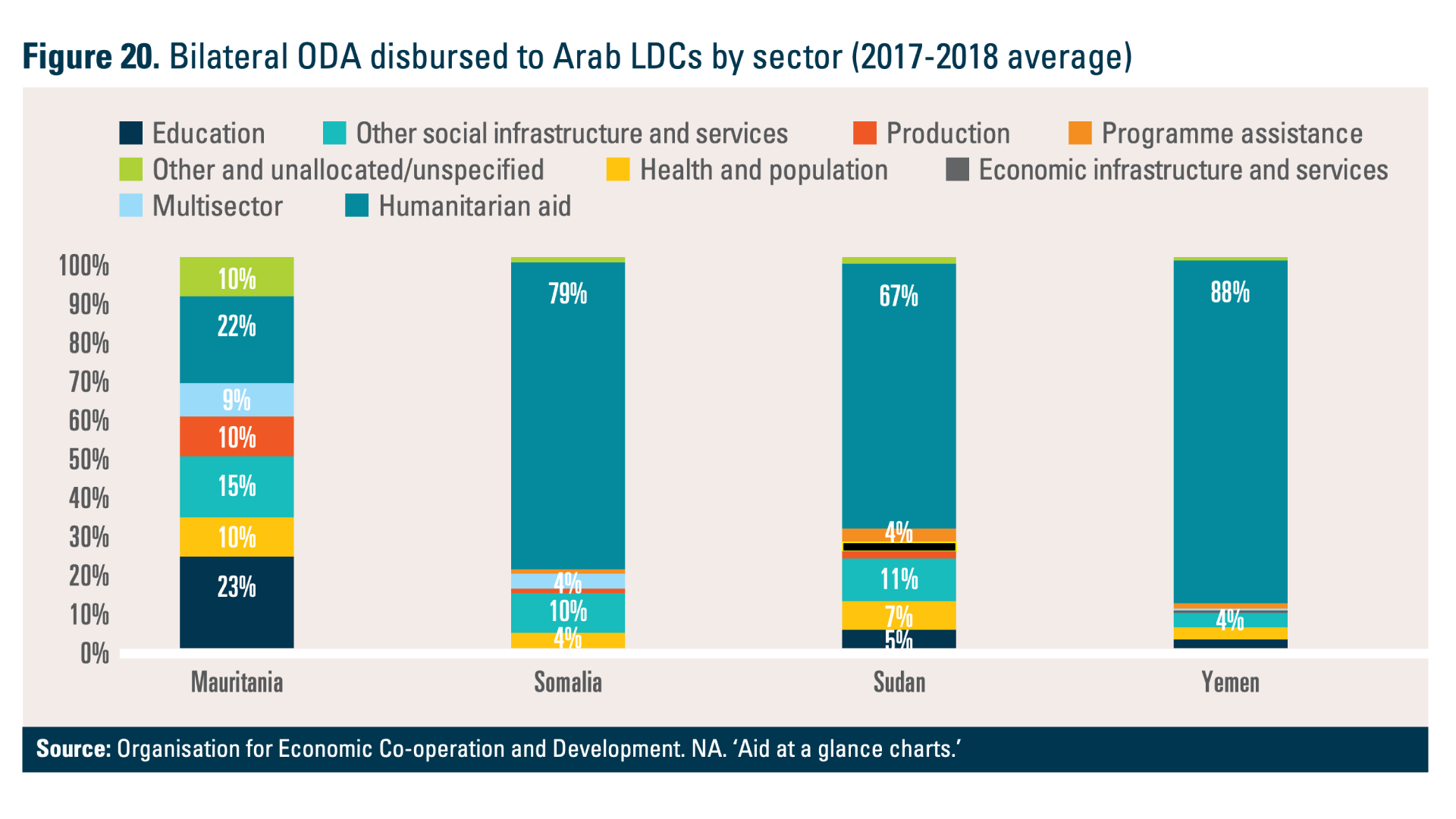

● Deliver on aid commitments promptly;

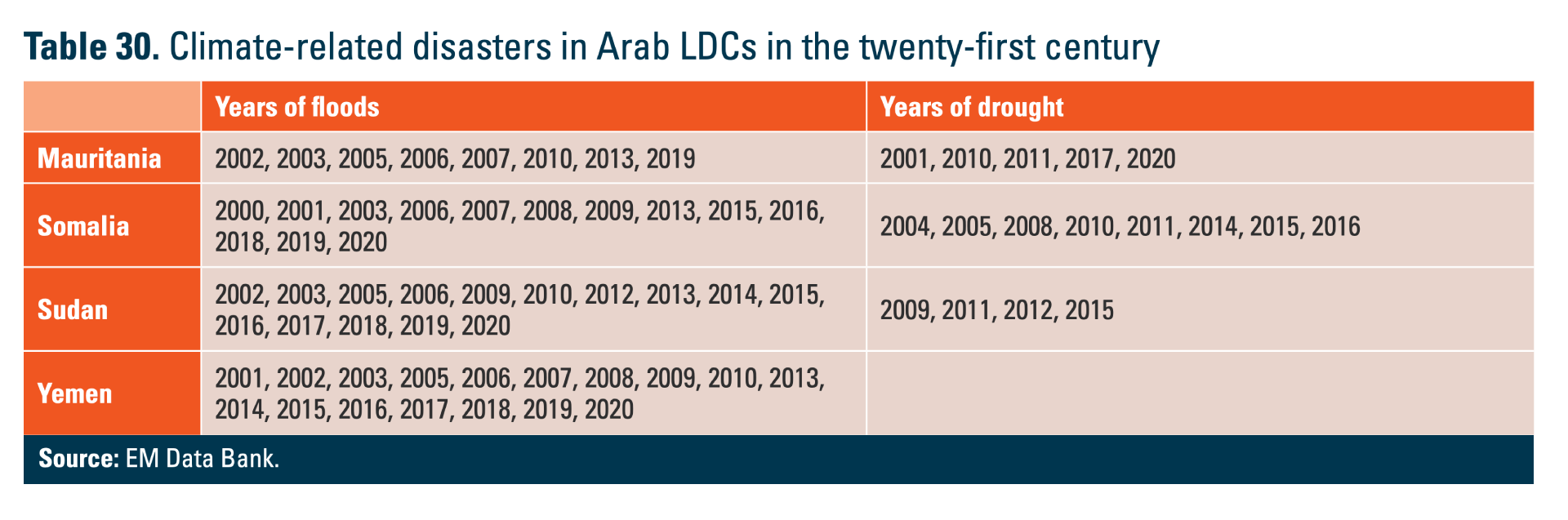

● No investments worsening climate change should be made;

● Release hard currency capital in overseas capital as needed by each State;

● Cancel LDC debts. As the challenge of indebtedness in the Arab LDCs has deepened,

urgent measures need to be taken to reach sustainable debt levels. If cancellation is unfeasible,

the debts need to be restructured adding flexibility to address external shocks and natural hazards;

● Ensure access to other sources of finance, including blended finance and investment promotion:

- Additional resources need to be allocated to the rehabilitation and expansion of infrastructure to

facilitate supply chains, support trade and economic activity, attract investment and facilitate private

sector development;

- Funders should focus on productive investments, supporting national entities and investments improving

social resilience and creating employment of nationals.

●Private sector FDI should prioritize investments which create ‘decent work’ jobs. In the case of

extractive industries, nationals of the LDCs should be trained and employed to fill positions at all levels.

Investment in productive industrial enterprises adding value to local raw materials should be prioritised;

● Facilitate the transfer of remittances to LDCs and the employment of LDC nationals in their states;

● Improve terms of trade for LDC exports, thus eliminating some of the imbalances in their balance of payments;

● Resource mobilization will be among the greatest of challenges. Therefore, development partners and the

United Nations and Bretton Woods institutions must link their aid to development programmes with economic

and social returns;

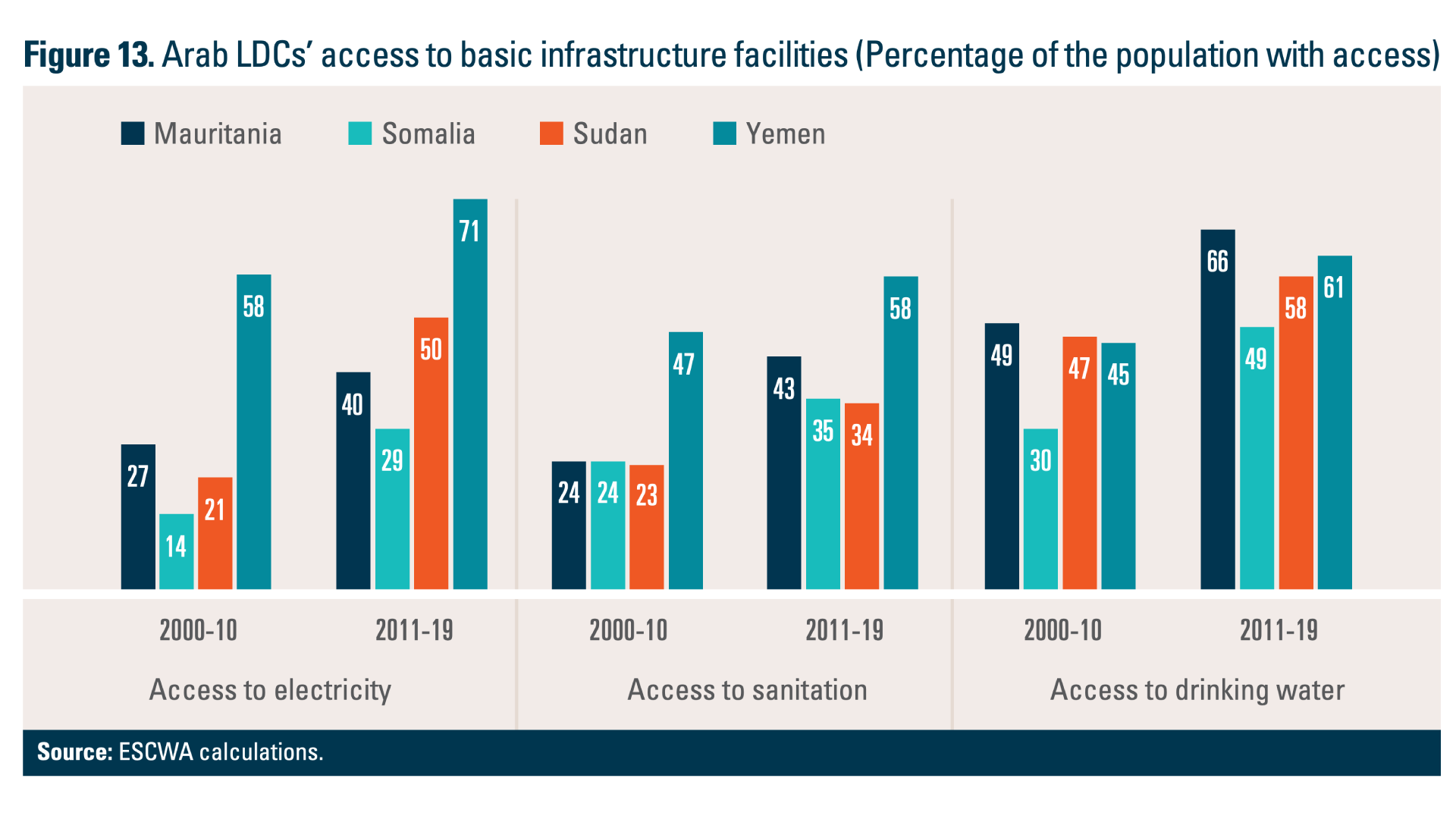

● Support infrastructure needs that are in the public interest, such as:

- Electricity at accessible prices, privileging renewable energy;

- Roads, railways and air connections, minimising negative climate side-effects.