Inequality in the Arab region:

Food insecurity fuels inequality

Foreword

Food insecurity is a brutal face of inequality. It divides nations and breaks societies.

Stories of hunger are millennia old, yet the narrative is growing increasingly complex under

globalization, climate change, population growth and geopolitics.

In the Arab region, food insecurity is currently being aggravated by the impacts of the war

in Ukraine and the global cost-of-living crisis, which is heavily affecting food prices. In

some countries, conflict has destroyed the ability of farmers to produce food and has

devastated the livelihoods of people so that they can no longer afford nutritious food. In

other countries, economic crises have decimated livelihoods and the ability of national

Governments to provide for their populations.

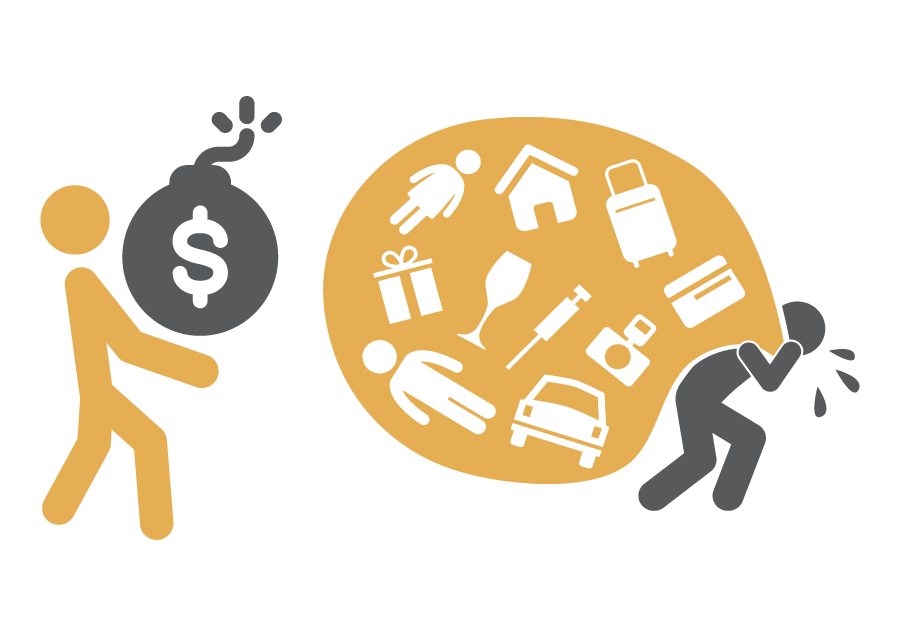

Hundreds of millions of families across the Arab region live in a vicious cycle of poverty

and hunger. Families are making difficult decisions as to how to portion their food and what

they can cut from their daily diet. Those facing overlapping inequalities are the most

vulnerable to hunger. The threat of hunger increases the desperation of the already

desperate, forcing them to take unprecedented risks. They may take dangerous jobs or sell

their only assets just to feed their families, exacerbating the vicious cycle of poverty and

hunger.

Children living in poverty in the Arab region are at risk of being left behind. Without

access to sufficient nutritious food, they are unlikely to develop on par with more

fortunate, well-nourished children. They are more likely to experience poor health and are

less able to afford decent medical care. Their education and psychosocial development will

never catch up with that of their peers. They will have fewer opportunities available to

them as they grow up and will face life-long exclusion and compound inequalities.

Food insecurity transcends hunger. It affects sovereignty and stability. Globally and

throughout history, well-fed populations have been those to flourish; however, when

populations are kept in poverty and denied access to food, social unrest, instability and

violence follow.

The Arab region holds enormous wealth. We have enough food in the region to feed our

populations. So why do we still face food insecurity?

The answer lies in inequality. The Arab region has the greatest income inequality in the

world. It is also characterized by massively unequal access to nutritious, healthy food and

the ability to afford it. One third of the region’s population are hungry and another third

of the population are obese.

The solution requires solidarity and redistribution. One nation alone cannot solve the

problem. Arab leaders need to come together to increase food availability, access,

utilization and stability. We must support our agricultural sector and workers, adopt

innovative digital technologies and promote regional trade. We must focus on redistribution

through progressive policies and comprehensive social protection systems. We must also

respond to the dangers of climate change by reducing our emissions, adapting to new

practices and enhancing disaster risk management.

We must act now to deliver practical policy solutions to feed our communities. It is

unacceptable that anybody should face hunger, let alone starvation, when there are enough

resources for all. Food security is a necessity, not an option. We must leave no one behind

in our quest to feed the region.

Rola Dashti, Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations and Executive Secretsry of the Economic ans Social Comission for Western Asia (ESCWA)

Executive Summary

The Arab region is the most unequal in the world, and inequality is increasing in various aspects. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, high interest rates and growing debt burdens in some countries, the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, and the impact of the war in Ukraine – which has disproportionately affected food and energy prices – are all contributing to widening inequality, both between and within countries.

Considering disparities between countries in the Arab region, oil producers are set to benefit from the current environment as Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries gained as much as $5.8 billion in 2022 as a direct result of the war in Ukraine. By contrast, middle-income Arab countries lost about $6.7 billion due to higher food and energy prices, which would elevate their high public debt burdens and limit the financing available for basic public services. Already, regional public spending on health, education and social protection is below international benchmarks. Further strain on public service provision will accentuate inequality by limiting the possibility of access to basic public goods, which are much needed to provide opportunities and sustain a minimum standard of living for the most vulnerable and those living in poverty.

Concerning disparities within countries, wealthy Arab citizens are getting richer and more people in the region are becoming millionaires than ever before. In 2021,

20,000 individuals in the region newly became millionaires. At the same time, low-income Arab citizens lost one third of their wealth in 2021 and 120 million people across the region live in poverty. Gender inequality is also rife. Women in the Arab region earn on average less than a quarter of what men earn, due to societal norms and unequal legislation that limits their labour force participation and career growth. The most gender-equal country in the region only ranks 68th in the global gender gap index, whilst three countries in the region sit in the bottom 10 of the index.

People across the region recognize that they live in a polarized society. A poll by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) revealed that almost four-fifths of respondents believed that they lived in an unequal society, and more respondents considered that inequality would grow over the coming five years compared to those that believed it would decrease.

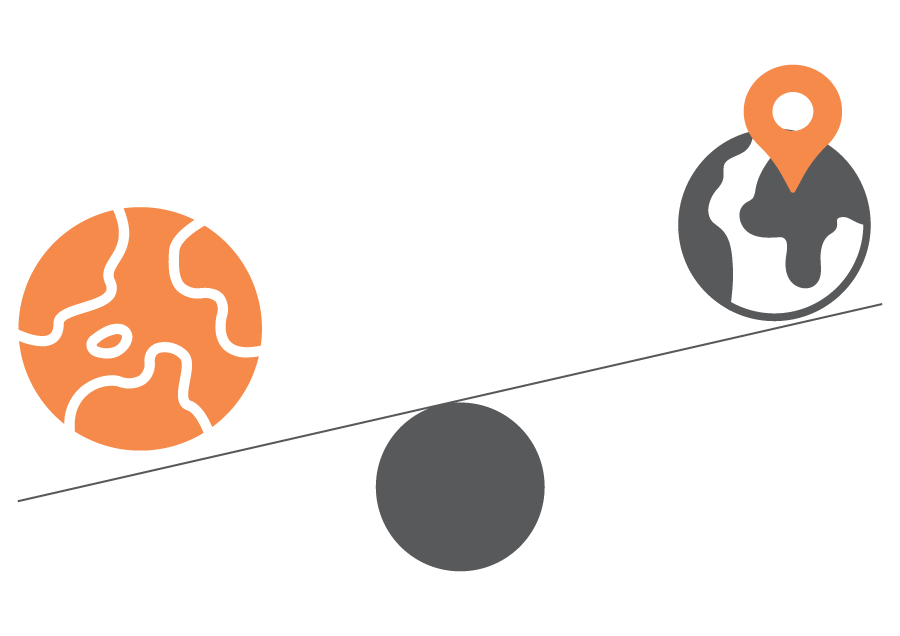

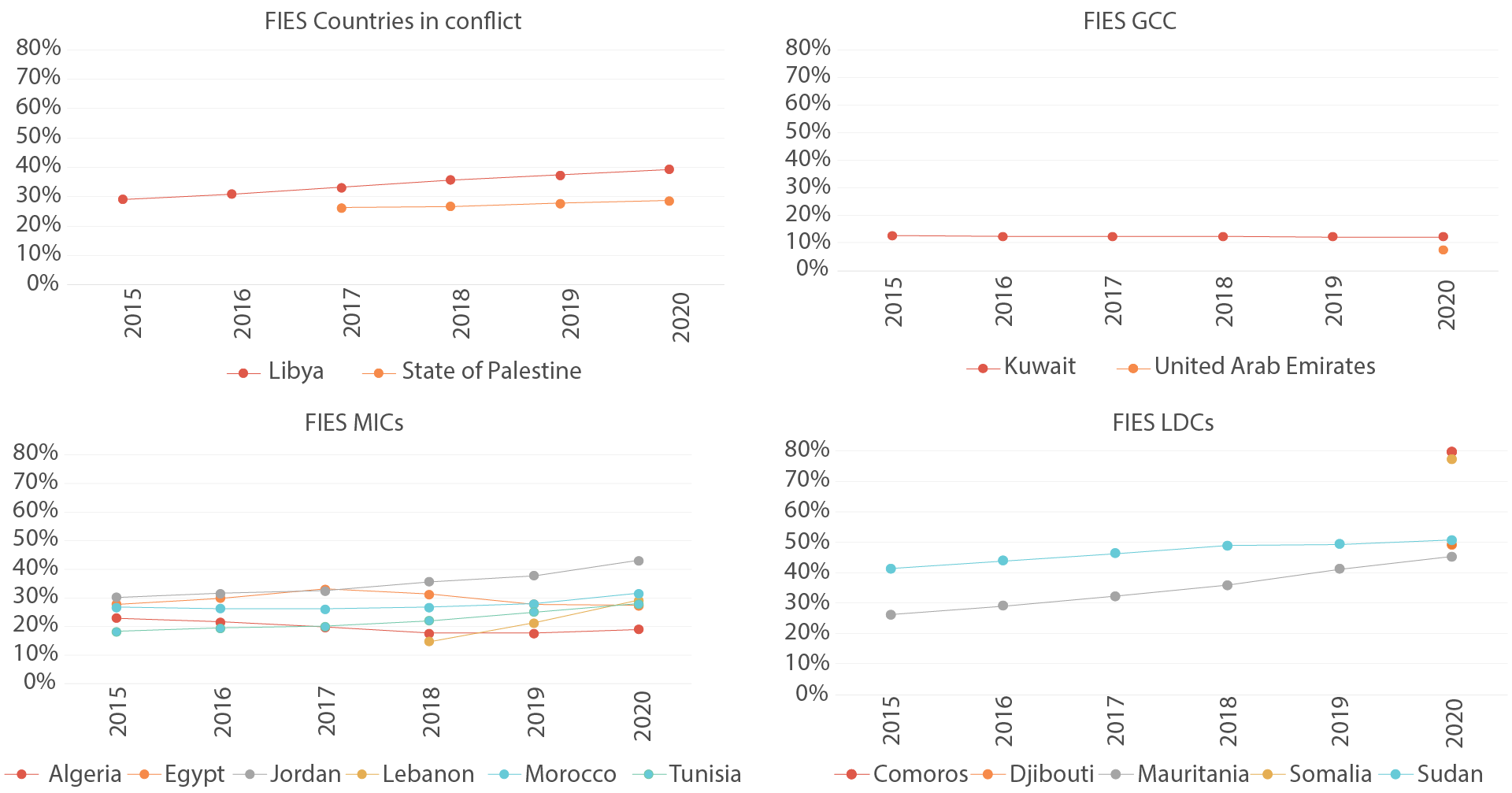

Inequalities in income and wealth are mirrored by inequalities in access to food.

Between countries, Arab least developed countries (LDCs) have five times higher food insecurity than those in the GCC, and much less access to clean water and sanitation, essentials for safe food consumption.

Within the countries of the region, 181 million people, close to 35 per cent of the Arab population, are food insecure;

12 million more than they were just one year ago. The majority of food insecure people also live in poverty. Not only are more people in the region hungry, the extent of their hunger is also more severe. There are 54 million people across the region facing severe food insecurity; an increase of 5 million over the last year. There is a real risk that famine will affect at least 460,000 people in Somalia and Yemen. Obesity rates across the region are also soaring: 29 per cent of the Arab population are obese, twice the global average.

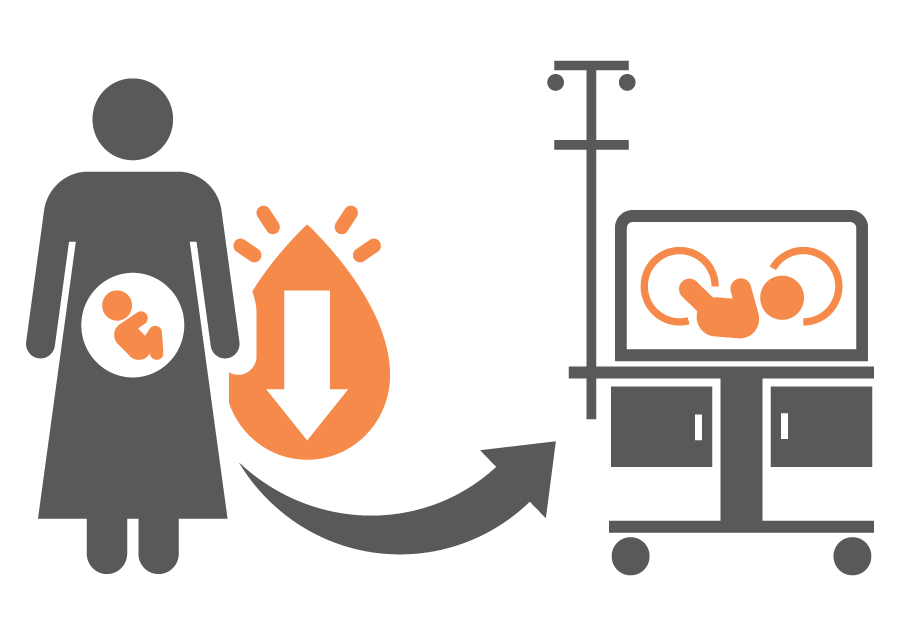

Women are more likely to experience both undernutrition and obesity, both of which threaten the health and well-being of the population. Women of reproductive age are also more likely to face anaemia (estimated to affect one third of women of reproductive age), which increases the likelihood of babies being born prematurely and of low birth weight, and reinforces the intergenerational pass-down of inequality.

Food insecurity is multifaceted. Climate change-induced floods and drought, economic crises and conflict and occupation all contribute to food insecurity in the Arab region and affect those living in poverty much more than the wealthy. The compound effect of these crises creates a more extreme impact than the individual sum of each crisis.

Limited food production in the region and massive food waste also contribute towards food insecurity. The Arab region produces less than half of the food it consumes, importing the remainder of its needs. There is enough food to feed everyone in the region, but food waste, combined with high import prices, causes millions to go without.

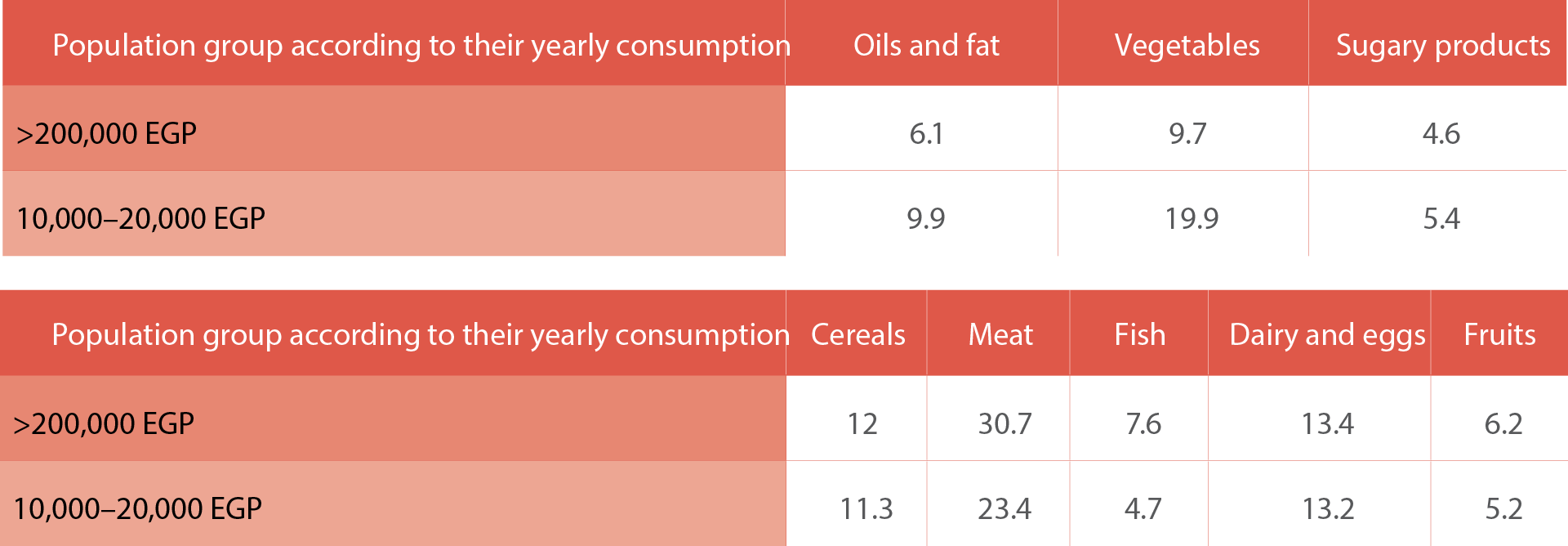

Still, poverty is the greatest determinant of food insecurity and whether a household can afford a safe and nutritious diet. The average Arab household spends one third of its income on food; poor households spend a much higher proportion, with their food choices being impacted by their monthly earnings.

This report analyses the four pillars of food security: access, availability, utilization and stability, from an inequality lens. It provides policy recommendations to address food security from the perspective of inequality.

It also calls for regional solidarity to redistribute resources from those that have plenty (Governments, corporations and individuals) to those that do not. A wealth solidarity fund can support regional redistribution, as can greater use of progressive fiscal policy to build comprehensive social protection systems. Social protection should not only protect against the immediate deprivations of poverty, but also provide assets, opportunities and skills so that beneficiaries can be permanently lifted out of poverty. Increased investments in health, education and social protection would support the impact of social protection systems. National nutrition strategies can reduce both undernutrition and obesity, and increase the public’s awareness of healthy eating and exercise practices.

Finally, this report provides recommendations to make agricultural systems, and to some degree social protection systems, more shock resistant, in order to reduce the impacts of shocks on the most vulnerable. Early warning systems, disaster management units, and climate change mitigation and adaptation can also protect against the growing impacts of climate change. When shocks do occur, immediate humanitarian assistance, without political implications, is key to protecting the Arab population.

Introduction

We are facing hunger on an unprecedented scale, food prices have never been higher, and millions of lives and livelihoods are hanging in the balance. The war in Ukraine is supercharging a three-dimensional crisis – food, energy and finance – with devastating impacts on the world’s most vulnerable people, countries and economies. All this comes at a time when developing countries are already struggling with cascading challenges not of their making – the COVID-19 pandemic, the climate crisis, and inadequate resources amidst persistent and growing inequalities.

Source: United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres, Global Report on Food Crises, 2022

Uncertainty once again dominates multiple economic and social realities globally, and the Arab region is no exception. The world is facing several compounded crises which are contributing to food insecurity: increasing inequalities in access to resources and opportunities; rising inflation; increasing food and fuel prices; global supply chain challenges; the impact of climate change; and the lack of strong, resilient local and regional supply networks. The combination of these factors has led to the worst conditions witnessed in recent times and could threaten the stability and prosperity of nations around the world.

The record levels of high food and fuel prices have triggered a global crisis that is driving millions more into extreme poverty, magnifying hunger and malnutrition while threatening to erase hard-won gains in development. The war in Ukraine, supply chain disruptions and the continued economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, along with increased debt and high interest rates are reversing years of development gains and pushing inflation and notably food prices to all-time highs.

The complexity and force of these crises are evident in the Arab region and are shaping and driving inequalities given the already weak regional resilience regarding capacity to absorb shocks and the historically rooted inequalities.

This second edition of the Arab inequality report follows the same approach as the first edition, “Inequality in the Arab region – A ticking time bomb” (2022), which examined the challenge of youth unemployment in the region. The present report is also inspired by the Pathfinders Alliance for Action on Inequality and Division that seeks to identify practical and politically viable solutions to meet Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10 on reduced inequality. This report presents the latest findings on inequality in the Arab region so as to inform public policy design. It focuses on the combination of the perfect storm of the cost-of-living crisis, food insecurity and energy poverty as factors of inequality hitting the Arab region. It also examines the challenges facing food security in the region, taking into consideration the latest global and regional developments. It provides a practical set of actions that identify how opportunities can be shared more equally to reach the most vulnerable populations and reduce inequalities in food security.

The report has three main purposes. First, to provide an update on the multidimensional forms of inequality that were identified in the first edition of the inequality report, which are: wealth concentration and inequality; income poverty; income inequality; and gender inequality. Second, the report flags the issue of food security as a significant form of inequality that can threaten the region’s security. Third, the report discusses alternative policy solutions that could tangibly reduce inequality, particularly the pertinent challenge of food security in the region.

The report is based on a desktop review, in addition to a public online survey on food security in the Arab region. The survey was disseminated on social media platforms to solicit people’s perceptions on food security in 2022. The purpose of the survey was to understand the perceptions and concerns of people in the Arab region in general and on food security in particular. The survey was not based on representative samples but on random responses from social media users, and as such results are indicative and cannot be generalized. Informative interviews were conducted with policymakers from the Arab region to complement the findings of the online survey. Case studies in four countries (Egypt, Iraq, Mauritania and the State of Palestine) were conducted using health and demographic surveys, as well as household expenditure and consumption surveys to analyse inequalities in food consumption patterns.