redistributive impact of cash transfers. Direct taxation, such as through personal or corporate income tax, is generally more equitable. However, it currently plays a relatively small role in the Arab region. Furthermore, in order for social protection to effectively reduce inequalities, including multidimensional ones, it is essential that design and delivery mechanisms be adapted to the various life-cycle needs and often overlapping vulnerabilities of different groups, notably women, older persons, young people, persons with disabilities and migrants.

1. Actions for fair redistribution through social protection

At macro level, the following social protection reforms can be advanced to guarantee universal and progressive social protection in support of redistribution while leaving no one behind:

-

1. Ensure fair financing of social assistance.

Non-contributory social protection can have an inequality-reducing impact if it is accurately targeted and equitably financed. It has a greater impact if it is financed through progressive forms of taxation – for example, personal and corporate income tax – rather than regressive indirect taxation such as value-added tax.

-

2. Progressively move towards enrolling all informal workers in unified social insurance funds.

By bringing a higher number of workers – including self-employed workers with relatively high incomes – into risk and contribution pools, Governments can reduce the need for further expansion of social assistance resulting from unprotected exposure to life-cycle risks such as poor health, old age and maternity/childcare. Depending on the context-specific reasons for informality, measures to be taken may include awareness and advocacy campaigns, simplification of procedures, and labour inspections at larger companies to enforce effective social insurance coverage for workers that employers have not registered.

-

3. Prioritize investments in accessible quality education and healthcare.

Social services, including healthcare and education, often complement social protection programmes, which stimulate demand for these services – notably in the case of conditional cash transfers. To enable the effective human capital accumulation that could break the poverty cycle and promote equality, it essential that such services are not only accessible, but also of good quality.

-

4. Ensure the adequacy of benefits.

While horizontal expansion (adding more beneficiaries) may often be a necessity the desired impacts in terms of poverty and inequality reduction will not materialize if benefits are too low. Especially in contexts of high inflation, it is therefore essential to have indexation mechanisms in place that maintain the purchasing power of beneficiaries.

-

5. Integrate economic and social policy planning.

Social protection policies should not be conceived in a silo, as they are closely connected with macroeconomic and other policies. Integrated and coherent policy planning should be aimed at translating economic growth into the creation of formal private-sector-driven employment that is socially insured against life-cycle risks, and to ensure that social protection policies are conducive to such growth.

-

6. Introduce and facilitate enrolment in unemployment insurance.

When introducing unemployment insurance schemes such as those currently being arranged in Tunisia and planned in Morocco, options should be considered which allow informal workers to join. Policymakers might consider subsidizing these workers’ contributions and simplifying procedures with a view to providing short-term benefits for temporary periods of unemployment.

2. Actions to improve social protection policy design and delivery for the most vulnerable