Inequality in the Arab region:

A ticking time bomb

Foreword

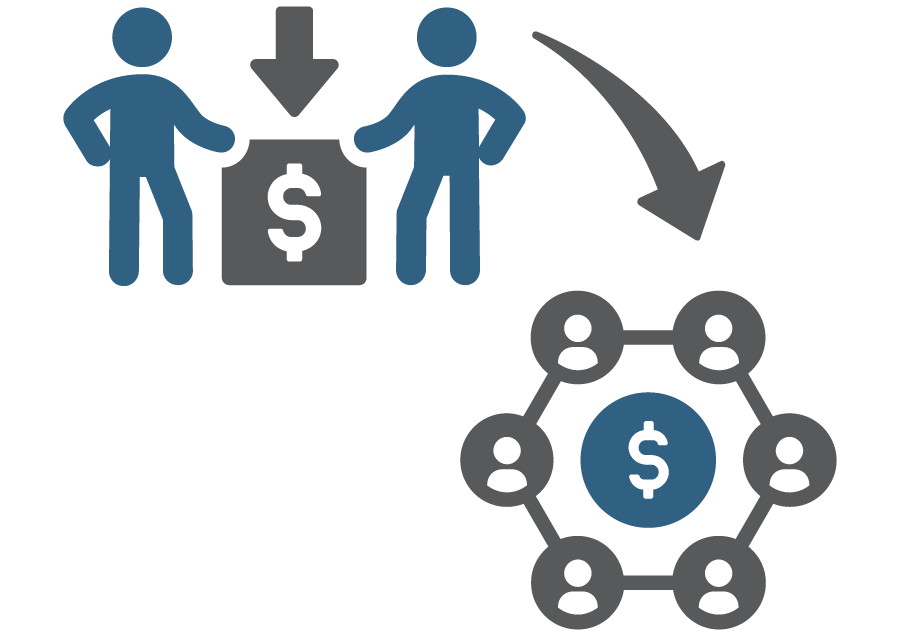

The Arab region continues to be one of the most unequal regions worldwide. As poverty rises, the growing wealth gap between individuals fuels increasing inequality. The region exhibits persistent and increasing levels of inequality in opportunity, especially among certain groups and in certain areas. For example, youth unemployment, which is 3.8 times higher than that of adult workers, has been the highest in the world for the past 25 years. Unemployment among certain groups, such as women and persons with disabilities, is even higher than that of men and persons without disabilities. Gender-based inequalities stubbornly remain above global levels. Wealth creation opportunities are declining, with the wealthiest 10 per cent of Arab adults holding 80 per cent of the total regional wealth. Such factors, if left unaddressed, will deepen existing inequalities, hitting the poorest and most vulnerable communities hardest. These factors risk inflaming greater disaffection and alienation among Arab populations, resulting in a breakdown of social cohesion. Furthermore, social, political and economic inequalities have amplified the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately affected young people in the Arab region. The pandemic highlighted the economic inequalities and fragile social safety nets in the region, with vulnerable and at-risk communities bearing the brunt of the pandemic’s repercussions. Despite this bleak picture, Arab populations are optimistic and hopeful. A survey conducted by ESCWA found that 52 per cent of people in the region believe that equality exists, either fully or partially, while 47 per cent believe that equality will increase in the next five years. This optimism must be utilized. To seize this momentum, Arab Governments should not spare an effort to capitalize on youth enthusiasm, which can serve as a strong catalyst for change. This requires going beyond superficial and temporary fixes to fundamentally reform the root causes of inequality, including addressing structural challenges, corruption, governance and institutional deficits, and introducing coordinated economic and social policies. Notably, creating job opportunities was chief among the demands of those surveyed. Decent job creation is necessary to unleash the productive potential of young people, and avoid another “lost generation” with limited access to opportunities as it transitions into the labour market. Arab Governments must recognize that delivering visible impact, securing credibility, and promoting solidarity within the region constitute a successful three-pronged policy approach to reducing inequalities. Practical solutions should be put in place to translate this approach into practice, and ensure that benefits trickle down to those most in need. To kickstart this paradigm shift in policy reform, I propose establishing a solidarity fund and a regional coalition to reconnect different population groups across the wealthiest and poorest segments of society, so as to create opportunities to ensure dignified and prosperous lives for the poor and vulnerable, improve shared wellbeing, guarantee growth to build stronger and more stable societies that leave no one behind in the achievement of the SDGs, and promote shared responsibilities, societal solidarity and effective partnerships for development. We need to act now. Our children will never forgive us if the legacy they inherit is fragmented, fragile and marginalized societies.

Rola Dashti, Executive Secretary UNESCWA

About the authors

Mehrinaz Elawady

Director, ESCWA Cluster on Gender Justice, Population and Inclusive Development

Introduction

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Arab region has witnessed disparities that sharply contradict the vision of equality and inclusion inspired by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Many poor people in several Arab countries could not procure private medical care and consequently died of the virus, while others survived because they could protect themselves at home or access private health care. Around 8.8 million people became newly unemployed during the pandemic in the Arab region, while the wealthiest 10 per cent of the region’s population now control 81 per cent of its net wealth compared with 75 per cent prior to the pandemic. In 2023, an additional 10.9 million poor people in the region will fall into extreme poverty, 8.5 million owing to the impact of the pandemic and 2.4 million as a result of the war in Ukraine.

The present report builds on the increasing awareness among Governments and people of the importance of tackling inequality as a prerequisite for a just and peaceful society. It complements the Pathfinders flagship global report entitled From Rhetoric to Action: Delivering Equality and Inclusion.

“Inequality and exclusion are not destiny – change is possible.”

Pathfinders, From Rhetoric to Action – Delivering Equality and Inclusion, 2021.

- People globally are demanding a new social contract to heal a divided world. Opinion surveys show an immense preoccupation with societal divisions and a consensus that more needs to be done to address them.

- Nationally, countries that have sustained progress in tackling inequality have adopted the following three-pronged approach:

- ⮚ Delivering visible results that make a difference in people’s daily lives, in areas such as social protection, housing and wages.

- ⮚ Building solidarity through truth-telling exercises and strong community-based programmes.

- ⮚ Securing credibility and avoiding setbacks by fighting corruption and widening political power.

- International policies are a critical complement to national action. The three urgent priorities now are vaccine equity, access to finance, and tax norms and agreements incentivizing those who have most profited from growth to contribute to the COVID-19 recovery and to climate change.

- It lays out key statistics explaining how reducing inequality and exclusion is in everyone’s interest, through more stable growth, pandemic containment, the ability to address the climate crisis, and political stability.

- It looks at the “how to” of practical policymaking, starting with political and practical viability. It describes a menu of 21 policy areas that can be adapted to country circumstances, rooted in polling, research, and government and civil society consultations.

- It combines attention to both income and identity-based inequalities, including gender, race and ethnicity.

- It links the economic and social aspects of inequality to its civil and political aspects, including the links between State capture and inequality, and the benefits of maintaining civic space.

- It is explicit about the relationship between national and international policies in combating inequality and exclusion.

The present report also tackles the long-standing challenge of youth unemployment in the Arab region, which is one of the most enduring forms of inequality. Enhancing the status of young people and assimilating them into the labour market is crucial to reducing inequality, since young people (aged 15-29) represent about 30 per cent of the entire Arab population.