The COVID-19 Pandemic in the Arab Region

An Opportunity to Reform Social Protection Systems

Executive Summary

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, social protection

systems in the Arab region were weak, fragmented, not

inclusive and non-transparent. They were also costly and

unsustainable. Underinvestment in these systems and

exclusion of vulnerable populations were key challenges.

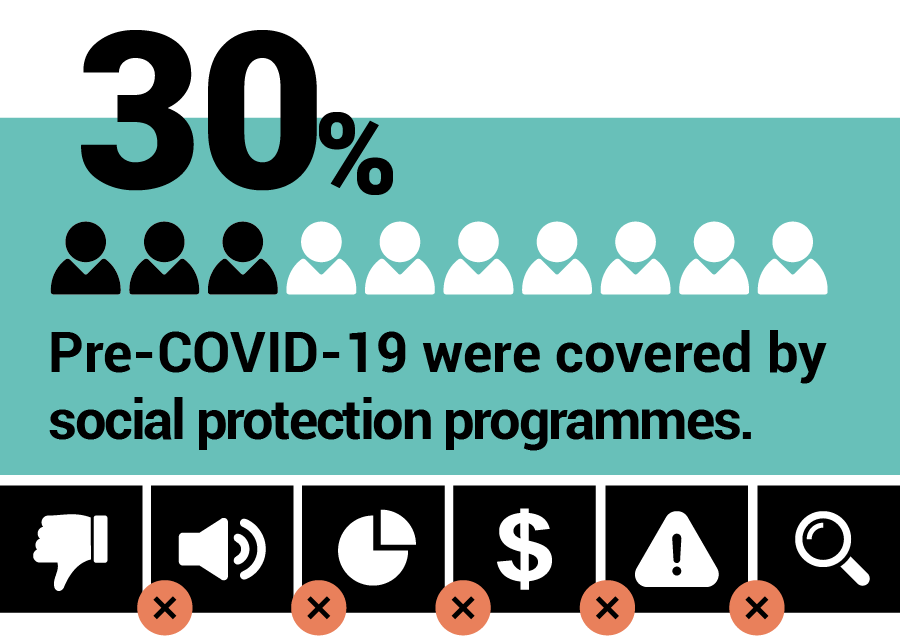

Less than 30 per cent of the population in the Arab region

were covered by social protection programmes.

Most social protection systems were funded through Government budgets or external assistance and not through contributions from beneficiaries or employers. The COVID-19 crisis spotlighted the problems of the social contract between people and Governments and presented a historic opportunity to address some of the challenges facing social protection systems. Lessons learned in various countries were identified as useful examples for change, in addition to certain innovations.

The Arab region witnessed a policy shift from targeting only the poorest population to also including the “missing middle”, such as informal workers who often did not receive any social protection benefits prior to the pandemic because they were not deemed eligible (for example Egypt, Jordan and Morocco). This shed light on the extent to which this group of workers was neglected pre-COVID-19 and the connected structural challenges.

Arab countries excelled in using innovative technologies for the delivery of social protection programmes, especially cash transfers that were delivered to beneficiaries in just a few days through newly created outlets, e-wallets and digital registration. The unique constraints imposed by COVID-19 inspired innovations in the design and delivery of education, health and social protection, which not only protected access to services under extraordinarily challenging conditions, but also facilitated more inclusive outreach.

In many Arab countries, the pandemic accelerated stronger partnerships and greater collaboration between different stakeholders. This was especially demonstrated, among others, through collaborations between different governmental parties at the national level, the sharing/using of databases of beneficiaries (civil registry, vital statistics, tax and social insurance database) and e-platforms such as Government-to-Government (G2G) sites in Egypt.

1. Social protection systems in the Arab region:

context and conceptual framework

Introduction

The Middle East is the most unequal region in the world, with the richest 10 per cent and 1 per cent of the population, accounting for more than 60 per cent and 25 per cent of total regional income in 2016, respectively .

Despite significant improvements in the extension of social protection coverage in the Arab region during the last few years, many gaps and challenges still exist.

The response of Arab Governments to the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted these disparities, even if some measures were effective in the immediate term. The COVID-19 pandemic has opened up an opportunity to both assess previous social policy reforms, their effectiveness and impact, and to learn from global experiences not only in addressing repercussions of COVID-19 but also in the broader realm of social policy interventions.

Conceptual framework

Two main points are to be taken into account in terms of the conceptual framework used in this report.

The life-course approach adopted by the United Nations aims to ensure that all people have access to social protection when needed at all times throughout their lives, from birth to death. This also embodies the principle of leaving no one behind as stipulated in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development as it minimizes exclusion from benefits and social exclusion as a whole. A common categorization of life-course stages is the following:

- Pregnant women and infants (the first 1,000 days, from conception to 2 years of age);

- Children (from 2-18 years of age, sometimes separating those under 5 years);

- Youth (18-25, 18-30 or 18-35 years of age, depending on each country’s definition);

- Working age (18-60 or 25-65 years of age, again varying from country to country);

- Old age (60+ or 65+ years of age, rising in some countries according to changes in the retirement age).

The aim of this level of analysis in the report is to provide deeper insight into the key decision-making processes that are taking shape during the pandemic by Arab Governments and whether these are indicative of more fundamental restructuring of social policies. Given that most countries in the Arab region have a mix of social policy and protection actors comprising State, market, community, civil society, and family, the report highlights which actors are at the forefront of this provision, which is the basis of entitlements and whether the interventions are providing adequate benefits. This will help to analyse the likely consequences on income inequality and poverty in the longer term.

Social protection systems: in pursuit of an ideal

The two key concepts guiding this report are social policy and social protection. Social policy is concerned “with the ways societies across the world meet human needs for security, education, work, health, and well-being”. It addresses how “states and societies respond to national, regional and global challenges of social demographic and economic challenges and of poverty, migration and globalisation”.

Social protection can be broadly defined as “the set of programmes and interventions designed to preventing or alleviating poverty, vulnerability and social exclusion by supporting and protecting individuals and their families in the event of adverse income shocks, and by providing access to basic social services. Social protection instruments are a key element of social welfare policy.”

Social protection is also fundamental to achieving the 2030 Agenda. Through its contribution to the social and economic pillars of sustainable development, it is reflected directly or indirectly in at least five of the 17 SDGs (see box 1).

Target 1.3

Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable.

Target 3.8

Archieve universal heaith covarage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

Target 5.4

Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate.

Target 8.5

By 2030, acieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women ana men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value. [social protection is one of the four pillars of decent work]

Target 10.4

Adopt policies, especially fiscal,age and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality.

Pre-COVID social protection systems in the Arab region: gaps and challenges

Despite significant improvements in the extension of

social protection coverage in many parts of the world,

progress in building social protection systems pre-

COVID-19 was still lagging behind in other parts.

In the Arab States, the lack of data allows only a partial

assessment of effective social protection coverage. It is

estimated, however, that pre-COVID-19 only less than 30

per cent of people in the Arab region were covered by some

form of social protection. The social protection systems

in the Arab region were characterized by fragmentation

and lack of inclusiveness and transparency. The system

also suffered from underinvestment.

Figure 1 shows the share

of social spending as a percentage of the gross domestic

product (GDP). The graph shows that social protection

spending reached its highest values in Egypt (9.5

per cent), Jordan (9 per cent), Algeria (8.9 per cent) and

Tunisia (7.5 per cent), whereas levels of social spending

in Qatar, Yemen, the Sudan, and the Syrian Arab Republic

represent less than 2 per cent of GDP.

A more detailed view of social assistance spending by programme type is provided in figure 2, which shows heavy reliance on unconditional cash transfers across all countries and on food and in kind support in conflict-afflicted countries such as the State of Palestine and Yemen, but also in Egypt and Mauritania.

Figure 3 shows health expenditure as a percentage of GDP by country and in comparison to the subregional averages. For the latest available year (2018), spending ranges from a low of 1 per cent in the Sudan to a high of 4.4 per cent in Kuwait, with an average of 2.9 per cent.

2. Regional social protection responses to COVID-19

Key messages

-

-

In the Arab region, the response to the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of social protection measures demonstrated strong political will with the substantive disbursement of funds to alleviate the needs of vulnerable populations, and social solidarity through the innovative use and creation of solidarity funds, thereby drawing assistance from the private sector and other stakeholders to feed into these governmental social protection programmes.

-

-

-

Arab countries excelled in using innovative technologies for the delivery of social protection programmes, especially cash transfers that were delivered in few days to beneficiaries through newly created outlets, e-wallets and digital registration.

-

-

-

Despite all efforts exerted during the pandemic in the area of social protection programmes, overall coverage of these interventions in the region (except for Morocco) was low. Also, adequacy in terms of benefits in percentage of household expenditure and household income, namely, the adequacy of these interventions to meet households’ needs, was low in many countries such as Iraq, Jordan and Tunisia.

-

-

-

In-kind services and public procurement would be better suited to withstand the impact of fluctuating supply chains or prices that might make in-cash assistance less reliable (for example, in Lebanon).

-

-

-

The determination of targeting impacts the capacity of the COVID-19 response to incorporate a life-course approach (sociodemographic or economic indicators). The recalculation of cut-off points in the eligibility criteria in some countries in the Arab region yielded positive results, and needy people benefitted more from governmental social assistance programmes.

-

-

-

Governments may be able to leverage all programmes simultaneously to achieve a more effective COVID-19 response.

-

Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic, and the measures

introduced by Governments to contain the spread of

COVID-19, created a series of shocks that affected

hundreds of millions of people.

By 20 July 2021, there

were 190 million confirmed cases and 4.1 million deaths

from COVID-19 worldwide. Although the majority of cases

were in the Americas and Europe (123.3 million), no region

escaped, and 11.9 million cases were recorded in the

Eastern Mediterranean region by July 2021 (figure 4).

Global and regional social protection responses

Social protection contributed to the social policy

response to COVID-19 in a potentially positive way. On

the one hand, since increased hardship was triggered by

Government-imposed lockdowns that stifled economic

activity and created (temporary) mass unemployment,

these Governments felt obliged to provide income

support to compensate affected citizens for their lost

income. On the other hand, most countries already

had a set of instruments in place, in the form of social

protection instruments and delivery mechanisms, that

could be mobilized to deliver support.

Across Arab countries, social

assistance interventions were most prevalent in least

developed countries (LDCs) standing for 62.5 per cent of

the social protection-related support while GCC countries

constituted the highest share of active labour-market

programmes (figure 5).

Although most countries in the world implemented COVID-19 responses, the amount of protection relative to per capita income varied dramatically between countries and across regions, correlated mainly to national resource availability. The Arab region spent 0.5 per cent of per capita income, nearly similar to the spending of Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and the Pacific, and South Asia, compared to the global average of 1 per cent of per capita income. Latin and North America showed a higher share than the global average, at 1.4 and 2.5 per cent, respectively (figure 6).

Regional overview of responses to COVID-19

COVID-19 has created a global public health crisis, and responses to the pandemic have created economic and humanitarian crises at the national level.

1. Middle-income countries: Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, and Tunisia

Some middle-income countries used ‘shock-responsive’ mechanisms, temporarily increasing benefits paid to beneficiaries of existing cash transfer programmes and/ or registering new beneficiaries, at least for the duration of the COVID-19 crisis.

As per figure 7 and in terms of diversification of interventions, Egypt tops the list, followed by Jordan, Tunisia, and Morocco. Lebanon undertook the least diversified measures among middle-income countries, followed by Algeria.

-

Egypt

Egypt added 100,000-80,000 new beneficiaries [horizontal expansion] and large increased payments to existing beneficiaries [vertical expansion] of the conditional cash transfer programmes of the Ministry of Social Solidarity. Jordan

Jordan’s National Aid Fund (NAF) set up a sixmonth cash programme for poor and vulnerable households affected by COVID19- and paid topups to existing beneficiaries [vertical expansion]. The Zakat Fund also provided cash and in-kind assistance to old and new beneficiaries. The Hajati cash transfer programme was also expanded to include new beneficiaries [horizontal expansion].Morocco

Morocco paid 130-90$ per month for three months to 3 million informal-sector workers (half of the informal workforce) who were directly affected by the Government’s compulsory confinement policy [new programme].-

Tunisia

Tunisia paid two top-ups worth 17$ each to 260,000 beneficiaries of existing cash transfer programmes and two top-ups worth 68$ each to 623,000 vulnerable existing beneficiaries of lowcost health-care cards [vertical expansion]. Oneoff cash transfers worth 68$ were paid to 300,000 vulnerable informal-sector workers and to 70,000 self-employed workers [new programme]. Algeria

Algeria introduced a once-off top-up solidarity allowance worth 80$ for families in need who were impacted by COVID-19 measures.Lebanon

In Lebanon, the High Relief Authority delivered social assistance to people adversely affected by COVID-19 lockdown measures.

2. Conflict-affected countries: Iraq, Libya, State of Palestine, Syrian Arab Republic, and Yemen

Existing humanitarian relief programmes were used where available as was the case in Yemen. In Palestine and the Syrian Arab Republic, responses to COVID-19 included expanding support to existing platforms such as e-payments and sharing databases across ministries to identify eligible beneficiaries. In terms of diversification of measures in conflict-affected countries, Iraq tops the list followed by Yemen and Palestine (figure 8).

3. Least developed countries: Mauritania, Somalia and the Sudan

The three LDCs in the region have a limited set of social protection programmes in place, the majority of which is donor-financed. Mauritania, Somalia and the Sudan set up special programmes to deliver financial assistance to COVID-19-affected groups, using, at times, innovative platforms. As per figure 9 and in terms of diversification of measures, Mauritania tops the list, followed by the Sudan, with Somalia having undertaken the least diversified measures.

4. Gulf Cooperation Council countries: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates

Social protection in the six GCC States is dominated

by religious charity such as zakat and Ramadan

payments. In Kuwait, for instance, Zakat House

beneficiaries received additional payments, and a

new cash transfer programme was set up; and in

Bahrain, social assistance beneficiaries received

double payments.

As per figure 10 and in

terms of diversification of measures, Kuwait tops the

list, followed by Oman and Bahrain.

3. Financial sustainability

Key messages

-

-

Arab countries have responded rapidly to the economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis on firms and households and to keep their financial markets in operation. By May 2021, most Arab countries committed to fiscal stimulus packages. The GCC showed the highest spending, at $69.9 billion, compared to $24.78 billion spent by the other subregions. These stimulus packages are mainly based on foregone or re-allocated funding and do not involve major reforms in the tax base.

-

-

-

Among Arab countries for which data as at June 2021 is available, the private sector in Tunisia contributed $410 million as a response to the pandemic and, in Morocco, attracted $104.5 million. Philanthropies have played a major role in raising some $2.2 million in Morocco and the United Arab Emirates.

-

-

-

By making clean energy transitions central to their recovery plans, Arab oil-producing countries can pave the way for more robust structural changes to support economic recovery that is environmentally sustainable as much as it is financially sustainable.

-

-

-

A major lesson learned from the COVID-19 pandemic is the importance of further investment in the emergency preparedness of the social protection system. Jordan is a noteworthy example showing crisispreparedness despite regional volatility, fiscal constraints and economic shocks.

-

-

-

Investing further in social protection and diversifying the range of financial resources, in particular, through equitable tax collection (for instance, progressive and corporate taxation) are all important lessons for Arab countries who are struggling with fiscal deficits and conflict.

-

-

-

Investing further in social protection and diversifying the range of financial resources, in particular, through equitable tax collection (for instance, progressive and corporate taxation) are all important lessons for Arab countries who are struggling with fiscal deficits and conflict.

-

Resource allocations and expenditures, ensuring access for all

This section outlines the sources and types of financial

measures undertaken by the Arab countries and provides

an overview, by subregion, of key sources of finance.

Arab countries have responded rapidly to the economic

effects of the crisis on the private sector and households

and to keep their financial markets in operation. The target

beneficiaries of the COVID-19 interventions have been

vulnerable groups such as women, the elderly, children,

and informal workers using a mix of social assistance

and tax-relief measures.

The pandemic measures thus present risks for

macroeconomic stability, with the increases in fiscal

deficits and governmental debts in all Arab countries in

2020 posing an important challenge for the introduction

of a sustainable life-course approach to social policy.

Fiscal deficits of Arab countries have increased in 2020

as a result of a decline in oil prices amidst the COVID-19

pandemic (figure 13).

Out of the total fiscal support in the Arab region of $94.8 billion, $70 billion were provided by GCCs whereas middle-income countries, LDCs and countries affected by conflict spent only $19.4 billion, $4.1 billion and $1.3 billion, respectively (figure 14). The total global fiscal support was $18.7 trillion, most of which came from high-income countries.

Spending on social protection: global and regional success stories

This section highlights successful regional and global experiences to learn from or to further develop. Success is measured in terms of governmental capacity to reallocate spending for more effective social protection during the pandemic rather than the introduction of a life-coursebased approach to overall social protection.

Jordan

The Central Bank of Jordan made available $705 million by reducing compulsory reserves of commercial banks, allowing banks to postpone loan repayments in impacted sectors and extending guarantees on loans for small and medium-sized enterprises.United Arab Emirates

The Government of the United Arab Emirates allocated a flexible stimulus budget amounting to nearly 256 billion Emirati dirhams, or $70 billion. All banks operating in the United Arab Emirates were granted access to loans and advances at zero cost against collateral provided by the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates.Mauritania

Mauritania is an example of a lower-income country that has taken innovative financial measures. A special fund for social solidarity was created through governmental contribution of $170 million. This helped supports 206,000 households with a cash transfer of $60 per person. The extension of the fund by an additional $13.5 million is possible.-

Pakistan

The main response strategy of the Government of Pakistan was the launch of the Ehsaas Emergency Cash (EEC) programme, allocating 203 billion Pakistani rupees (approximately $1.2 billion) to deliver one-time emergency cash assistance to 16.9 million families at risk of extreme poverty. Indonesia, the Philippines, South Africa, and Uzbekistan

These countries deployed their financial reserves and reprioritized spending – the most common approach used by many countries.Hong Kong, Serbia and Singapore

These are good examples of how high-income countries can provide universal cash transfers. Hong Kong spent $9.16 billion for cash payouts through deficit spending. In Serbia, the universal cash benefit cost $712 million, which was part of the 3.9 billion stimulus package.

Implications for the sustainability of resource allocations in social policy: structural changes for the post- COVID-19 recovery period

In line with the current thinking, this chapter has

highlighted the immense fiscal efforts of Arab countries

in combatting the economic impact of COVID-19. This

statement applies for high-, middle- and low- income

countries in the Arab region. Most countries

in the region will likely recover their GDP during the postrecovery

period.

In terms of the main implications for the future

sustainability of resource allocation and financing of

social protection, most Arab countries have deployed

short-term measures to smoothen consumption

such as tax relief and cash transfers. This means that

such measures are not permanent especially given

fiscal deficits.

Key recommendations for sustainability thus include the following:

- Improved macrofinancial planning for the social protection sector.

- Institutional capacity for sustainable fiscal policies based on taxation including progressive taxation and corporate taxes that can redistribute income and provide essential public services for all in an improved manner.

- Putting in place the technical and administrative infrastructure for new schemes after the pandemic. This can be the foundation for social protection systems to build capacity and preparedness.

- Monetary policy to influence inflation and unemployment levels through the availability and cost of credit to firms and households. For example, the control of interest rates influences levels of confidence and, therefore, spending in the economy which, in turn, has an impact on the demand for goods and services, and, consequently, jobs.

- Exploring the possibility of minimum wage or basic income guarantees and technological innovations.

4. Global and regional innovations in social policy

Key messages

-

-

Although COVID-19 has created immense hardship for millions of people in the Arab region and across the world, it has also generated innovative responses and important lessons for Governments that should not be forgotten once the current crisis is over.

-

-

-

All the innovative efforts by Governments to ensure citizens’ uninterrupted access to basic social services in health care, education and social protection that were introduced during 2020 should be sustained and built on post- COVID-19 because they represent a minimum provision of essential services in line with the international human rights law.

-

-

-

Investments that were made in innovative solutions (such as online learning and telehealth applications) must be supported through investments in digital infrastructure and reduced costs of access to mobile and online technologies. Regional Innovations in Social Policy.

-

-

-

Innovative strategies must be developed and underpinned by legislation, either to incorporate migrant workers, foreign residents and refugees into domestic social protection systems or to ensure the portability of benefits across national borders.

-

-

-

Health insurance, or free and equitable access to health care, needs to be provided to all citizens and residents as a fundamental human right. The case of Morocco provides an instructive example of how this might be achieved.

-

-

-

Many Arab countries established partnerships with ministries of communication to facilitate access to services and increase the speed of the Internet.

-

Innovations in access to education

The COVID-19 pandemic has created the largest disruption of education systems in history. UNESCO estimated that, by end-March 2020, 165 countries had closed schools, universities and other learning spaces nationwide, affecting 1.5 billion children and youth or 94 per cent of the world’s student population, and 99 per cent in low- and lower-middle income countries. With a view to supporting the development of teaching and learning materials to enhance the capacity of instructors delivering online, UNESCO has made available openly licensed tools that can be used by Governments and institutions.

In the Arab region, 13 million children and youth were out of school due to conflict pre-COVID-19. Due to the pandemic, more than 100 million learners across the region have been affected by school closures. Since the outbreak of the pandemic and the national lockdown measures, countries in the Arab region implemented a variety of solutions. Online learning gained ground as most countries introduced online platforms for continued learning.

Preventing the learning crisis from becoming a generational catastrophe needs to be a top priority for world leaders and the entire education community.

In this regard, decision makers are encouraged to pursue the following recommendations and actions:

Ensure safety for all

The United Nations and the global education community have developed guidance to help countries through the timing, conditions and processes for reopening education institutions. A key precondition is being able to ensure a safe return to physical premises while maintaining physical distancing and implementing public health measures, such as the use of masks and frequent handwashing.Plan for inclusive reopening

The needs of the most marginalized children should be included in school reopening strategies. Adequate health measures need to be provided for students with special needs. Conducting assessments to estimate learning gaps and prepare remedial or accelerated learning programmes is essential at the time of reopening.-

Focus on equity and inclusion

Measures to build back resiliently and reach all learners need to understand and address the needs of marginalized groups and ensure that they receive quality and full-term education. Strengthen financial resources mobilization and preserve the share of education as a top priority

Education ministries should strengthen dialogue with ministries of finance in a systematic and sustained way to maintain and, where possible, increase the share of the national budget for education, particularly in contexts when internal reallocation is feasible.Towards the recognition of online qualifications

In many countries, and the Arab region is no exception, many higher-education systems do not accept online qualifications. Authorities and universities are concerned about the quality of qualifications obtained exclusively through online provision.

Innovations in access to health care

Limited access to health care is a major contributing cause of poverty. Every year, an estimated 100 million people fall into poverty because of unaffordable healthcare expenses.

Almost all countries allocated additional fiscal resources to their national health services in 2020, under COVID-19 stimulus packages that aimed to ensure accessible, quality health services for COVID-19 patients while protecting frontline health workers. Countries with well-functioning health systems and health insurance schemes in place that already covered all or most of the population were better able to respond to COVID-19 in a quick and inclusive manner. Examples of innovative responses include the following:

Qatar and Saudi Arabia

Provided free screening and testing for migrant workers.Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates

Supported COVID-19 vaccine research and trials, in partnerships with China and other countries.-China, the Philippines and Vietnam added COVID-19 testing and treatment to their health-care benefits and extended access to these benefits to informal workers.-

Thailand

Gave all COVID-19 patients, both citizens and foreign residents or visitors, free access to health care under its Universal Coverage Scheme for Emergency Patients.

Innovations in social protection

Four main areas of innovation in social protection have been observed in recent years. All of these were highlighted by COVID-19 in 2020, which provided an impetus to accelerate ongoing trends.

1. Towards universal social protection

By exposing the glaring gaps in social protection

provisioning across the world, especially in low- and middleincome

but even in high-income countries, COVID-19 has

given fresh impetus to advocates for universal – or at least

more inclusive – social protection systems.

The world’s first basic income grant was piloted in a

rural town in Namibia for 24 months in 2008-2009.

Food poverty decreased dramatically, economic activity

and earnings increased due to local income multipliers,

access to education and health services improved,

levels of indebtedness fell, crime rates also fell, and child

nutrition indicators improved.

“At the level of

the Arab region, there has been ‘accommodation’ of

social protection into existing political and institutional

frameworks which fall short of the more transformative

potential hailed in the literature.” Social protection efforts

in this region have instead been dominated by a reverse

trend, namely, pressure from international agencies such

as the World Bank to dismantle universal food and fuel

subsidies and replace these with targeted cash transfers.

A notable exception is Morocco, which committed to

implement a progressive expansion of coverage of family

allowances and health insurance, to achieve universal

coverage by 2024.

2. Social protection for informal workers

There is a growing consensus on the need to extend social

protection coverage to informal workers who are eligible

for neither social assistance (which mostly targets nonworking

vulnerable groups) nor social insurance (which

targets formally employed workers who pay contributions

into social security funds). COVID-19, which has affected

more than 1.5 billion informal workers, highlighted this

gap and gave renewed impetus to this issue.

Apart from informal workers, other vulnerable categories

that are often excluded from social protection include

migrants, refugees and IDPs. The Arab region currently

hosts the highest numbers of refugees and forcibly

displaced people in the world.

Migrants

Migrants comprise a significant share of the workforce, especially informal workers, in several countries in the Arab region, especially in the GCC where they have supported the functioning of health care, nursing, transport, agriculture, and the industrial sector, in particular the oil industry, throughout the crisis. However, migrants who were forced to stop working have been extremely vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many were stranded in foreign countries due to travel bans, with no entitlement to local social assistance or social insurance schemes.Remittances

Remittances from citizens working abroad, especially in Europe and the Gulf countries, make a major contribution to the economies of several countries in the MENA region. In Egypt and Lebanon, for instance, remittances accounted for 10 per cent and 12.5 per cent of GDP, respectively, in 2019. Due to the economic shock caused by COVID-19, which reduced the incomes of remitters, remittances were projected to decline by 20 per cent in 2020.-

Refugees and IDPs

The number of refugees and IDPs in the MENA region has increased sharply during the last decade, largely due to the protracted civil war in the Syrian Arab Republic. Refugees living in camps and high-density housing areas were at heightened risk of contracting and spreading COVID-19.

3. School feeding adaptations

An estimated 1.6 billion children in 197 countries faced

disrupted education during 2020 due to school closures,

and 370 million of these children lost access to their daily

meals at school. Many countries with school feeding

programmes adopted a variant of WFP’s ‘school feeding

at home’.

School feeding at home takes several forms (see box

2).

Libya: While schools were closed due to COVID-19, the Ministry of Education continued its teaching programme through distance learning. The World Food Programme (WFP) supported the Ministry by providing 2 kg boxes of mineral-and vitamin-fortified date bars as take-home ration to 18,000 learners in southern Libya, enough to cover 30 per cent of the family’s daily nutrition needs for five days.

Colombia: After schools were closed in April 2020 because of COVID-19, 112,000 learners lost their access to school meals. For 86,000 of these children, meals at school were replaced with take-home rations. One family member collected the food rations – a nutritious package that included cereals, dairy products, cooking oil, and fruits.

Congo: When schools were closed due to COVID-19, the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education delivered an ‘education at home’ programme on the radio and television. At the same time, WFP launched ‘school feeding at home’, providing rice, peas, vegetable oil, salt, and sardines as take-home rations.

Cambodia: With support from WFP, the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport gave 10 kg of donated rice to more than 100,000 learners at over 900 primary schools, to protect their families against the livelihood shocks associated with COVID-19 restrictions. As a one-off transfer that would be consumed by the entire family, this intervention probably had only limited impact on child nutrition outcomes.

Honduras: The National School Feeding Programme, which delivers hot meals to 1.2 million children, was suspended when schools were closed. School feeding committees prepared food parcels (including rice, beans, cornmeal, and oil), following COVID-19 safety protocols developed by WFP and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The parcels were collected from schools by adult relatives of each learner. In some areas, to avoid crowding at schools, teachers delivered the parcels door-to-door as take-home rations, using bicycles and motorbikes.

4. Innovations in the digital delivery of social protection

COVID-19 accelerated an ongoing process worldwide,

namely that of transitioning from manual delivery

of social services to delivering certain components

of these services via digital platforms, such as the

Internet, television, mobile phone, and social media

applications.

As seen in the cases of Colombia and Pakistan, financial

inclusion is a secondary benefit of several programmes

that deliver income support through digital platforms.

Another example is the case of Brazil, which created bank

accounts for millions of new beneficiaries in 2020 (box 4).

Brazil’s Single Registry was used to deliver income support to three categories of beneficiaries in 2020, under the Emergency Aid (EA) and Extension of Emergency Aid (EEA) provisions of the Government. These categories are as follows: (a) households already receiving cash transfers from the Bolsa Familia programme received additional support; (b) households already registered in the Single Registry but not benefiting from existing programmes were added to beneficiary lists; and (c) informal workers, self-employed and unemployed people applied through a digital registration platform and were processed on the Extra Single Registry. The new digital platform (application plus website) was created by a State-owned bank. Successful applicants received payments into a digital savings account, which was also the modality used to pay other social protection beneficiaries during the lockdown. The Extra Single Registry prompted large-scale financial inclusion, as 48.6 million new savings accounts were set up for EA and EEA cash transfer recipients.

5.Conclusion

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, social protection systems in the Arab region were weak, fragmented, costly, unsustainable, and not inclusive. They were marked by underinvestment and exclusion of vulnerable populations. The COVID-19 crisis highlighted the problems and presented a historic opportunity to address some of the challenges in social protection systems. It also provided many lessons learned in various countries worldwide and instigated some useful innovations.

In the Arab region, the response to the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of social protection measures demonstrated strong political will through the substantive disbursement of funds to alleviate the needs of vulnerable populations, and social solidarity through the innovative use and creation of solidarity funds. This effort drew assistance from the private sector and other stakeholders to feed into these governmental social protection programmes.

In addition, COVID-19 spending varied according to different areas, including social assistance (cash transfer, school feeding and others), loan and tax benefit (tax exemption, interest rate waivers and others), social insurance (unemployment waiver, sick leave pensions and others), labour markets (wage subsidies, paid leave and work from home), health-related support (free vaccines, testing, health-care systems, and others), financial policy support (soft loans and credit support, tax exemption and others) and general policy support (creation of funds, digital solutions and others).

Most Arab countries have provided temporary consumption smoothing programmes such as cash assistance or tax relief to vulnerable groups, including the unemployed, women and children, rather than extending social insurance and life-course programmes. The reason for this is the absence of an adequate tax base and reduced fiscal space resulting from high levels of debt, poor economic performance and reduced oil revenues. These factors account for the gap in social protection coverage during the pandemic and recovery period.

During the pandemic, instead of putting in place new legislation, most countries relied on extrabudgetary funds or executive decrees to deliver the spending packages. While these measures promptly facilitated spending on social protection programmes, they undermined accountability mechanisms of fiscal policy decisions in Arab countries.

Overall, the initiatives analysed in this report show that, whilst examples of small-scale measures exist that may lay good foundations for a life-course approach in Arab countries, challenges still remain in terms of the longterm financing and reformulation of social protection beyond targeting low-income groups. Therefore, a transition period will be needed between current and reformed systems that may require solidarity funding to bridge the gap. Meanwhile, contingency planning can help in addressing potential future crises.