Social Expenditure Monitor for Arab States

Toward making budgets more equitable,

efficient and effective to achieve the SDGs

Foreword

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) confirm the need to revisit and expand fiscal space, and to calibrate expenditure for effective and inclusive social programmes that “leave no one behind”. Accordingly, fiscal choices must be sustainable and responsive to societies’ changing needs. The roles of government budgets became central in recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic. They are now equally imperative in mitigating complex and compounded global risks, including inflationary pressures, the spillover effects of the war in Ukraine, and the climate crisis. Unless these risks are well managed, and vulnerable segments of the population are protected with adequate social services and social protection, achieving macroeconomic and political stability and realizing the SDGs will become increasingly farfetched. The role of public social expenditure in achieving these objectives is crucial, given that it underpins the wellbeing and economic potential of individuals and societies. It protects poor and vulnerable populations, stabilizes small and medium enterprises and economies, and enhances resilience to cope with and recover from crises. Consequently, the present report makes the case that public social expenditures should not be viewed as optional handouts from Governments to people or as a financial cost, but rather as essential investments in human capital, drivers of greater productivity and correctors of inequity. To capture concrete evidence of how expenditure choices intersect with crucial social development priorities in the Arab region, the present report, jointly produced by the Economic and Social Commissions for Western Asia (ESCWA), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), provides vital information on improving policy choices across the following seven social expenditure dimensions aligned with the SDGs: education; health and nutrition; housing and community amenities; labour market interventions and employment generation; social protection, subsidies and support to farms; arts, culture and sports; and environmental protection. The report offers a number of new findings that are highly relevant for policymakers at this critical juncture of the post-COVID recovery. It details how public social expenditures in Arab countries can be enhanced in terms of adequacy, equity and efficiency. Public budgets targeting vulnerable populations, including people living with disabilities, refugees and immigrants, are facing intense pressures, both cumulative and as a result of recent events. Moreover, little expenditure is aimed at women and young people. Addressing inequality, vulnerabilities and low productivity, and stimulating more social mobility, require expanding the coverage and quality of services, and developing social security mechanisms for workers in the informal sector and for older persons outside the formal pension system. Even before the pandemic, already limited fiscal space was under increasingly intense pressure. Today, fiscal space has been further tightened by pandemic responses and by concurrent global shocks from rising inflation and interest rates. Arab countries are therefore facing difficult questions around enhancing social expenditures, while maintaining fiscal sustainability. Nonetheless, solutions that extend beyond the status quo are within reach. Based on the evidence, the report stresses that “enhancing” not only means spending more but also spending smarter. The Arab region could greatly benefit from efficiency gains in public expenditure, allowing countries to save significant resources while achieving the same outputs, or to channel savings into potentially greater results. There is also a strong call for prioritizing equity in social spending, which entails considering the equity implications of how resources are raised and spent to benefit the poorest and most vulnerable social groups. Many of these solutions need to be developed into a comprehensive and integrated approach, encompassing all aspects of human development. The report argues that better monitoring and assessment of social policies, improved allocation of public expenditures to vulnerable populations and overlooked sectors, and sound public finance management can all go far in steering social expenditures that contribute most effectively to sustainable and inclusive development. The report’s recommendations can support Arab countries in devising budgets equipped for making a powerful and lasting contributions to recovery and the SDGs. At a time of enormous pressures in the Arab region and worldwide, countries are looking more than ever for high-impact development solutions and tools. The present report can offer ways to make public budgets work for the wellbeing of all people across the region.

Key messages

In the wake of the devastating COVID-19 pandemic and amid global macroeconomic uncertainties, including the spillover effects of the war in Ukraine, inflationary pressures and the climate crisis, adequate, equitable and efficient social spending is more important now than ever.

On average, public social expenditure in the Arab region, as a share of GDP, is lower than the global average. Arab Governments devote about 8 per cent of GDP to health, education and social protection, compared with the world’s average of 20 per cent. Total social expenditure, capturing the seven dimensions of the SEM, varies across Arab countries between 10 to 20 per cent of GDP.

Social sector financing in the Arab region depends largely on inequitable financing mechanisms, where the contribution of publicly pooled resources to social sector financing lags behind the global average. Public funding pools should be promoted as the most equitable fundraising mechanism, with an emphasis on progressive and effective tax systems. Private financing mechanisms can also be utilized to complement the drive for improved equity in access and outcomes.

Government effectiveness and control of corruption indicators are stronger predictors of social expenditure efficiency than the size of social expenditures. Countries can be more efficient even without high levels of social expenditure.

It is important to improve domestic revenue mobilization by increasing tax collection, reassessing the tax base, enhancing tax equity and progressivity, addressing tax inefficiencies, and controlling illicit financial flows given the scale of tax revenue leakages and abuses, such as tax evasion, trade misinvoicing and tax avoidance. Increasing tax collection should involve investing in quality public services that inspire trust and create buy-in among taxpayers.

PFM reform is a pressing priority for Arab countries to progressively tackle PFM system bottlenecks in accordance with a roadmap that factors in country specificities, including the strengths and weaknesses of existing systems and national resources and capacities, noting that core PFM functions should be prioritized.

1. Why does public social expenditure matter?

ESCWA, in partnership with Jordan and Tunisia, developed the Social Expenditure Monitor (SEM) to inform current budget choices and “smart spending” for the SDGs. UNDP and UNICEF have joined the initiative given that social policy and related fiscal aspects are placed at the heart of their daily work in the region.

Key messages

In the wake of the devastating COVID-19 pandemic and amid global macroeconomic uncertainties, including the spillover effects of the war in Ukraine, inflationary pressures and the climate crisis, adequate, equitable and efficient social spending is more important now than ever.

Fiscal policy aimed at reducing poverty and inequality can both spur growth and accelerate social justice and human wellbeing. SEM helps to optimize links between expenditure choices and macroeconomic objectives, provides a basis for better statistics, and strengthens advocacy for much-needed fiscal policy reforms.

The Social Expenditure Monitor (SEM) presents a new framework for measuring social expenditures in the following seven dimensions by capturing critical social development priorities aligned with the SDGs: education; health and nutrition; housing, connectivity and community amenities; labour market interventions and employment generation; social protection, subsidies, and support to farms; arts, culture and sports; and environmental protection.

Arab countries face difficult questions around the fiscal sustainability of enhanced social expenditures. The present report stresses that “enhancing” means not just spending more but spending smarter.

A. Lagging on development and now constrained on expenditure

After

the global economic downturn in 2008 and the

slow recovery that followed, the cracks in the social

contract accelerated amid rising demands for

employment and better-quality public services.

Evidence suggests that in most countries,

including in Arab states, increased education

spending, as a share of Government expenditure,

raises the primary school enrolment rate (figure 1).

Figure 1. Higher spending on education tends to boost school enrolment rates, average 2017-2019

Inadequate public spending is reflected in the region’s low number of hospital beds per capita as well as in high out-of-pocket expenditure on health care (figure 2).

Figure 2. Fewer hospital beds per capita reflects inadequate public health expenditure, average 2017-2019

Just 40 per cent of people in the region is covered by at least one social protection cash benefit (figure 3). Coverage gaps are particularly large for women, youth and non-national workers, including refugees, given low labour force participation and high levels of unemployment and informal employment.

Figure 3. Many groups in the Arab region lack effective social protection coverage compared to the rest of the world, 2020 or latest available year

B. Moving beyond the trade-off mentality

One question for policymakers in recent

years—and now highly relevant in mapping

a post-pandemic future—has centred on the

perception of a trade-off. Social expenditures

have conventionally been seen as having value in

reducing poverty and inequality but not necessarily

in enhancing economic growth. This report argues

that the notion of a trade-off between a fairer

society and a more efficient economy should be

put aside.

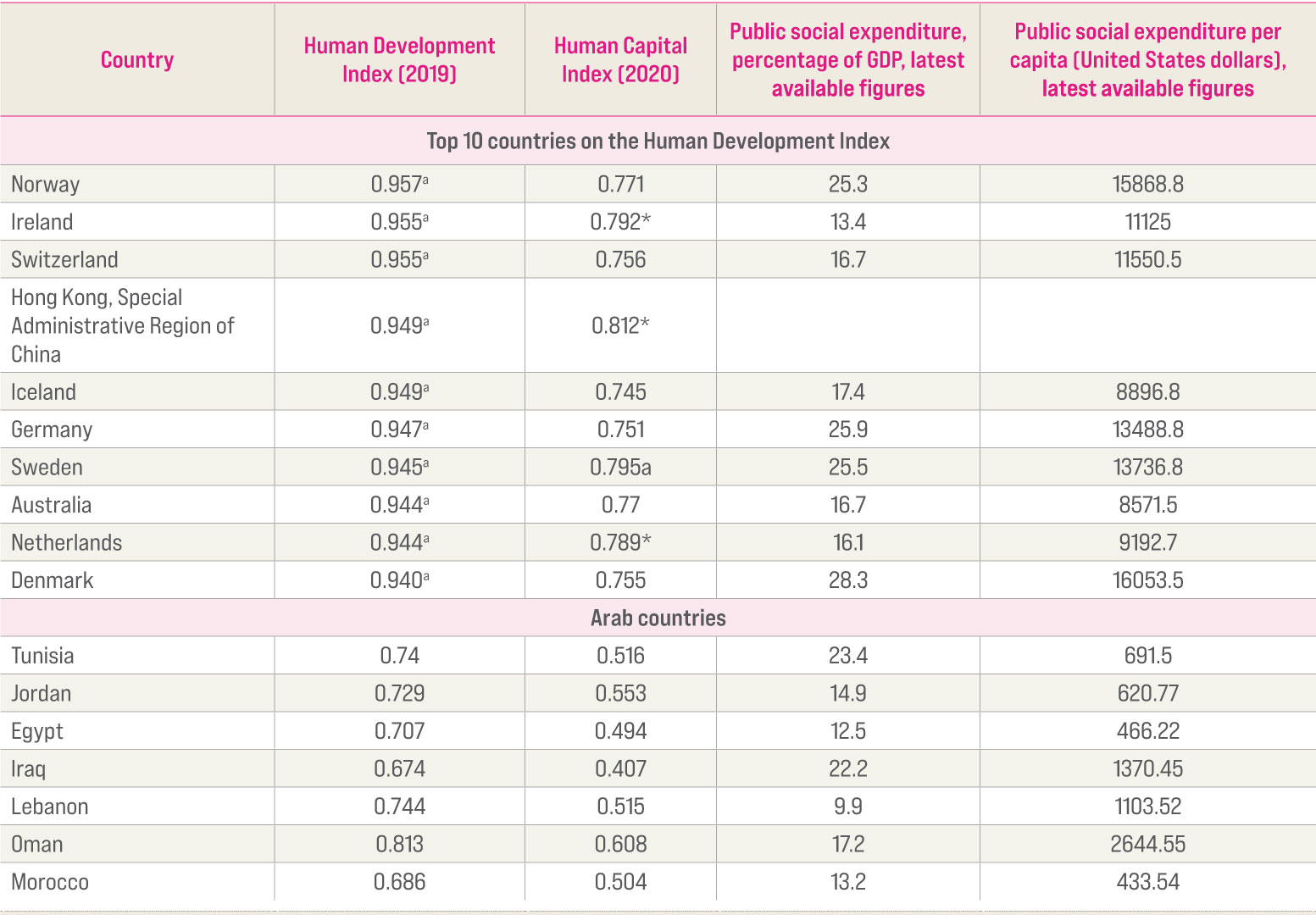

Most of the top 10 countries globally in terms of

human development have high human capital;

in contrast, Arab countries typically have low

human capital (table 1). The International Monetary

Fund (IMF) suggests that to achieve five SDGs

central to boosting human, social and physical

capital, the median Arab State must increase

public expenditure by 5.3 per cent of GDP per year

between 2020 and 2030.

Table 1. Countries at high levels of human development have high scores on human capital

Note: Public social expenditures are compiled from OECD and ESCWA databases for OECD and Arab countries respectively.

C. A better means of measurement

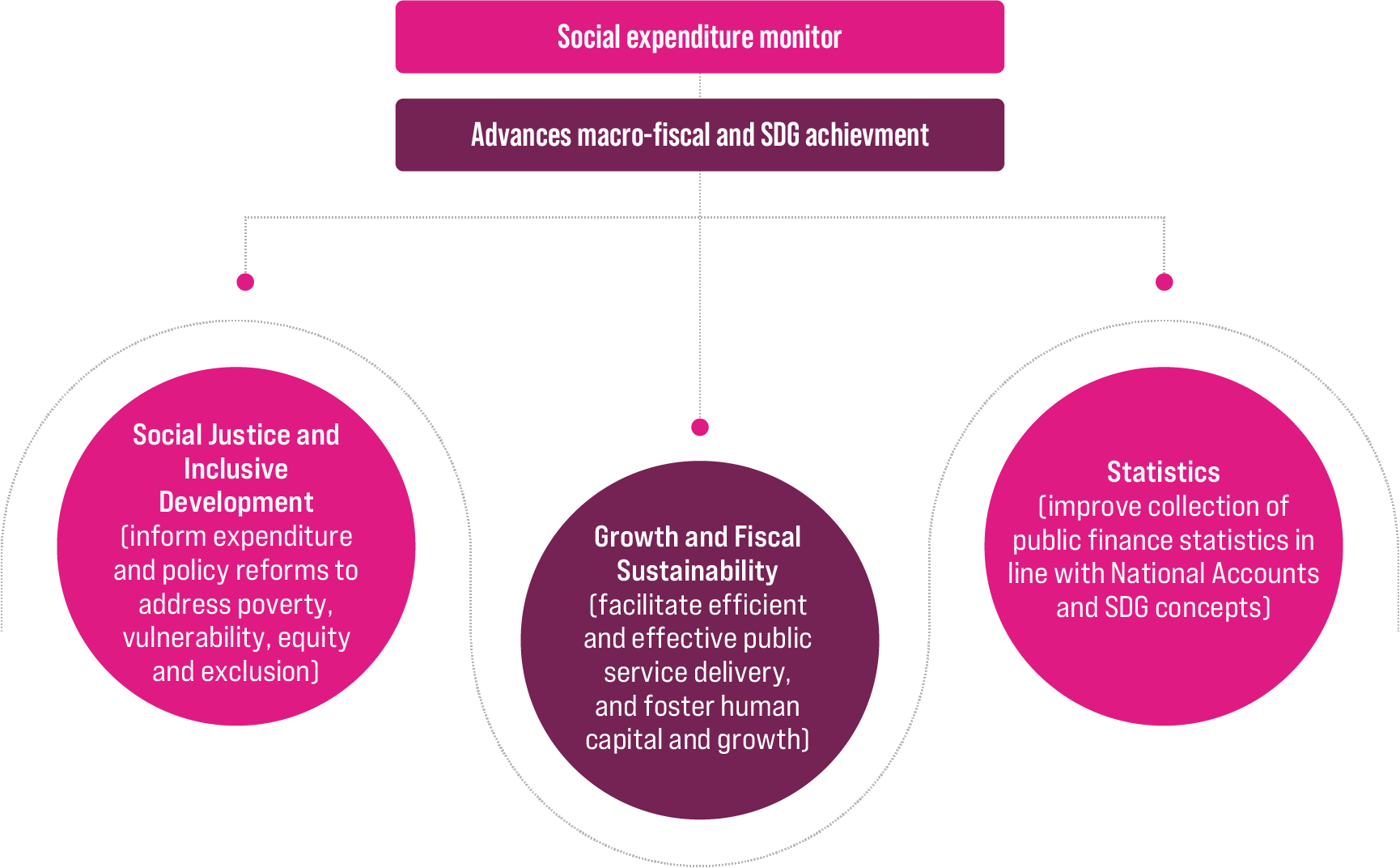

Given the critical role of public social expenditure and the pressures on fiscal space, this report presents the SEM as a tool to align spending with progress on multiple SDGs (figure 4). Many Arab countries currently lack holistic monitoring of social expenditure, which undercuts efficient and effective budget choices. Compounding these gaps are ineffective coordination among ministries and insufficient tools for social expenditure and fiscal sustainability analysis.

The SEM helps demonstrate why fiscal policy should not be restricted to redistribution through social assistance, social insurance and transfers. It can assist in steering fiscal policy towards a much larger role in reducing poverty and vulnerabilities and ensuring inclusive development and social justice (figure 5). It supports rationalizing social expenditures and finding the right mix of social protection and social investment to enhance human capital, kickstart opportunity and innovation, and realize the productivity and economic participation of all members of society. All these investments contribute in turn to greater macroeconomic and social stability.

Figure 5. The SEM helps advance the SDGs by monitoring budgets and fiscal policy reforms

2. Measurement to guide smart spending

Key messages

On average, public social expenditure in the Arab region, as a share of GDP, is lower than the global average. Arab Governments devote about 8 per cent of GDP to health, education and social protection, compared with the world’s average of 20 per cent. Total social expenditure, capturing the seven dimensions of the SEM, varies across Arab countries between 10 to 20 per cent of GDP.

Social spending is dominated by current expenditures, limiting prospects for capital spending. For countries with available data, SEM finds that about 80 per cent of public social expenditure is current expenditures, mainly in the areas of wages and salaries and public transfers. Governments need to steer resources towards improving capital spending in social policy areas to generate jobs, encourage private sector investments, and foster productivity.

SEM shows shortfalls in critical areas of social spending that build capacity among young people, promote startups through labour market support, generate jobs, incentivize creativity in arts, culture and sports, and build resilience through greening and protecting the environment. In addition, public budgets often lack a clear framework for tagging budget lines to beneficiaries, which risks progress on critical SDG targets including promoting gender equality, improving social security coverage, and fostering inclusive growth.

It is necessary to reprioritize public budgets and steer allocations to critical social policy areas and the neediest populations. Governments should therefore consider a balanced mix of expenditures. In many cases, this will involve improved targeting of public transfers to social protection programmes addressing poverty and vulnerabilities, and investing in human capital that drives greater productivity and economic growth.

A. Measuring social expenditure in public budgets

1. What is social expenditure?

The definition of social expenditure varies

across countries. One global measure captures

Government budget spending on health, education

and social protection. Known as HES, it is produced

by the IMF, covering some core elements of the

SDGs but not others.

The SEM defines social expenditure as

including goods and services provided to

individuals, households or communities,

primarily on a non-market basis but also

through subsidies, grants, tax relief and

other transfers. It classifies on-budget social

expenditure in seven dimensions (table 2).

2. Challenges in mapping public budgets

- First, the level of disaggregation often does not allow the clear identification of specific social services and target beneficiaries.

- Second, the economic classification of social services is often not reported.

- Third, budget classifications may not be comparable over time.

- Fourth, sources of expenditure are not consolidated in the general Government budget or central Government budget.

- Finally, most countries do not make a detailed budget document publicly available.

3. Adding up the numbers: comparing the SEM and other measures

A calculation of the HES and SEM based on public budget shares in 2019 found higher total expenditure, as a share of GDP, under the SEM (figure 6). The difference was highest in Iraq (13.8 per cent) followed by Tunisia (7.8 per cent) and Oman (7.4 per cent). The difference was lowest in Jordan and Morocco.

Figure 6. The SEM developed by ESCWA compared to the HES developed by IMF, 2019

Note: In the HES, social protection does not include subsidies and support to farms. Data on SEM are from public budgets. In the case of Lebanon, subsidies to fuel and electricity are treasury advances to the electricity authority of Lebanon, which do not enter into public budgets from 2018 onwards.

B. How social expenditure compares in the region and with the world

Developing a regional and global comparison of social expenditures required focusing on the HES, since data on other aspects of expenditure are not available or are filtered from published Government finance reports. The HES covers 127 countries, including 14 Arab States. For analysis, countries were grouped by income and development level.

-

1. The size of public budgets as a whole

From 2010 to 2019, public expenditure as a share of GDP remained almost stagnant in the Arab region at around 34.6 per cent, compared to the world average of 35.7 per cent. In 2020, the world average increased to 39.5 per cent during the pandemic.46 The Arab regional average increased to 35.9 per cent but remained lower than global average with most economies facing limited fiscal space and contraction in their incomes.

-

2. The size of HES expenditure in public budget allocations

Based on the HES definition, on average, Arab Governments devote around 8.3 per cent of GDP to social expenditure. This compares to a world average of 19.8 per cent drawn from the latest available data in 2018. Since the regional average for total public expenditure as a share of GDP is almost on par with the global average, the difference in public social expenditures is striking. One explanation is that many Arab countries spend disproportionately on military investments instead of social ones.

-

3. HES expenditure per capita

Social expenditure per capita under the HES definition constituted nearly a quarter of public expenditure per capita in the Arab region in 2018. The regional average was $491 compared to the global average of $2,399. Arab high-income and middle-income countries have significantly lower public social expenditure per capita than global peers.

C. Calculating public social expenditure with the SEM

Calculating total public social expenditure across

the seven SEM dimensions found that it accounts

for between 10-20 per cent of GDP in most

Arab countries. In 2019, the highest-spending

Governments were Iraq and Tunisia, which both

dedicated more than one fifth of GDP to social

expenditure.

Among the seven SEM dimensions, the largest

share, reaching 9.5 per cent of GDP in 2019, went

to social protection, subsidies and support to

farms, based on eight countries with available

data. This dimension has seen the greatest

fluctuation in expenditure over time due to

significant year-to-year changes in the value of

subsidy programmes.

A look at social expenditure by SEM dimension

(a) Education

Education expenditure represented 11 per cent of the region’s total public expenditure and 22 per cent of public social expenditure in 2019. Seventy per cent of education expenditure goes to primary and secondary education. This represents 2.5 per cent of total GDP for the countries assessed with the SEM (figure 7). Information on early childhood expenditure is available in two countries, namely Jordan and Tunisia. However, their share is too little. In 2019, it was 0.35 per cent of education expenditure in Jordan and 0.16 per cent of education expenditure in Tunisia.

Figure 7. The bulk of education spending goes to lower levels

(b) Health and nutrition

Social expenditure on health and nutrition ranged from 1.2 per cent of GDP in Egypt to 2.8 per cent in Oman, making it one of the larger SEM dimensions. In all countries with sufficiently detailed data, inpatient services comprise the largest component of this expenditure (figure 8). which represented roughly one and a half percentage points of GDP

Figure 8. Inpatient hospital services consume a large share of spending on health and nutrition

Note: Tunisia’s expenditures on outpatient and inpatient hospital services are combined due to data limitations, as shown in a different colour pattern than the rest.

(c) Social protection, subsidies and support to farms

Food and energy subsidies and cash and in-kind benefits are responsible for most spending on social protection, subsidies and support to farms in selected countries. As this is the largest of the seven SEM dimensions, subsidies and cash and in-kind benefits represent a significant share of overall public social expenditure. Spending on energy and food-processing subsidies amounted to 5.4 per cent of GDP in 2019, on average, as an aggregate for selected Arab States (figure 9).

Figure 9. Food and energy subsidies are prominent in spending on social protection, subsidies and support to farms

(d) Housing, connectivity and community amenities

Housing is fundamental to education, employment and health in addition to its significant role in citizen identity and social belonging. Social housing policies include all Government policies to increase access to adequate housing, control rents and facilitate access to finance. The SEM shows that spending on housing, connectivity and community amenities is well distributed across various components but their composition has been changing. By 2019, the proportion was 60 per cent or about 1.5 per cent of GDP on average (figure 10).

Figure 10. Housing and community development have seen increasing investment in some countries

(e) Labour market interventions and employment generation

Iraq, Jordan, Oman, and Tunisia all designate social expenditure for labour market interventions and employment generation but through different strategies. In 2019 and 2020, Tunisia increased expenditure on employment generation through public sector employment creation programmes and grants and incentives to promote private enterprises. Training and skills upgrading is a primary focus in both Jordan and Oman. Investment in research on labour market programmes and policies is a substantial area of support in Jordan and, to a lesser extent, Tunisia (figure 11).

Figure 11. Public budgets to support labour markets are marginal in most countries

(f) Environmental protection

Expenditure on environmental protection has not meaningfully increased despite the growing urgency of investment in climate action, biodiversity protection, waste management, and renewable energy. Spending as a share of GDP is low and remained constrained during the last decade, ranging between 0.32 per cent in 2011 and 0.24 per cent in 2019. Few countries increased allocations in 2020 (figure 12).

Figure 12. Overall environmental protection spending is very low and constrained

(g) Art, culture and sports

Tunisia leads in spending on arts, culture and sports as a share of GDP, especially in support to sports and physical education, which aligns with strategic priorities to encourage young people to develop as productive citizens. Jordan’s National Vision 2025 also emphasizes promoting cultural development and cultural industries, especially among youth. Programmes include maintaining archaeological sites and museums and spreading the use of the Arabic language (figure 13).

Figure 13. Arts, culture and sports spending has contracted slightly in several countries

D. Subsidies top social policy expenditure, innovation and investment lag

The Arab region’s often short-term perspective on public social expenditure has undercut investment in human capital and economic transitions. This is evident from a look at the top 10 expenditure categories across the SEM dimensions. A considerable sum goes towards subsidies for energy and food, more than the next two largest spending categories combined. No element of environmental protection or labour market and employment spending makes the top-10 list (figure 14).

Figure 14. The top 10 social expenditures in the Arab region reveal a short-term perspective, 2019

Note: For inpatient and outpatient services, averages omit Lebanon, Tunisia, and Iraq as the budgets do not allow for disaggregation between such expenditures.

E. Who benefits and how much from social expenditure?

To better understand the distribution of social expenditure, the SEM offers an innovation by classifying expenditures across broad categories of beneficiaries, namely, children, young people and adults disaggregated by sex; older persons; persons with disabilities, sickness and survivors; socially marginalized people or those at risk of social exclusion, refugees and immigrants; households benefitting from financial or in-kind support; and the community at large.

1. Support to households and families dominates but is trending down

A large share of social expenditure is classified as targeted at households and families; on average, 16 per cent of GDP and 42 per cent of total social expenditure in 2019. Support to households and families increased from 2011 to 2013, reaching a peak of 14 per cent of GDP, but has since generally trended downwards as the value of subsidy expenditures has declined (figure 15).

Figure 15. On average, a large share of social expenditure is targeted at households and families, although with a downward trend

Note: Weighted average of eight countries, as per data available for the SEM. Multiple population groups are a category where social programmes benefit more than one population category and data are not disaggregated.

2. Varying shares to children, youth and the elderly

Based on the most recent data, education expenditure on youth and adults made up 1 per cent of GDP and 5.5 per cent of social expenditure; a majority of spending went to tertiary education (figure 16).

Figure 16. Breakdown of social expenditure on youth and adults

3. Spending targeted to women is shockingly low

Expenditures on programmes and services targeted

to women are almost non-existent, accounting for

only $10 million in 2019, less than 0.01 per cent of total

social expenditure. Only four of the eight countries

had disaggregated data to show expenditure targeted

specifically towards supporting women. In each of

the last two years, roughly 70 per cent of spending

on women has been related to health and nutrition,

comprising expenditures on reproductive health

care, and other health-related programmes including

combating discrimination against women and genderbased

violence, which inflicts harm on women,

girls, men and boys. Spending on social protection

programmes and labour market programmes

targeting women is relatively low.

In Lebanon, which has a relatively higher share

of expenditures targeted to women than other

countries in the sample, the spending is mainly

through reproductive health care and support

through family and maternity benefits (figure

17).

Figure 17. Breakdown of social expenditure on women

F. Spending choices fall short

The Arab region is lagging on public social expenditure compared to other parts of the world. While data limitations meant that the SEM could only examine eight countries, this still revealed several striking patterns. Social protection, subsidies and support to farms is the largest dimension of social expenditure, followed at a distance by education. Very little spending goes to labour market support; the arts, culture and sports; or environmental protection. Employment generation programmes, incentives for business start-ups, social insurance, early childhood development, and social-related research and development get short shrift in budgets.

3. Do spending choices add up to equity – or stand in the way?

Key messages

Arab countries are generally not spending enough on social sectors. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a mixed impact on the adequacy of social spending by sector. Where data is available, public spending in areas such as health, education and social protection is inadequate compared with established international benchmarks and comparable regions. Governments should urgently protect and expand, where possible, budgetary allocations to the social sector, which are critical for investment in human capital and ensuring an inclusive post- COVID-19 recovery.

Social sector financing in the Arab region depends largely on inequitable financing mechanisms, where the contribution of publicly pooled resources to social sector financing lags behind the global average. Public funding pools should be promoted as the most equitable fundraising mechanism, with an emphasis on progressive and effective tax systems. Private financing mechanisms can also be utilized to complement the drive for improved equity in access and outcomes.

Financing in sectors such as health and education is skewed, thereby reinforcing social and economic inequities. This prevents the realization of basic rights for the poorest and most vulnerable populations. Governments should seek to reallocate their education budgets towards earlier levels of education, specifically early childhood education. In health, preventive care for all diseases should be prioritized.

Distribution of social sector benefits, in terms of access and outcomes, tends to be pro-rich. Government should prioritize the design of social sector policies that aim to benefit poor populations the most, by using research on the services most utilized by vulnerable groups to aid service provision decisions. Focus should be on reducing user fees for essential services across health and education, while innovating social insurance schemes for vulnerable groups.

Over the past two decades, nearly all Arab countries have made significant investments

in improving health and education and reducing poverty. Yet, development gains have

not reached all members of societies. The region is among the most unequal in the

world, with dramatic differences in wealth and well-being.

The SDGs are grounded in equity and equality considerations, with their

explicit call to ask who is benefitting and who is left behind (box 1).

The equity of social expenditure can be assessed in four stages: how revenue is raised,

how it is allocated among sectors, how it is spent within sectors, and how it

contributes

to equitable outcomes (figure 18).

Equality is concerned with all individuals receiving equal treatment regardless of need or any other difference. Inequality at a societal level is often replicated through disparities in access to social services and related social outcomes. Equity denotes fairness and centres on ensuring that all individuals have what they need to succeed. In recognizing that individuals do not all start from the same place, equity requires adjustments to imbalances. Since equity may involve “positive” discrimination against certain groups that were better off prior to an intervention, pursuing it may prove controversial and encounter pushback.

Figure 18. Four stages for assessing the equity of social expenditure

A. Finance must be adequate and reach people furthest behind

From an equity perspective, achieving

efficiency in expenditure entails not just

ensuring that resources produce intended

broad development outcomes, such as

health and education goals, but that they

are intentionally distributed to prioritize

accelerated advances for population groups

furthest behind.

For some Arab countries, publicly provided

education does not extend to the completion

of secondary school, leaving poor households

facing a large financial burden to continue their

children’s education. This means that while the

region does relatively well on its average primary

school completion rate, its average secondary

school completion rate lags almost all regions

except Africa (figure 19).

Figure 19. The region lags almost all other regions in lower secondary school completion, 2019

In the share of overall public expenditure on social protection, subsidies and support to farms that is spent on fuel and electricity subsidies, Jordan has the lowest share; Iraq and Oman the highest. Egypt has also had significant subsidies over the past decade, but often with a regressive nature. This is particularly the case with energy subsidies, where richer households benefit more than the poorest households, for reasons that include greater consumption of the subsidized goods. Of all forms of energy subsidies, those for gasoline, diesel and electricity – the focus of the SEM data – are the most regressive (figure 20).

Figure 20. Spending on fuel and electricity subsidies as a share of the social protection, subsidies and support to farms dimension of the SEM

B. Too often, spending reflects and reinforces inequities

Public social expenditure amounts and choices

influence which services are provided, to which

groups and in which locations. If out-of-pocket

costs are high, making up for shortfalls in public

funds, financing may embed inequities (box 2).

Various indicators for access to health care

reveal inequities within countries, and these

are tied to country classification. Countries were grouped in the following three sets for comparison: low-income countries, middleincome countries, and countries with fragile and conflict affected situations

Direct or out-of-pocket payments for a service are usually at a flat rate without considering the ability to pay. They are the most common form of private financing for social services but directly contradict the principle of equitable financing, where the burden of financing is spread equitably across the population through some form of pooled funding. Out-of-pocket payments mean access is determined by the ability to pay rather than need, a significant barrier especially for poor and disadvantaged groups. An average of 27 per cent of current health expenditure in the Arab region is raised through unpooled out-ofpocked payments; the share is 46 per cent when excluding the GCC countries. This compares poorly against the world average of 18 per cent. Some of the poorest Arab countries have the highest rates of out-of-pocket payments in health, such as the Sudan at a 66 per cent share of current health expenditure. Egypt’s share is 62 per cent.

In social protection, data on benefit incidence allow assessment of whether allocation decisions have improved or worsened equity. A lack of recent data limits analysis reflecting reforms, but available data suggest that benefit incidence is inequitable in every country except Djibouti (figure 21).

Figure 21. Benefit incidence of social assistance by quintile of income distribution

C. Fair or unfair, spending defines development outcomes

Another perspective on equity in public financing considers the results of investment, measured by key indicators of health, education and social protection. This highlights how skewed financing reinforces social and economic inequities, and prevents the realization of basic rights for the poorest and most vulnerable populations. Comparing current health expenditure with maternal mortality shows a correlation between higher expenditure and fewer deaths in Arab countries, for example (figure 22).

Figure 22. Higher per capita current health expenditure correlates with fewer maternal deaths

Social protection outcomes, represented by the poverty headcount rate, are also associated with social spending. Where public spending on social protection as a proportion of GDP is higher, poverty tends to be lower, at poverty headcount rates of $3.20 per day (figure 23).

Figure 23. Greater spending on social protection is associated with lower poverty headcount rates

Note: Data are as of 2017 or the most recent available.

D. Rethink and reform for improving equity, lessening inequality

Better understanding of the value of fiscal equity should prompt a rethink leading to reforms that put equity and the universal realization of rights at the forefront of policy design. Fiscal equity reinforces other core principles such as budgetary adequacy, efficiency and effectiveness. It implies prioritizing adequate allocations, in absolute and proportionate terms, to social sectors and ensuring that budgets are financing services most important to the poorest and most vulnerable populations. Such efforts may be initially controversial but could form the backbone of a new social contract built on justice and human well-being.

4. Making money work efficiently

Key messages

The overall efficiency of social expenditure in the Arab region is lower than the global average. Education, housing and environmental protection are identified as areas where Arab countries have significant inefficiencies that can be improved.

It is vital to assess the efficiency of public social expenditure, so as to minimize wastage and improve investment in development priorities. With greater efficiency, to the level of global benchmarks, Arab countries could spend the same as a share of GDP and either achieve greater human development gains or channel savings into other priorities.

Government effectiveness and control of corruption indicators are stronger predictors of social expenditure efficiency than the size of social expenditures. Countries can be more efficient even without high levels of social expenditure.

It is necessary to improve monitoring and governance of social programmes, and modernize the public transfer system to ensure transparency, provide efficient and quality service delivery, and better target vulnerable populations. Since insufficient data limit performance assessments of the efficiency of public social expenditure, Governments should seek to improve data systems.

The impact and reach of social expenditure vary across countries. Understanding

the degree of efficiency in achieving desired results helps policymakers steer

allocations to sectors and population groups that are most in need and where

returns will be greatest.

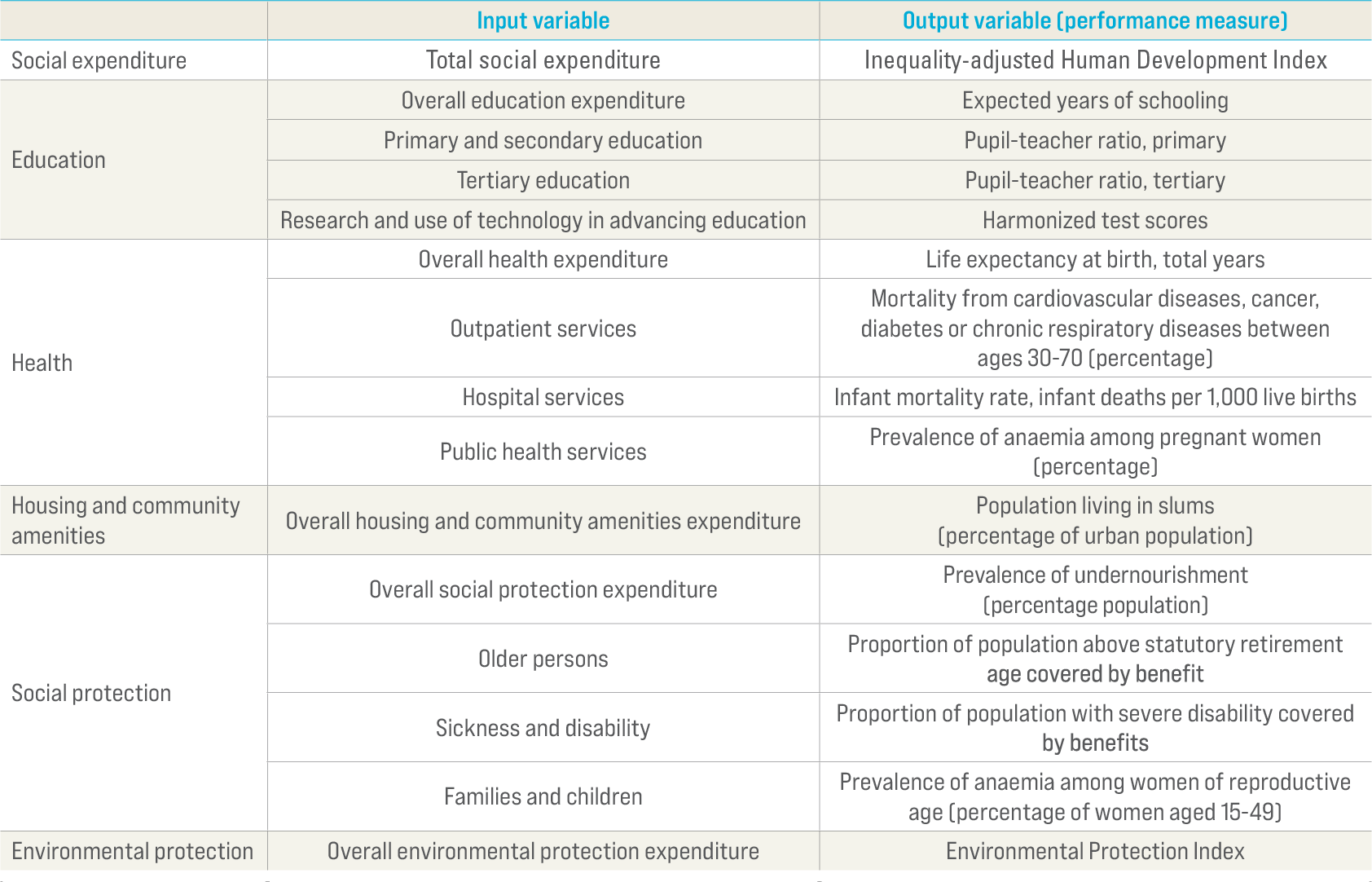

An efficiency analysis of 127 countries globally included 15 from the Arab region,

based on data availability for a set of input and output variables (table 3).

Note: The choice of indicator and its link to an output or outcome are driven partly by conceptual analysis and partly by data coverage. For example, the performance measure of education expenditures relating to the quality of schooling is unfortunately not available or not adequate for such assessments. Therefore, the teacher-pupil ratio was taken as a proxy to indicate that higher public expenditure on education would improve the teacher-pupil ratio, which improves the quality of education in general. Similarly, indicators such as poverty rate, poverty gap and coverage of social protection benefits for children are critical to assess efficiency but lack adequate data. These are discussed in box 5 as a robustness check.

A. How far does expenditure go in achieving social aims?

In broad terms, public social expenditure has a strong positive correlation with the Inequalityadjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) (figures 24a, 24b), which captures advances in education, health and income as well as how evenly achievements are distributed. In the Arab region, human development advances have slowed markedly since the 1990s, partly because incremental progress is harder but also largely because the budget share going to health and education has remained almost stagnant or declined.

Figure 24a. Social spending compared to the Inequality-adjusted human Development Index

Figure 24b. Education spending compared to expected years of schooling

B. Social expenditure efficiency: how the Arab region compares to the world

Looking at specific sectors, in education expenditure, Arab countries are significantly less efficient than the global average. They achieve fewer expected years of schooling than global peers relative to spending levels. Average overall education expenditure efficiency is 0.77 compared to the global mean of 0.84. Considering components of education expenditure, Arab countries fare better, especially on primary and secondary education spending. Regional efficiency here was 0.94 compared to the global mean of 0.92. Efficiency in tertiary education is lower than the global average (figure 25).

Figure 25. Education expenditure efficiency in the region is dragged down by inefficiencies in tertiary education and education research and use of technology

Note: MIC stands for middle-income country; HIC stands for high-income country.

Arab countries are relatively efficient in turning health expenditures into better health outcomes, represented by overall life expectancy. Health expenditure efficiency in Arab countries is 0.89, higher than the global mean of 0.87 (figure 26).

Figure 26. The region’s health expenditure efficiency is higher than the global mean but does not reflect high levels of out-ofpocket spending

Note: MIC stands for middle-income country; HIC stands for high-income country.

C. Contributions to efficiency across and within sectors

Overall efficiency in social expenditure builds on efficiency in different dimensions, such as education, health, social protection, housing, and environmental protection. In turn, efficiency in each sector derives from various components. This is illustrated here through decomposing spending on education, health and social protection, where expenditure subcomponents are available.

Across all countries in the sample, on average, the efficiency of expenditures on social protection, education and health makes significant contributions to the overall efficiency of social expenditure. Social protection is slightly ahead, followed by health and education. Housing and environmental protection do not make a statistically significant contribution.

A decomposition of efficiency at the country level assessed drivers of changes in efficiency at two points of time, a three-year average around 2013 and a three-year average around 2018, for overall as well as education and health expenditures. In the Arab region, only Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia have enough data to track links between changes in the overall efficiency of social expenditure between 2013 and 2018. The most visible positive impacts come from changes in education expenditure efficiency, such as in Egypt and Morocco. The influence of other factors is relatively minor. More research is needed to fully understand how efficiency relates to changes in particular spending components.

D. Context makes a difference

Several factors linked to country context can determine the efficiency of social expenditure. As a starting point, globally, the correlation between overall efficiency and total expenditure as a percentage of GDP is positive although not very strong. In figure 27, a visible cluster of high-efficiency countries in the upper right corner indicates that almost all countries with social expenditures exceeding about 25 per cent of GDP are relatively efficient. The notion that countries with more fiscal space will likely be more efficient is only partially confirmed by data, however. Fiscal space explains only about 9 per cent of overall variation across countries. Even States that cannot afford high levels of social expenditure, due to negative fiscal balance, can be efficient. The State of Palestine is an example, with an overall efficiency score exceeding 97 per cent even as total public social expenditure stands at 4.2 per cent of GDP.

Figure 27. Overall efficiency of social expenditure and social expenditures (percentage of GDP)

Efficiency is weakly associated with sectoral expenditure (figure 28). The most significant association is for social protection, where sector expenditure explained 22 per cent of differences in efficiency scores. There was no significant relationship between fiscal balance and sectoral efficiency. This suggests that factors other than fiscal variables determine efficiency in education, health, social protection, and environmental protection.

Figure 28. Individual sectors show limited correlation between expenditure efficiency and amount, except for social protection

As with overall social expenditure, efficiency at the sectoral level positively correlates with Government effectiveness (figure 29). The relationship is quite strong and similar across education, health, social protection, and environmental protection. Sectoral efficiencies also fall in a narrow range when considering the World Governance Indicator on corruption, again indicating that Government capacity is a more significant determinant of efficiency than the size of spending.

Figure 29. Government effectiveness has a strong association with the efficiency of sectoral expenditure

E. Efficiency and outcome simulations in Jordan and Tunisia

One type of policy simulation involves fixing the output indicator at a predetermined level and assessing the possible combinations of spending and efficiency required to achieve the desired output. This approach was applied to policy simulations using Jordan and Tunisia as examples. Generally, the simulations assessed improvements on SDG indicators if both countries increased social expenditure to global averages and raised efficiency to the average of high-income countries. They also considered potential savings from increasing efficiency alone.

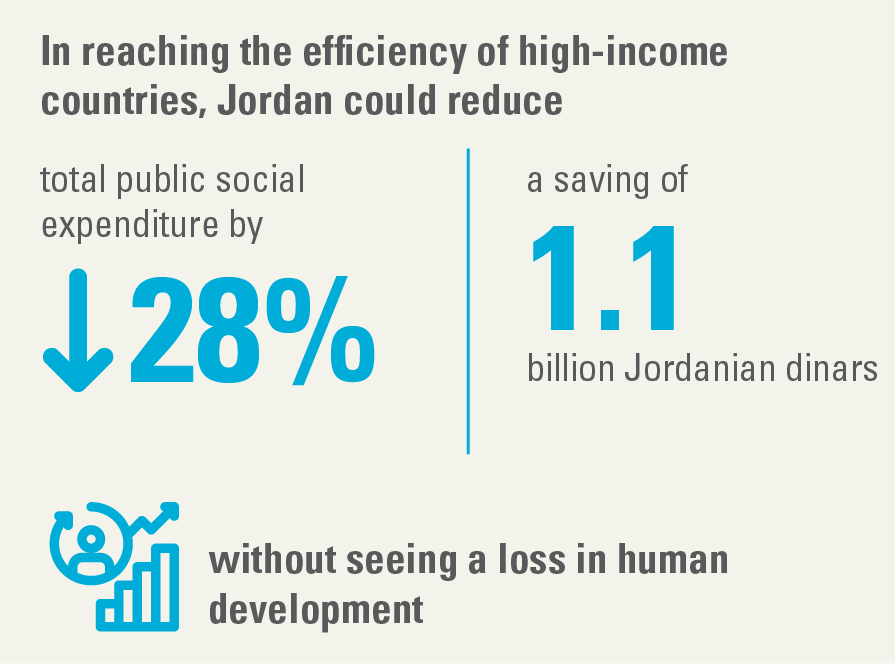

- If Jordan increased overall social expenditure by 24 per cent from current levels to match the global average of 16.6 per cent of GDP, its IHDI score would increase from 0.622 to 0.628.

- If Jordan kept its current level of social expenditure, as a share of GDP, and improved its efficiency to match the average of high-income countries, its score on the index would increase from 0.622 to 0.774.

- In reaching the efficiency of high-income countries, Jordan could reduce total public social expenditure by 28 per cent, a saving of 1.1 billion Jordanian dinars, without seeing a loss in human development.

Jordan:

- If Tunisia holds total social expenditure unchanged and improves its efficiency to match the global average, its score on the IHDI would increase by 34 per cent, from 0.580 to 0.668.

- If the level of social expenditure is raised to the global mean of 16.6 per cent of GDP in combination with improved efficiency, its index score would increase further to 0.675.

- If efficiency meets the global average and Tunisia stays at the same level on the IHDI, it can reduce total public social expenditure by 19 per cent, an annual savings of 3.1 billion Tunisian dinar.

Tunisia:

F. Adequate spending, more efficient choices

The most powerful development outcomes

occur when public social expenditure is both

adequate and efficient. The Arab region has made

investments but without maximizing the returns,

a tendency that countries and their citizens can

no longer afford.

Assessing and

closing efficiency gaps can minimize waste and

ensure that resources reach population groups

and areas of development where needs are

greatest. In doing so, countries can achieve

better outcomes without spending more or

achieve the same outcomes by spending less.

5. Enhancing social expenditure and fiscal sustainability

Key messages

Debt and liquidity challenges are apparent in the region’s inability to effectively respond to the pandemic fallout, let alone jumpstart a resilient recovery. Fiscal stimulus was low during the pandemic, both compared with the global average and given the needs arising from dramatic losses in income and jobs and from strict pandemic containment measures.

Credible fiscal frameworks should be developed over the medium term for revenues and expenditures. Debt relief and innovative financing solutions, such as debt swaps, are critical to enlarge fiscal space in the short term. Fiscal space may also grow by stabilizing debt-to-GDP at a higher rate in the medium term, in line with a requirement for social investments that enhance human capital and GDP.

Improving equity, progressivity and efficiency in revenue mobilization remains a challenge for Arab countries. Average tax-to-GDP for the region has remained at about 8 per cent since 2010. The median tax-to-GDP for Arab middle-income countries is 16 per cent, which is lower than the global averages of developed and middle-income countries.

It is important to improve domestic revenue mobilization by increasing tax collection, reassessing the tax base, enhancing tax equity and progressivity, addressing tax inefficiencies, and controlling illicit financial flows given the scale of tax revenue leakages and abuses, such as tax evasion, trade misinvoicing and tax avoidance. Increasing tax collection should involve investing in quality public services that inspire trust and create buy-in among taxpayers.

A. A decade of pressure on fiscal space

The COVID-19 crisis, coming after a decade of economic and political shocks and downward pressure on growth and Government finances, has widened fiscal deficits and spurred debt growth that in some cases teeters on unsustainability.

1. COVID-19 made economies even more vulnerable

Impacts vary, however, by different subregions and country groups (figure 30). Economies vulnerable before the pandemic became even more so. A moderate rebound in growth in 2021 depended on a global rebound and increased demand for oil and on the reasonable success of vaccination campaigns.

Figure 30. Forecast GDP growth rates vary across country groups, 2020-2023 (Percentage per year)

2. More debt, less liquidity

The region has faced rising public debt since the beginning of the 2010s, putting it in the territory of debt unsustainability. COVID-19 amplified already heavy debt burdens, complicating recovery and social expenditure for several low- and middle-income countries. Debt in the region reached an estimated 60 per cent of GDP in 2020 (equivalent to $1.4 trillion), up from 25 per cent in 2008 (figure 31).

Figure 31. Rapidly escalating public debt has resulted from low growth and inefficient public finance management

Note: The aggregate for the conflict-affected countries excludes the State of Palestine and the Syrian Arab Republic. The aggregate for the least developed countries excludes Somalia and the Sudan.

B. Fiscal strategies for enhancing social expenditure

To secure adequate public finance and meet current needs, many Arab countries will need to turn to domestic revenue mobilization. This may entail improving tax collection, widening the tax base and/or enhancing tax progressivity.

1. Total revenues vary widely across the region

Public revenue as a share of GDP has dropped over time, from a peak of 42 per cent in 2008 to 31 per cent in 2019 (figure 32).

Figure 32. Total revenue in the Arab region and subregions

Note: Regional and subregional aggregates are weighted averages. The averages exclude Somalia, the State of Palestine and the Syrian Arab Republic due to unavailable data. The classification of emerging market and developing economies follows that of the IMF World Economic Outlook.

2. Tax equity and efficiency need to improve

Improving tax revenues remains a challenge for most countries in the region. Total tax revenues in the region as a share of GDP have remained at around 8 per cent since 2010 (figure 33). The share in 2019 ranged from a low of 1 per cent in one oil-exporting country, the United Arab Emirates, to 25 per cent in one oil-importing middle-income country, Tunisia.

Figure 33. Improving tax revenues remains a challenge given a relatively stagnant share of GDP

Outside Algeria and Morocco, most Arab countries still suffer from low tax buoyancy as GDP growth does not trigger a proportional rise in tax revenues. Weak tax administration and leakages explain this performance. While it is typical in settings where large parts of the economy are informal, much of the tax loss comes from high-net-worth individuals and hardto- tax professional services (figure 34).

Figure 34. Most Arab countries suffer low tax buoyancy

Note: Percentage increase in tax revenue per 1 per cent increase in GDP.

3. Official development assistance commitments must be met

ODA is critical in realizing several SDG targets. The ODA to Arab countries has steadily increased since 2011, following sharp declines during 2008- 2010. In 2019, total ODA to the region was $33.9 billion, approximately 10 per cent below 2018, the peak within the past decade. Of the ODA provided by all sources to developing countries in 2019, 17.6 per cent went to Arab States.

Increasing ODA to the region is largely influenced by in-country “refugee” costs and humanitarian aid (figure 35). About 90 per cent of ODA to the Syrian Arab Republic in 2019 was humanitarian aid. Among the least developed countries, Somalia and Yemen received a higher ODA inflow in the past five years, largely from humanitarian aid. In contrast, ODA to the Sudan declined significantly. Flows to middleincome countries, including Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia, appear to have increased during the past decade but remained volatile, fluctuating year to year.

Figure 35. Increasing ODA to the region largely goes to humanitarian aid (Percentage)

C. One way forward: modelling debt stabilization in Tunisia

The following case study of Tunisia demonstrates how debt stabilization works. It applied a structural macroeconomic modelling and forecasting framework, based on the World Economic Forecasting Model, to assess the impact on macroeconomic performance.173 While Tunisia is a leader among Arab middle-income countries in increasing taxes as a share of GDP and has potential to improve tax collection, it still suffers from underlying inefficiencies and leakages. Debt financing through stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio is also a viable option.

Scenario 1

Stabilizing debt at about 85 per cent until 2030, instead of reducing it to 78 per cent as implied in the baseline scenario, can generate additional fiscal space for government expenditure of 21.2 billion TD from 2022 to 2030. This scenario would push government expenditure above the baseline from 2025 onwards. GDP growth would be above the baseline by 0.2-0.4 per cent from 2025 onwards, with output higher than the baseline starting from 2025. Additional nominal GDP generated between 2022 and 2030 would amount to 14.1 billion TD.

Scenario 2

An alternative scenario entails improving fiscal space through debt financing and domestic resource mobilization, namely, by raising taxes by 1 per cent of GDP. This would generate an additional 40.7 billion TD in fiscal space between 2022 and 2030, which is more than Scenario 1. Higher GDP growth in the first half of the projection interval would yield slightly better results in terms of output (nominal GDP) and private consumption. The current account would see a slight deterioration while the primary balance would be close to that of the debt financing solution in Scenario 1.

Scenario 3

Two additional modifications to Scenario 2 produce a third scenario. The two modifications comprise additional fiscal space of 40.7 billion TD allocated specifically to social sectors such as education, health and housing according to their relative shares within total social spending, and a phased-in increase in total factor productivity of 4 per cent by 2030. Monetary policy intervention would be delayed, minimizing the adverse impact on the demand side. Additional fiscal space for government expenditure under Scenario 3 would amount to 42.2 billion TD from 2022 to 2030, an 8.3 per cent increase above the baseline, which compares to 8.0 per cent in Scenario 2 and 4.1 per cent in Scenario 1.

D. Managing for the future

One key to plugging gaps in fiscal stimulus

packages for recovery and the SDGs is for

developed countries to fulfil ODA commitments

and climate pledges. Another is for IMF member

States to channel unused Special Drawing Rights

from advanced to developing countries based on

indicators of vulnerabilities and needs, including in

terms of trade and balance of payments imbalances,

crises and financial shortfalls stalling recovery.

Innovative financing instruments such as debt

swaps should be used to alleviate mounting

pressures on public finance and release funds for

the SDGs.

6. Managing public finances to achieve social goals

Key messages

Public financial management (PFM) extends to all aspects of managing public resources. It informs policymaking and provides instruments for its implementation. Strong PFM enables sustainable development and inclusive growth through reliable and well-executed budgets, greater spending efficiency, and allocative effectiveness. Because of weaknesses in PFM systems, Arab countries are at risk of misguided fiscal policy decisions and derailed implementation plans in achieving the SDGs.

PFM reform is a pressing priority for Arab countries to progressively tackle PFM system bottlenecks in accordance with a roadmap that factors in country specificities, including the strengths and weaknesses of existing systems and national resources and capacities, noting that core PFM functions should be prioritized.

The management of assets and liabilities, accounting and reporting, and external scrutiny and audits are generally weak in the Arab region. There are also gaps on performance indicators related to budget reliability, the transparency of public finances, and policy-based fiscal budgeting. Weaknesses specific to countries with fragile and conflict-affected situations centre on payment controls and insufficient procurement mechanisms.

Key areas for PFM reform in the Arab region to enhance the management of investments in social sectors, budget execution, transparency, and oversight and accountability mechanisms depend on the country context, but generally include quality and timeliness of management and financial reporting, budget transparency and medium-term frameworks, debt and investment management processes, internal audits, role of the legislature, and independence of supreme audit institutions.

A. PFM steers social spending in the right directions

PFM makes fiscal policy operational. It extends to all aspects of managing public resources, including raising taxes and other revenues, and managing expenditure, debt, cash, and fiscal risks. It supports reporting and monitoring. A key aspect of strong PFM is its medium-term budget framework, which offers “a natural institutional arrangement for prioritizing, sequencing, planning, and managing revenue and expenditure over a rolling period of three-to-five years”. Since a budget is a Government’s primary fiscal policy document, it is central to PFM.

B. A challenging region for reforms

1.

PFM systems reflect their context. Fragility and corruption typically undermine them, issues at work in many Arab States. Transparency International’s 2020 Corruption Perception Index found that the oil-exporting countries are generally perceived to be the least corrupt in the region, followed by the middle-income countries and lastly by countries with fragile and conflictaffected situations, which rank as among the most corrupt countries globally.

2.

High debt levels, fiscal deficits and lagging social outcomes also create challenging environments for PFM. COVID-19 hit at a time when most Arab countries were facing strenuous fiscal circumstances. By the end of 2019, except for Iraq and Mauritania, countries with fragile and conflict-affected situations, middle-income countries and four out of the seven oil-exporting countries (Algeria, Bahrain, Oman, and Saudi Arabia) had fiscal deficits, which have grown worse during the pandemic.

3.

Even before the pandemic, the Arab region was grappling with economic and gender inequality, youth unemployment and refugee movements, and had fallen behind on health and education outcomes. As a result, several Arab States launched efforts to create fiscal space for social spending. These included tax reforms (Mauritania), efforts to enhance tax administration and rationalize tax exemptions (Djibouti and Morocco), attempts to mobilize and diversify revenues (Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates), and the better targeting of social safety net spending.

4.

Significant budget deviations in terms of actual and estimated expenditures in social spending are a critical issue. In 2019, examples of large social expenditure variances, where spending does not always reflect the amounts originally approved, included 16 per cent for education in Lebanon; about 9 per cent and 12 per cent for health in Tunisia and Jordan, respectively; and about 33 per cent for environmental protection in Jordan and Tunisia. These figures speak to the weak reliability of social expenditure budgets either because budgets are not realistic or are not implemented as intended.

C. Breaking down the shortfalls in PFM performance

An annual budget law is the ultimate expression

of a Government’s political, economic,

social, and other development priorities. The

budget is a fundamental tool for planning,

risk management, authorizing expenditure,

assessing performance, communicating,

transparency, and accountability (figure 36).

Within the budget cycle, the Public Expenditure

and Financial Accountability (PEFA) framework is

the most common comprehensive diagnostic of

PFM quality. It identifies the following seven core

components: budget reliability, the transparency of

public finances, management of assets and liabilities,

policy-based fiscal strategy, budgeting predictability

and control in budget execution, accounting and

reporting, and external scrutiny and audit. These

pillars are disaggregated into 31 indicators and 94

dimensions to assess PFM performance.

Figure 36. The key stages of the budget cycle

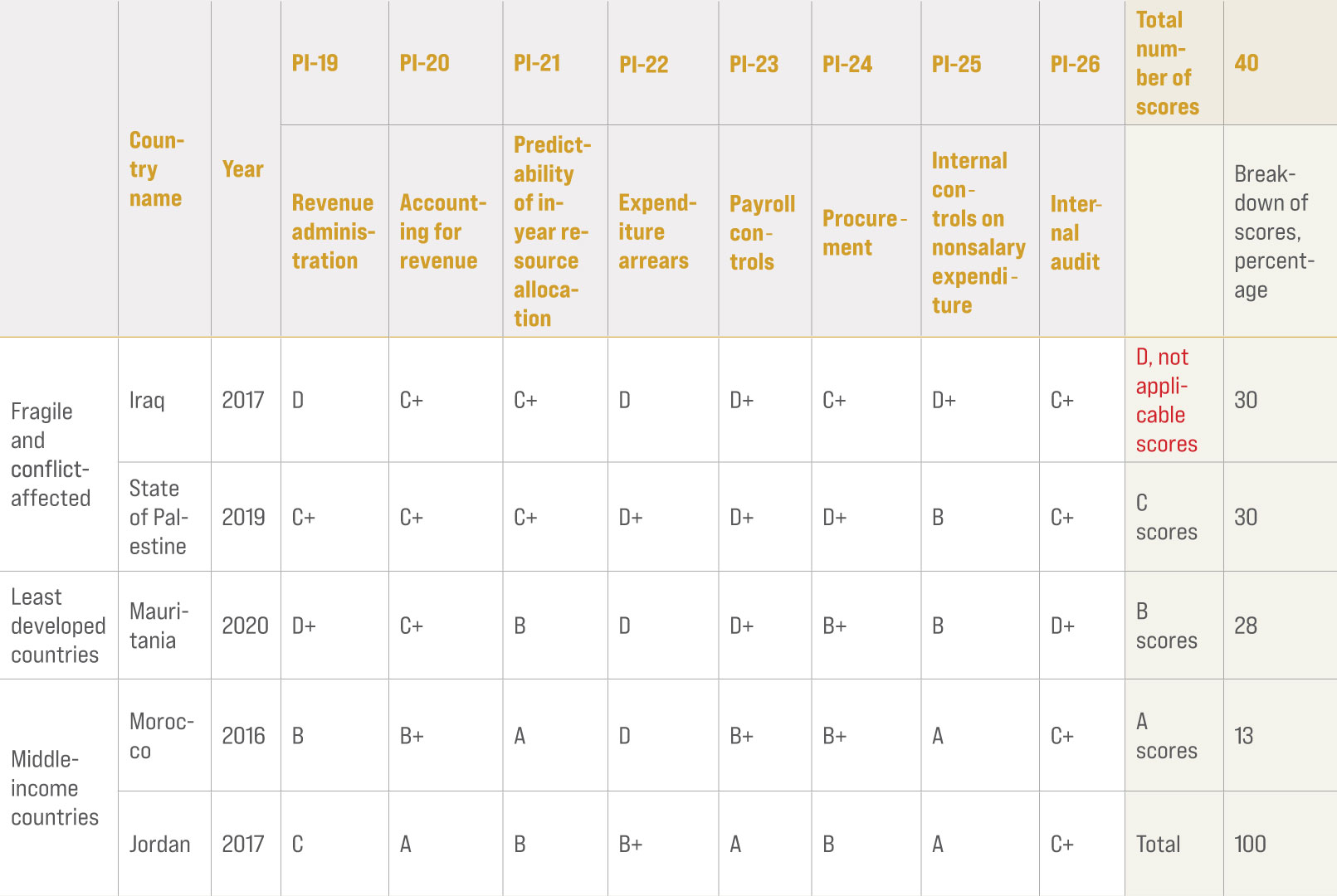

D. Significantly weak PFM system components show multiple points of poor performance

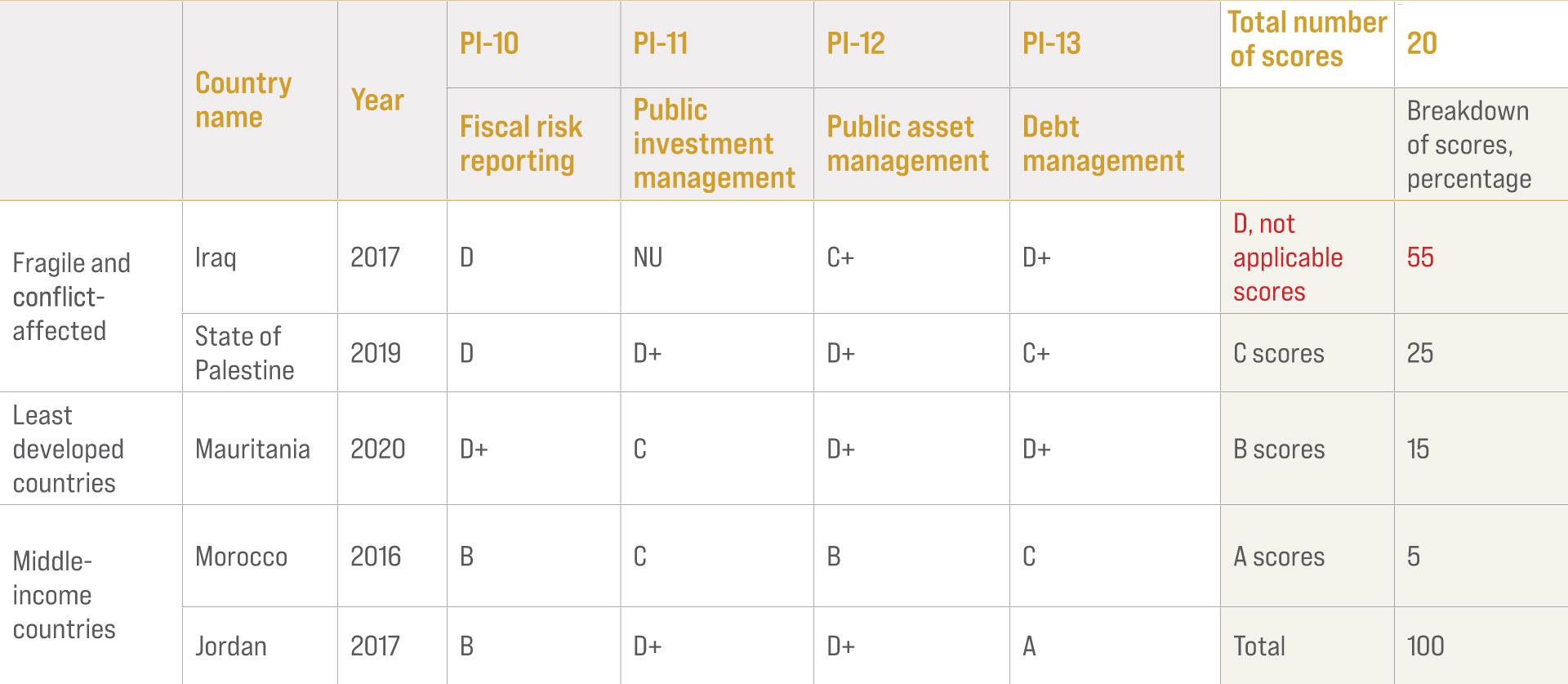

Management of assets and liabilities, Pillar III

Within PEFA Pillar III, on management of assets and liabilities, public investment management appears to be a major challenge, primarily due to weaknesses in investment project costing (table 3). Only two of the five countries assessed meet basic levels of performance, however, while two out of five do not. For the fifth country, this indicator was not used.

Table 3. Pillar III PEFA scores

E. Weak PFM components have gaps on some indicators

Transparency of public finances, Pillar II

Public access to comprehensive fiscal information

undermines transparency in the 2016 framework

assessments.

Fully transparent budgets are an important

stride towards mending social contracts

and inclusive public participation, which

is associated with effective public service

delivery, increased willingness to pay taxes,

enhanced oversight, and better accountability.

Higher transparency correlates with enhanced

PFM through lower deficits, borrowing costs,

perceived corruption and inequality, among

other factors, along with improved tax

collection, resource allocation and accounting,

all of which support development more broadly.

A simple way to enhance transparency is to

publish documents in a timely manner. The

Sudan’s 2018 approved budget was published

online almost 11 months after its enactment,

rendering it of little value in terms of public

oversight or participation. Producing but not

publicly sharing documents is unfortunately a

common practice in the Arab region (table 4).

Table 4. The Arab region has the world’s smallest share of publicly available documents

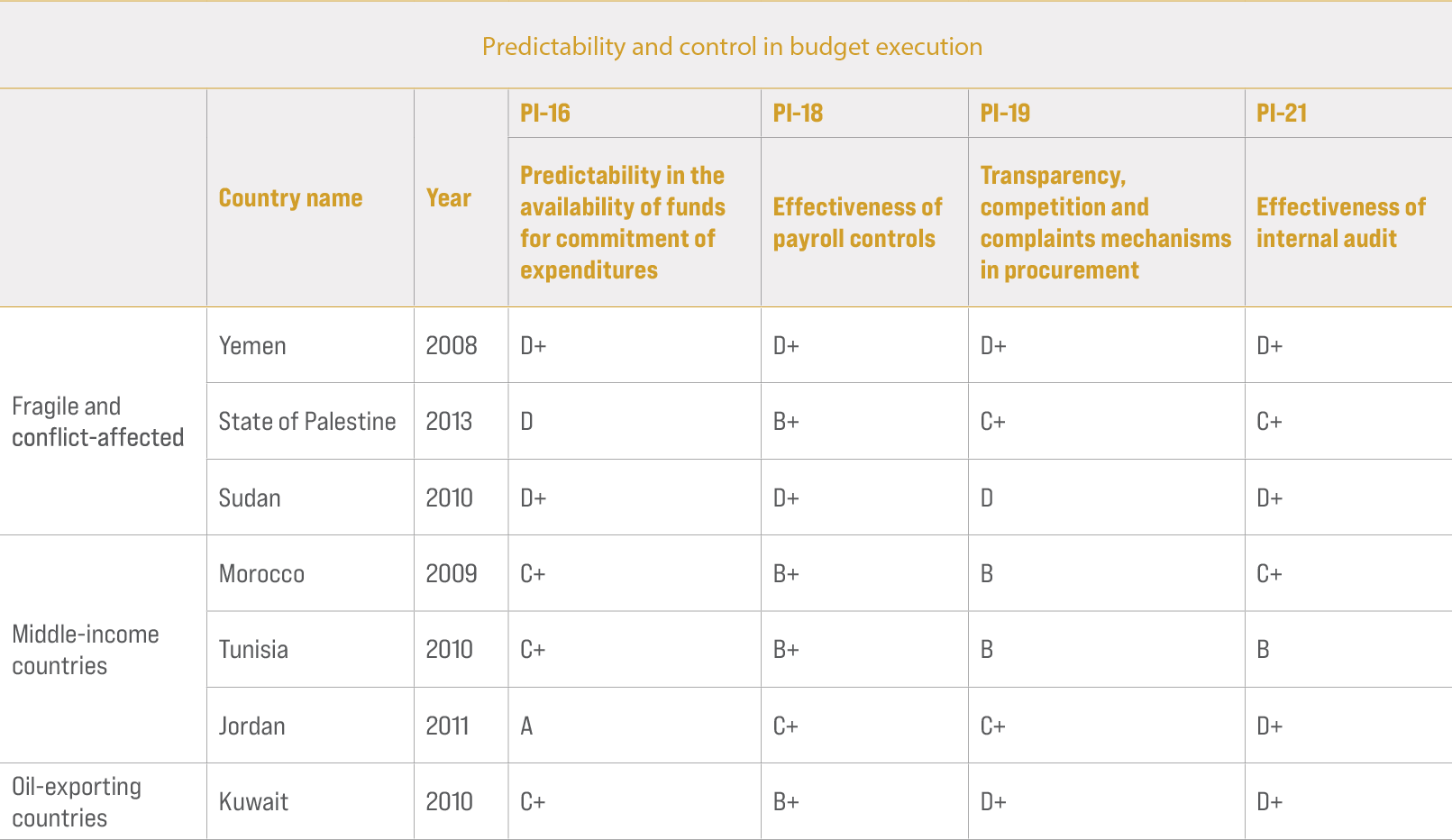

F. PFM weaknesses specific to countries with fragile and conflict-affected situations

In the 2011 and 2016 framework assessments (table 5 and table 6), Iraq, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, and Yemen, all with fragile and conflictaffected situations, scored “D+” on payroll controls. This means that they generally do not achieve basic performance in managing public wages, maintaining the consistency of personnel records and handling changes. The Sudan has no reportage of direct linkages between personnel records and payroll data, and payroll changes are not implemented promptly. There have not been any payroll audits for the past couple of years. Control weaknesses are generally fertile grounds for error, waste, fraud, and corruption.

In the public sector, payroll costs are typically material, and therefore strong internal controls provide reasonable assurance that these large sums of public money are spent effectively and efficiently, in compliance with applicable laws and authorizations. This prevents unwarranted growth in the wage bill, unmet payroll obligations, payments to ghost employees, and others. In contrast, weak payroll controls adversely impact efficiency, effectiveness, budget execution, and budgetary outcomes.

G. Steps towards greater inclusion and gender-responsive budgeting through PFM

While the Arab States face numerous challenges in PFM, social spending and the dynamics between them, there have been some efforts to use PFM instruments to enhance social spending that supports inclusive development. One example is gender-responsive budgeting. It seeks to bring gender concerns into public policymaking and implementation by evaluating the different effects of public expenditure and revenue policies on men and women, and the ensuing impacts on gender equality.

The Arab region in general lacks important practices that would take it to a more robust application of gender-responsive budgeting, such as through gender audits, gender provisions in public finance and budget laws and expost gender impact assessments of budget expenditures. But some countries have moved forward, to varying degrees, on three stages of gender-responsive PFM. These include building awareness and knowledge, transitioning from analysis to allocations and mainstreaming to make budgetary systems gender-responsive.

Looking forward, the SEM could provide a valuable tool to enhance gender-responsive budgeting, helping to define and rationalize public expenditures most likely to realize gender equality. The SEM can be part of evaluating gender-differentiated impacts of policy choices, advocating for more and better sex-disaggregated data, tracking the alignment of expenditures with gender objectives and scrutinizing their impacts on actual advances.

Since 2012, Jordan has required accounts of expenditures benefiting children. Child-related allocations in the budgets of key ministries, particularly those pertaining to social sectors, are reported in the main budget law. Child allocations per se do not necessarily respond to all children’s needs, however. Maximizing the benefits for children requires targeting spending to improve equity, inclusion and outcomes such as advances in learning.

H. A roadmap to PFM reform is more vital than ever

The policy reform path for the Arab region is a daunting one. It must continue to manage the pandemic recovery as an immediate priority and chart a course towards well-prioritized and more effective and efficient social spending to achieve the SDGs. PFM systems are fundamental in ensuring that sound systems and processes support informed decision-making.

A published, well-designed reform plan should establish a sequencing process that factors in the strengths and weaknesses of existing systems, resources and capacity constraints, as well as the interdependence between policy design and implementation. No “one-size-fitsall” approach works. But three important points can guide reforms.

1.

First, the plan should refer to the theory of constraints, an approach that identifies the most significant bottleneck in the system, alleviates it and then moves on to the next most significant bottleneck. This is appropriate for PFM systems given their interrelated components. For example, there is little point in enhancing the external audit function as an added layer of control if the original system of operations and controls is impaired. An effective external audit function would certainly pick up on the problems but cannot fix them.

2.

Second, core PFM functions should generally be prioritized. These focus on financial compliance (for example, for revenues, expenditures, assets, and liabilities), fiscal control (such as to ensure compliance with laws and regulations) and budget reliability. Operationalizing these functions lays the groundwork for all other PFM functions and reforms because they ensure that the Government can adopt a reliable plan and stick to it. After these core functions are in place, consideration may be given to more advanced reforms and innovative practices such as climate, gender-responsive and SDG budgeting.

3.

Third, huge benefits may come from working collectively and coordinating efforts across the Arab States. Cooperation generates opportunities for learning and sharing experiences, saving time and effort, and avoiding the mistakes of learning singlehandedly. Coordination reinforces efforts and awareness. For instance, if the entire Arab region decides to adopt accrual-based IPSAS, training centres, programmes and costs could be shared, needed skillsets would develop faster, and the comparability of financial reporting across the region would improve alongside stock market efficiency and liquidity.

In conclusion, given multiple shocks and levels of vulnerability in the Arab region, it is more vital than ever to have solid PFM systems. They can ensure that budgets efficiently contribute to SDG achievement and help prepare for future shocks in a time of fiscal constraints and increasing debt.

7. An agenda for equipping budgets to achieve the SDGs

The following 11-point agenda for action offers some general starting points that can be tailored to specific national circumstances. It calls for Governments to take the lead but also for international support to help strengthen capacities and develop tools to enhance fiscal space for social expenditures. Civil society has a critical role in deepening research on social expenditure equity, efficiency and effectiveness; conducting social policy evaluations; and recommending ways to improve policy choices and outcomes.

Governments need to consider a balanced mix of expenditures. In many cases, this will involve increasing public transfers to targeted social protection programmes addressing poverty and vulnerabilities and investing in improved human capital and economic growth. There are two main priorities.

- First, several social policy areas have remained at the margins of public budgets, such as expanding capacities among youth, particularly through art and sports, and increasing research and development. Labour market support is also limited, such as through employment generation programmes, incentives for start-ups, support to small and medium enterprises, and female employment. Another concern entails building resilience among the most vulnerable, including through early childhood development and social insurance for informal workers. Environmental protection programmes receive short shrift. In each of these areas, budget expenditure is less than 1 per cent of GDP, which severely undermines the effectiveness of public programmes. It often leaves poor and middle-class people at the mercy of costly private-sector service providers.

- Second, better targeting of social protection expenditures improves effectiveness and can save resources that can be redirected to marginalized areas of social policy. Social protection expenditures comprise up to 16 per cent of GDP in some countries but largely entail inefficient and often unfair subsidies for fuel and electricity. Rationalizing subsidies can potentially free resources although should be done carefully. Subsidy reforms mainly for fiscal consolidation could have a contractionary effect on growth and an adverse impact on social development.

As a general principle, reducing social expenditure and thereby diminishing the quantity and quality of public services can have adverse impacts on tax collection since it tends to break the social contract between States and citizens. In contrast, more effective social expenditure policy tends to draw in more tax revenues, based on global experiences.

The effectiveness of social expenditure depends

on how well each unit of expenditure increases

social welfare in the short term and adds to

economic growth in the long term. This requires

improving and sustaining quality public

services and quality infrastructure that catalyse

the mobility of people and the workforce. It

calls for evidence-based monitoring of social

expenditures, policy impact evaluations and

assessments of the economic growth multiplier

effects of social expenditures. Without the insights

gained from these exercises, critical challenges

are often ignored.

For instance, cash transfers or public in-kind

transfers have a short-run effect in stimulating demand in the economy, in addition to protecting

the poor and the vulnerable. These expenditures

should not replace investments in human capital

that deliver a long-run return by creating a quality

labour force and enhancing productivity, however.

An average of 80 per cent of social expenditure

in the Arab region goes to current expenditures,

mainly wages, salaries and public transfers, while

only 20 per cent goes to capital expenditures.

While rebalancing expenditures requires structural

reforms in Arab economies, Governments also

need to better balance spending to support shortterm

needs while making social investments that

generate long-term growth.

Many Arab countries lack comprehensive monitoring of their expenditures on social programmes, which is an obstacle to understanding how well budget choices contribute to the SDGs. Without quality monitoring, public social expenditure often results in inefficiencies such as allocations to multiple and overlapping programmes or mismatches between expenditures and needs. The SEM can help fill the monitoring gap since it comprises more than 50 indicators in seven dimensions aligned with the SDGs. It goes beyond the traditional emphasis on health, education and social protection to capture social policy areas that are essential, such as the labour market housing and connectivity, arts and sports, and environmental protection, but that remain on the margins of most public budgets.

Arab States have devoted important social

expenditures to expanding access to education

and health care. Yet, these gains have not reached

all members of Arab societies, leaving barriers to

equity. Governments need to allocate resources

towards services most frequently used by poor and

vulnerable populations. This is essential not only to

improve development outcomes but also to realize

human rights and uphold social justice.

Some issues arise from inadequate social

expenditure, particularly when it short-changes public

services for the poor and the most vulnerable. A low

share of GDP for spending on health and education

in the Arab region, compared to international

benchmarks, is likely a barrier to equity.

Beyond spending, accurate data on beneficiaries

of public expenditure need to improve to better

analyse equity. Existing information suggests that households and families benefit from public

transfers but it is not clear how equitably distributed

these are. One obviously regressive pattern is when

significant spending goes towards subsidies used

primarily by richer households.

Other discrepancies are evident in marginal shares of public expenditures for programmes targeted to women, at 0.1 per cent of GDP on average for the selected countries in the SEM, and specific vulnerable populations (including people living with disabilities, refugees and immigrants), at 0.2 per cent of GDP. Limited coverage of services for children, a lack of social security for workers in the informal sector and insufficient social security for older people not in the formal pension system are other critical shortfalls in targeting public expenditures.

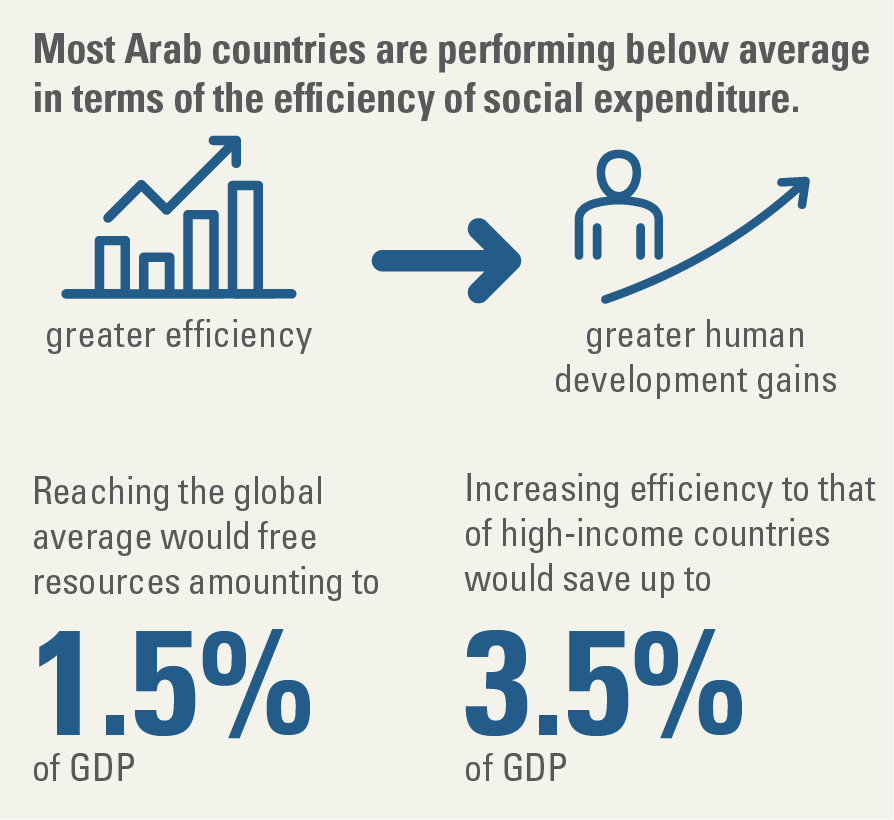

Most Arab countries are performing below

average in terms of the efficiency of social

expenditure. With greater efficiency, to

the level of global benchmarks, they could

spend the same as a share of GDP and either

achieve greater human development gains or

channel savings into other priorities. Reaching

the global average would free resources

amounting to as much as 1.5 per cent of GDP.

Increasing efficiency to that of high-income

countries would save up to 3.5 per cent of GDP.

In education, for example, low efficiency

means that Arab countries reach fewer

expected years of education than global peers

relative to spending levels. Jordan’s overall

efficiency in education expenditure is 0.76

compared to the top-performing high-income

countries at 0.93. Improved education spending

efficiency to meet the high-income country

level would boost Jordan’s expected years of

schooling from 11.5 to 12.1 years.

Many Arab countries are relatively efficient

in public social protection expenditure as

measured by reducing the undernourishment

rate. In reducing poverty, however, inadequate

social protection spending, outside subsidies,

coupled with inefficient targeting to the

poorest and most vulnerable, remain major

challenges. Low public social expenditures

on health, housing and environmental

protection force people to rely on out-of-pocket

expenditures and private service providers,

with adverse implications for equity and