Estimating the economic costs of child marriage in the Arab region

Acknowledgements

Key messages

Executive summary

Literature review

Objective of the study

Data sources and methodology

Constraints and limitations

Prevalence of child marriage: National and sub-national patterns

Key mechanisms of the economic costs of child marriage

Economic costs

Conclusion

Policy recommendations

Annex, References,Abbreviations and acronyms,Glossary,Background

download

Full Report

previous studies

Previous studies

Child marriage is a human rights violation and a development challenge that impedes progress

towards the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The elimination of this practice is at the

heart of concerted efforts by ESCWA, UNICEF, UNFPA, and UN Women, who are jointly committed to

tackling this issue. They have spearheaded a series of studies examining the economic

repercussions of child marriage in the Arab region. The initial study, "Estimating the cost of

child marriage in the Arab region: Background paper on the feasibility of undertaking a costing

study," sheds light on the severe consequences of this practice. It offers insights into the

extent, causes, and impacts of child marriage in the region and emphasizes the importance of

quantifying its economic costs. This paper underscores the urgency of eradicating child marriage

to promote gender equality, empower women, and improve maternal and child health.

The second study in the series entitled “The cost of child marriage over the life cycle

of girls and women: Evidence from Egypt, Iraq, Jordan and Tunisia” delves into the life-cycle

costs associated with child marriage, assessing its effects across different stages of a woman’s

life. Focused on Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Tunisia, the study reveals the far-reaching and

profound effects on women’s health, education, and economic status, thereby enriching our

understanding of the long-term strain caused by this harmful practice. This piece of research

not only quantifies the costs of child marriage on human development but also provides a roadmap

for its economic evaluation.

The third and latest study, “Estimating the economic costs of child marriage in the

Arab region," expands on previous findings by conducting a more detailed demographic, health and

economic analysis. This comprehensive report highlights the significant impact of child marriage

on the region's economy, estimating a potential increase of about 3 percent per annum to the

Arab region's economy, amounting to approximately $3 trillion (US dollars) between 2021 and 2050

if child marriage is eliminated. The failure to address this issue, on the other hand, would

lead to substantial economic challenges.

Together, these studies present a compelling narrative about the extensive and varied

economic implications of child marriage in the Arab region. Each successive study contributes to

a deeper understanding of this critical issue, advocating for thorough and effective policy

interventions to combat this pressing social problem. These reports collectively underscore the

necessity for comprehensive action, including improvements in family planning, healthcare,

education, and labor market opportunities for women, to prevent child marriage and mitigate its

detrimental economic impacts in the region.

The cost of child marriage over the life cycle of girls and women

Evidence from Egypt, Iraq, Jordan and Tunisia

download webpage link

Estimating the Cost of Child Marriage in the Arab Region

Background Paper on the Feasibility of Undertaking a Costing Study

download webpage link

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

The present report for computing the economic costs of child marriage in Arab economies was

collaboratively developed by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia

(ESCWA), the United Nations Population Fund Arab States Regional Office (UNFPA ASRO), the United

Nations Children’s Fund Middle East and North Africa Regional Office (UNICEF MENARO), and the

United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN-Women). Srinivas

Goli, Associate Professor at the Department of Fertility and Social Demography, International

Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) in Mumbai, served as the Lead Consultant for this

report. Supporting Srinivas Goli were other researchers, including Harchand Ram, Shubhra Kriti,

Shalem Balla and Somya Arora from IIPS, as well as Neha Jain, Assistant Professor at the

Department of Economics, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade (IIFT) in Delhi.

The researchers would like to express their deep gratitude to Ruchika Chaudhary, Gender

Economist (Economic Affairs Officer) in the Gender Justice, Population and Inclusive Development

Cluster at ESCWA, for her supervision, continuous support and invaluable feedback throughout the

entire process, greatly enhancing the research. The study also benefited from the pertinent

contributions of Stephanie Chaban, Social Affairs Officer within the same cluster at ESCWA. Nada

Darwazeh, Chief of the Centre for Women at the Gender Justice, Population and Inclusive

Development Cluster at ESCWA, provided direction, with overall guidance from Mehrinaz El Awady,

the Leader of the Gender Justice, Population and Inclusive Development Cluster at ESCWA.

The report further benefited from the valuable insights and feedback provided by

external peer reviewers, including Aisha Hutchinson (King’s College London), Robert Bain (UNICEF

MENARO), Sajeda Amin (Population Council, New York) and Shatha Elnakib (Johns Hopkins Bloomberg

School of Public Health), whose perspectives greatly enriched the study.

Key messages

Key messages

Eliminating child marriage in the Arab region would have a significant positive impact on economic growth. It is estimated that it could boost the region’s economy by approximately 3 per cent per annum, adding a staggering $3 trillion between 2021 and 2050.

Failure to address the issue of child marriage will result in substantial economic burdens for the Arab region, even with advancements in other socioeconomic, demographic and health measures. If child marriage rates persist, Algeria, Jordan, the State of Palestine, Sudan and Tunisia are projected to experience the highest cumulative GDP losses between 2021 and 2050.

The prevalence of child marriage varies significantly across the region, with rates ranging from 1.5 per cent in Tunisia to 45.3 per cent in Somalia. Additionally, there are variations among provinces within each country. These variations underscore the crucial need for tailored policies and targeted interventions that effectively address and counteract the detrimental consequences of child marriage. Furthermore, Arab countries should strengthen their socioeconomic, population and health policies to mitigate the negative implications of child marriage on women.

Ending child marriage also requires addressing the underlying structural determinants of gender inequality, such as countering discriminatory norms, improving access to quality education, promoting economic participation, providing health-care services, and supporting initiatives to end violence against women and girls. Taking swift action to address these factors will result in greater economic benefits.

Arab countries can avert economic losses by prioritizing key channels, including promoting family planning and maternal and child health care to reduce high fertility and child mortality rates, ensuring access to education for girls both before and after marriage, and creating flexible labour market opportunities that encourage the active participation of women in economic activities.

Executive summary

Executive summary

Child marriage remains a prevalent global practice, with around one in five girls marrying

before the age of 18 in 2022. A considerable variation can also be seen across countries. Child

marriage has been shown to have lifetime consequences for girls in terms of poor educational,

health and economic outcomes, depriving them of their basic rights and leaving the next

generation at a disadvantage. The issue has been aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic and demands

effective and conscious intervention, especially in the poorest countries that exhibit the

highest rates of child marriage. Despite a declining trend in child marriage, the current rate

in the Arab region remains sizeable, with a wide variation across countries. While the

prevalence of child marriage across the Arab region has dropped from one in three to one in five

females, progress has stagnated over the recent decade. A growing volume of studies are

increasingly demonstrating the negative effects of child marriage on a variety of developmental

outcomes; however, concerted efforts and resources to neutralize the practice remain inadequate

across the Arab region. To stimulate greater efforts towards eliminating child marriage, the

present study underlines the economic costs of child marriage and the key mechanisms for a

number of Arab countries. The report offers essential insights into the economic consequences

(cost of inaction) if child marriage is neglected in Arab countries. It serves as valuable

material for advocacy efforts, aiming to draw governments’ attention to this pressing problem.

Economic costs are channelled through demographic, social and health implications

generated as a consequence of child marriage. Demographic implications comprise unwanted

pregnancies and unsafe abortions that alter future population growth, mother and child survival,

and reproduction. Social implications comprise the loss of educational attainment by girls who

are married as children, which eventually harms the exercise of their basic rights, agency,

decision-making ability, earning prospects, community support and empowerment in general. Health

implications include adolescent pregnancies and births, and the high fertility and maternal

morbidity and mortality rates for women marrying early. These implications, endured by girls who

marry as children, might be direct or indirect, as well as monetary or non-monetary, for

individuals and households and cumulated at the State level.

The Phase I report, developed by ESCWA, UNFPA ASRO, UNICEF MENARO and UN-Women (2023)

and entitled “The cost of child marriage over the life cycle of girls and women: evidence from

Egypt, Iraq, Jordan and Tunisia”, studied the costs of child marriage borne by women and girls

in the Arab region. Building on the earlier report, Phase II of the study extends the findings

to measure the “economic costs of child marriage” for 13 of the 22 Arab countries for which the

relevant data is available. The study aims to report the economic costs of child marriage in

terms of the percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) loss for Arab countries. It also

theoretically discusses the multiple ways in which child marriage affects women and girls at the

individual level with repercussions on their families and thereby the State.

Building on earlier work and following a more robust procedure, the present report

utilizes a wider spectrum of demographic, health, education and economic input indicators in the

costing exercise, utilizing a life course perspective to project the economic cost of child

marriage in the Arab region up to 2050 with the base year of 2001. It covers the entire

productive timeline of a girl who married at the age of 15 around the year 2000. The data for

input indicators was compiled from multiple sources, primarily nationally representative

household surveys, including the Demographic and Health Survey, the Multiple Indicator Cluster

Survey and the Labour Force Survey.

Overall findings suggest that the percentage of GDP lost due to child marriage across 13

Arab countries in 2021 was 3.2 per cent and is expected to be 3 per cent in 2050. The cumulative

GDP loss is anticipated to stand at around $3 trillion between 2021 and 2050. Regionally, in

2021, Algeria, the State of Palestine, the Sudan and Tunisia showed more than 4 per cent of GDP

loss attributable to child marriage, while Qatar and the Syrian Arab Republic lost the lowest

GDP (less than 1 per cent). Between 2021 and 2050, Algeria, Jordan, the State of Palestine, the

Sudan, and Tunisia are estimated to lose the highest cumulative GDP attributable to child

marriage if current child marriage rates persist.

It is important to note that the economic cost of child marriage not only depends on the

rates of child marriage but also on the differences in demographic and socioeconomic outcomes

between females married below 18 years of age and those married at 18 and above. Therefore,

Algeria, Jordan and Tunisia will incur greater economic costs attributable to child marriage

because they have greater fertility and educational differences across females married below 18

years of age than those married at 18 and above. On the other hand, countries like Iraq and

Mauritania have higher child marriage prevalence rates, but the relative differences in

fertility rates and educational levels between those married below 18 years of age and those

married at 18 and above are not as high as in Algeria, Jordan and Tunisia, thus incurring lesser

economic costs that are attributable to child marriage.

Our estimate (3.2 per cent in 2021 for the Arab region) is higher than earlier studies

covering emerging and developing countries (1 per cent) and South Asia, the Middle East and

Africa (1.4 per cent). There could be two reasons for this discrepancy: (1) the difference in

the geographical coverage across all three studies; or (2) the difference in the procedure of

estimation and the number of input indicators considered for the model. The current study is

more comprehensive in terms of indicators inputted for the model. However, the total GDP

estimates across the 13 Arab countries from this study are in tune with the World Bank estimates

for the respective countries.

In terms of policy implications, the present study highlights that the extent of child

marriage significantly contributes to the failure of States in achieving their economic

potential. The variations in the economic cost of child marriage, measured by GDP loss, within

the Arab region stem from two key factors: the prevalence of child marriage and the

effectiveness of countries’ health-care and socioeconomic systems. It is imperative for Arab

countries to take action in preventing child marriage and mitigating the associated demographic,

health and economic impacts. By addressing critical channels such as promoting family planning

and maternal and child health care to reduce high fertility and child mortality rates, ensuring

access to education for girls before and after marriage, and creating flexible labour market

opportunities to encourage women’s participation in economic activities, countries can avert

economic losses.

1. Literature review

Global literature on child marriage is heavily skewed towards social, demographic and health

implications. In particular, most of these studies have reported differences in health,

education and employment outcomes for girls married before and after turning 18 years old.

Few studies have documented the economic cost of child marriage, particularly the

macroeconomic costs (e.g. percentage of GDP loss due to child marriage). The literature

constraint is more significant for the Arab region than other regions of the world; thus, we

have utilized both global and Arab region studies to build conceptual and analytical

frameworks for the current study. We have organized the literature review into three

sections: (1) drivers of child marriage; (2) economic costs; and (3) child marriage in the

context of the Arab region.

Drivers: The documentation on child marriage consistently

highlights several structural factors that generate and intensify child marriage, ranging

from economic factors such as poverty and limited work opportunities; sociocultural factors

such as education, social practices, religious beliefs, ethnicity, class and gender norms;

and political factors such as instability, including conflict, displacement and natural

disasters. All these factors jeopardize a girl’s voice and autonomy, putting her in the loop

of early marriage and its eventual consequences. The poorest countries, regions and

households often confront the greatest prevalence of child marriage, with poor girls

residing in rural regions as the most vulnerable. Moreover, the lack of work opportunities

for girls due to social norms and practices may cause parents to consider it unnecessary to

invest in their schooling.

More often than not, as the growing evidence shows, the level of education tends to

determine a girl’s age at marriage; as such, lower education attainment is associated with a

lower age at marriage. Furthermore, child marriage has been demonstrated to be deeply

entrenched in social practices and traditions. Diverse settings serve as drivers for child

marriage that are prevalent in respective set-ups, notably the practice of dowry or bride

wealth, which can generate instant economic gains for a family; community pressure to

conform to societal norms; using the marriage of girls to settle family disputes; the fear

of sexual harassment or sexual violence; the desire to control girls’ sexuality to avoid

unwanted pregnancies or jeopardizing the family’s honour; and internalized social norms

whereby girls themselves desire to marry early due to perceived vulnerabilities and a lack

of alternatives.

Conflict and war impact women and girls in uniquely gendered ways, albeit varying

based on the location, earnings, social set-up and cultural setting. Conflict-induced

instability generates fear of injury and death, escalates incidents of sexual violence,

triggers food insecurity and deepens gender stereotypes. Such instability leads to a low

mean age for females at the time of marriage, higher child marriage rates and low female

literacy rates. For families in conflict zones, child marriage becomes a negative coping

mechanism to “save” the girl from perceived exploitation while conserving limited resources

by passing responsibility for her to another household. Child marriage, therefore, can be

interpreted as a social exchange of girls by the family to maximize their resources and

safety nets.

The economic costs of child marriage: Age at marriage is a

significant determinant of population dynamics, given that it sets the foundation for

forthcoming factors in deciding a girl’s quality of life. While child marriage is widely

addressed as a human and women’s rights issue, lately, studies have highlighted and

quantified the economic costs of child marriage (table 1).

Table 1. Review of literature on multi-country estimates of economic costs of child marriage

The economic cost of violence against women and girls (child marriage, in this case),

defined in the UN-Women report “The costs of violence”, is the direct and indirect tangible

cost with a monetary value. These could be the private costs endured by young girls and

their next generation, or public costs such as an increased burden on the government’s

health-care and education systems. The total costs tend to have a multiplier effect on GDP

and economic development, triggering the vicious cycle of inter-generational poverty and

inequality.

Child marriage directly lowers women’s work prospects and financial returns due to

low educational levels. At the same time, it indirectly increases the proportion of their

unpaid household work resulting from higher lifetime fertility. To corroborate, Savadogo and

Wodon (2017a) found that child marriage reduces earnings in adulthood for women marrying

early by 9 per cent through its impact on education. In some countries, it has been noted to

affect decision-making and bargaining power.

Therefore, economic costs are the closest channels affecting the GDP of a State

through the low employment rate of women married as children, the low wage rate of their

unskilled jobs, and lower earnings, savings and hence a lower tax generation for the State.

Child marriage in Arab countries: Like many other regions in the

world, the Arab region has patriarchal norms whereby women are expected to prioritize their

family before their own rights as individuals.

This includes the institutionalization of policies that work to preserve the

patriarchal status quo that ultimately governs economic, political and social

decision-making.

In the past decade, conflict has tended to drive the many instances of child

marriage in the region, resulting in refugees and displaced families resorting to the

practice to protect girls from sexual violence and thus safeguard the family’s honour.

In some cases, child marriage is linked to kidnapping and trafficking by armed

groups and militias; the Syrian Arab Republic and Iraq have recorded such instances of the

abduction of girls.

In Jordan, child marriage incidents have increased since the onset of the conflict

in the Syrian Arab Republic in 2011, particularly among Syrian refugees. For example, the

rate of child marriage among Syrian girls in Jordan increased from 33.1 per cent in 2010 to

43.8 per cent in 2015, impacting their sexual and reproductive health in terms of untimely

pregnancies, domestic violence, social alienation, mental health issues and a loss of work

opportunities.

There is strong evidence of the relationship between child marriage and deep-rooted

cultural beliefs and discriminatory gender norms in the Arab region. For instance, in Egypt,

child marriage is linked with community notions related to female genital mutilation (FGM),

while in the Syrian Arab Republic, young girls are persuaded to marry at a young age due to

their sexual inexperience.

Poverty is another factor that engenders child marriage in countries such as Egypt,

Libya, Somalia, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen.

The trend is also noted in Iraq, Jordan and Morocco, where girls in low-income

families, viewed as a financial burden, were twice as likely to marry young than in

wealthier households in 2006–2011.

A study on Syrian refugees in Egypt highlights that underperforming girls in school

were better off married, and girls interested in education were retained in school to

continue their studies and had their marriages postponed.

Among other factors are a worsening economy and growing inflation rates that

negatively impact the survival of low-income families, particularly with young women, in

these regions.

Phase I of this exercise explored the costs of child marriage on women and girls in

four Arab countries and is the only comprehensive study that has highlighted the social and

health costs of child marriage at different stages of women’s lives. Women and girls who are

married young in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan and Tunisia experienced serious ramifications at each

stage of life in terms of fertility, decision-making, education, autonomy, labour force

participation and mortality rates of their children. Hence, Phase II builds on these

findings to focus on the loss of income (or GDP) for the Arab region.

2. Objective of the study

In the Arab region, research has mainly

focused on examining the prevalence

of child marriage, identifying the social,

economic and political factors that drive

this practice, and investigating its harmful

effects on girls and women. While the

Phase I report established a link between

child marriage and various outcomes

related to demographics, health, education

and the labour market, it did not quantify

the economic losses that result from this

practice for the State. To gain a better

understanding of the actual short- and

long-term economic costs that women,

their families and the Government will bear,

it is crucial to evaluate the impact of child

marriage on the GDP of all Arab countries.

Therefore, the goal of this study is to

conduct a cost analysis that measures the

impact of child marriage on the GDP of

countries, with the aim of strengthening

the case for eradicating this practice

in the region. The study advances

recommendations to reduce the economic

burden of child marriage by taking

proactive steps to address the intermediate

channels that contribute to economic

implications.

The present study employs the spectrumbased

simulation model and incorporates

a wide range of input indicators to provide

a detailed analysis of the demographic,

social and macroeconomic costs

associated with child marriage. Unlike

Mitra and others (2020), the present

study does not rely solely on a macroregression

model approach. Instead, its

hierarchical and component simulation

approach enables the inclusion of more

input parameters and the estimation of

a larger number of outcome indicators.

Moreover, the model used in the study not

only projects the cost of inaction on child

marriage as a percentage of GDP loss but

also includes other key demographic and

health indicators up to 2050, covering the

entire productive lifespan of a girl who was

married at age 15 around the year 2000.

Conceptual framework: Mechanisms of the economic costs of child marriage

Child marriage incurs economic costs through multiple channels, as depicted in figure 1. This practice has demographic implications such as high fertility levels, early childbirth and population growth, which directly impact economic outcomes. Child marriage also disrupts educational attainment, leading to limited decision-making ability, particularly in terms of reproductive choices, instances of gender-based violence against women and low labour force participation, resulting in poor health status and low earnings. Poor health conditions and higher disability and mortality risks further exacerbate household financial conditions. The effects of child marriage are also intergenerational, as they hinder the creation of human capital in future generations. Poor wage earnings and household savings result in lower tax returns for the State, while poor health conditions lead to greater State spending on health care. Thus, the State economy is affected from both the savings and expenditure ends.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework: Mechanisms of the economic costs of child marriage

3. Data sources and methodology

A. Data sources

Comparatively, the Arab region lacks the

availability of reliable and consistent data

to measure and monitor child marriage and

its causes and consequences. Recurrent

conflicts and geopolitical issues in the region

worsen the global periodic surveys critical

for cross-country comparisons. Of the 22

countries that constitute the Arab region, only

13 countries had relevant data for the time

period under consideration (2001–2020). For

the exercise of costing child marriage in this

region, the data for the input indicators was

collected and compiled from multiple sources

for the period 2001–2020. The data sources

used for analysis include: (i) demographic

health surveys (DHS); (ii) multiple indicator

cluster surveys (MICS); (iii) labour force

surveys (LFS); (iv) United Nations World

Population Prospects; (v) world development

indicators (WDI); (vi) United Nations Model

Life Table (West Asia Model); (vii) countryspecific

censuses from Arab countries;

and (viii) official statistics of the respective

Arab countries. The present study adopted

interpolation and extrapolation methods to

fill the data gaps between any years.

Globally, the DHS is the largest data source for

population, health, human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV) and nutrition and is internationally

comparable and surveyed in about 90

countries. Some of the Arab countries have

been covered under the DHS programme,

such as Egypt (2014, special DHS in 2015),

Jordan (2017/2018), Mauritania (2019–2021),

Morocco (2003/2004), the Sudan (1989/1990),

Tunisia (1988) and Yemen (2013). The MICS is

the largest source of reliable internationally

comparable data on women and children

globally and has been carried out once or

more in 118 countries. The latest MICS within

the Arab region are: Algeria (2018/2019), Egypt

(2013/2014), Iraq (2018), Mauritania (2015),

Oman (2014 restricted), the State of Palestine

(2018/2019), Qatar (2012), Somalia (2011), the

Sudan (2014), the Syrian Arab Republic (2006),

Tunisia (2018) and Yemen (2006). Although the

Pan Arab Project for Family Health (PAPFAM)

is available in Libya, the study excluded Libya,

due to a lack of information comparability in

PAPFAM with the DHS and MICS, and Oman,

due to a lack of access to the microdata.

Overall, the study covers 13 Arab countries

that have microdata from the latest available

DHS or MICS.

In addition, we collected information on

employment and unemployment from

the WDI, LFS and official statistics of the

respective countries. The total and projected

population data were collected from the

countries’ censuses and United Nations World

Population Prospects, respectively. The study

used the most suitable model life table from

two sets of standard model life table families

to derive a variety of mortality indicators

and underlying mortality patterns for the

estimation and projection of the population

for each country. The data on the base year

GDP in United States dollars ($), annual GDP

growth rate (%), and urbanization (%) were

collected from the WDI. In addition, education

and health-related indicators were compiled

from multiple data sources including DHS,

MICS, censuses, and official statistics of the

countries (see the details in annex table 1).

B. Approach

The linkage between child marriage and

economic growth is not straightforward

because it directly correlates with

some “conventional” economic growth

determinants such as fertility, education,

health and employment, among others.

Wodon and others (2017) outlined five

main channels – health, education, fertility,

labour force participation and decisionmaking

– through which child marriage

impacts economic growth. In their analytical

model, Wodon and colleagues further

consolidated these channels into human

capital (i.e. education and health), as there is

a significant overlap across these channels.

Later, the study by Mitra and others (2020)

also recognized the interdependence

between health, education, economic growth

and other intermediates operating under the

costing exercise of child marriage.

Following Wodon and others (2017) and

Mitra and others (2020), this study used

four sets of parameters (i.e. demographic,

health, education and economic) in the

costing exercise of child marriage in a life

course perspective. Child marriage is like

a silhouette on lifetime outcomes, as it

affects skill formation, health and economic

consequences at all stages of life. In this

study, by saying “life course”, we mean

the estimates are cumulative economic

costs of child marriage associated with

education, health and labour market losses,

which operate at different stages of an

individual life (box below). Moreover, several

other intermediates – such as women’s

decision-making ability and gender-based

violence against women – that influence

economic outcomes were not included

as separate variables because they are

highly collinear with demographic, health,

education and employment parameters.

Nevertheless, within four broad sets of

parameters (demographic, health, education

and economic), the model used in this study

includes other contingent factors such

as age structure of the population and its

drivers, economic status and its predictors,

and the urbanization level of women’s

country of residence. Figure 2 explains

the complete operational (or analytical)

framework of the simulation model and the

parameters used to estimate the economic

costs of child marriage in the Arab region.

While the present study follows the simulation

approach used by Wodon and others (2017),

its analytical framework for estimating

the economic costs of child marriage is

slightly different and adheres to a more

comprehensive procedure. We have extended

the projection of the economic costs of child

marriage for the Arab region up to 2050 with

the base year of 2001. The period 2001 to 2050

is selected considering the working lifespan

of around 50 years for a female married at the

age of 15. For instance, in this model, a female

who married in the year 2001 at age 15 (base

year for this study) is expected to live up to

65 years (up to 2050, a goalpost year for this

study) as a worker or a non-worker. However,

the input indicators are not available for all

countries from 2001. In such cases, the base

year has been chosen as per the availability of

the data. The life-cycle approach.

The study used three key modules of the spectrum-based simulation approach: DemProj, FamPlan and RAPID (figure 2). DemProj stands for demographic projection module in the spectrum simulation model. It provides age-sex population base parameters and their projection for the simulation module. The projection function works on a set of assumptions about fertility, mortality and migration for goalpost years.

Figure 2. Analytical framework of the simulation model in the spectrum suite 6.19: Costing of child marriage in Arab countries

The FamPlan module stands for the projection

of family planning parameters. Family planning

inputs are needed to reach national goals for

addressing unmet needs or achieving desired

fertility. For this study, the family planning

module provides necessary parameters that

can predict probable differences in family

planning indicators and their consequences

for the fertility of child-married women and

non-child married women.

Resources for the Awareness of Population

Impacts on Development (RAPID) projects

the social and economic consequences of

high fertility and rapid population growth

for such sectors as labour, education,

health, urbanization and agriculture. For

the simulation model, RAPID provides the

differential probability of socioeconomic

achievements of child-married and nonchild

married input and outcome indicators.

A detailed explanation of these modules is

presented in annex table 2.

The study also differs in terms of its outcome

measures. We have provided macro-level

demographic and health costs alongside the

economic costs (GDP loss) for three different

scenarios. These three scenarios include:

(i) child marriage scenario – a hypothetical

case where we assume all women across

the Arab region are married below the age

of 18; (ii) non-child marriage scenario – the

best hypothetical case where we assume

that all women across the Arab region are

married at 18 years of age or above; and (iii)

overall scenario (as usual scenario) – a case

where the status quo continues, that is, child

marriage continues to prevail at the current

level in the Arab region.

4. Constraints and limitations

Despite implementing a robust approach to estimate the cost of child marriage, it is important to acknowledge the existence of certain data-related limitations and constraints in this research. The estimation of the economic consequences of child marriage utilizing a macro-level simulation model necessitates a wide range of input indicators, including population age-sex distribution,35 fertility rates, contraceptive usage, mortality rates (such as infant mortality, under-5 mortality and maternal mortality), education levels, health status, labour force participation, urbanization, agriculture and GDP per capita. These input indicators are predominantly obtained from sources such as censuses, sample surveys like DHS, MICS and LFS, as well as vital registration and official statistics from respective countries. In this study, the most recent available data was utilized, and extrapolation of input indicators was performed when required. It is important to note that the consequences of child marriage are intricate and hierarchical in nature. Consequently, any costing exercise conducted through a macro-level simulation model tends to underestimate rather than overestimate the true impact, as it is impossible to include all parameters directly and indirectly influenced by child marriage.

5. Prevalence of child marriage: National and sub-national patterns

The study presents the national and

sub-national patterns of child marriage

prevalence for the 13 Arab countries

included in this study (figures 3 and 4).

According to the United Nations World

Population Prospects (2022), these 13

countries contribute 80 per cent of the

population in the Arab region.

There is considerable variation in the

prevalence of child marriage across the

region and among provinces within each

country. With 3.8 per cent of women married

below 18 years of age at the national level

in 2018/2019, Algeria is the second lowest

in terms of the prevalence of child marriage

among the countries investigated in this

report. Despite the country’s low prevalence

of child marriage, there is considerable

variation in the sub-national pattern. Across

the seven regions in the country, the child

marriage rate ranges from as low as 0.6

per cent in Nord Est to 6.2 per cent in

Hauts Plateaux.

Figure 3. Prevalence of child marriage in Arab countries

As the most populous country in the Arab

region, Egypt contributes around 24 per cent

of the population. At the country level, child

marriage prevalence stands at 17.4 per cent

as at 2014. However, there are considerable

variations among the provinces, with Fayoum,

Beni Suef and Giza showing as high as

27 per cent, 26 per cent and 25 per cent,

respectively, and Suez showing just 4.4 per cent

of females married before the age of 18.

Iraq constitutes 9 per cent of the total

population of the Arab region. In terms of

the prevalence of child marriage, with 28

per cent of women married before 18 years of

age, Iraq stands among the top five countries

regionally. Moreover, the sub-national

pattern indicates a significant variation

across the 18 provinces. The child marriage

rate is lowest in Duhok with 8.14 per cent and

highest in Misan with 44 per cent. Najaf (37.2

per cent), Karbala (37 per cent), Thi-Qar (35

per cent), Basrah (33.5 per cent), Diala (32

per cent) and Nineveh (31 per cent) exhibit

more than 30 per cent of women marrying

before the age of 18, as at 2018.

With 9.7 per cent of females married

below 18 years of age at the national level

in 2017/2018, Jordan shows a moderate

prevalence of child marriage in the region.

Jordan also shows a considerable variation

in the sub-national pattern of child marriage

prevalence. Across the 12 governorates in

the country, the child marriage rate ranges

from as low as 3.27 per cent in Tafilah to 15.4

per cent in Mafraq.

In terms of the prevalence of child marriage,

with 36.6 per cent of females married

before the age of 18, Mauritania stands in

second place among all the Arab countries

considered for the study. Besides, the subnational

pattern also indicates a significant

variation across the 14 regions. The child

marriage rate is lowest in Nouakchott-Ouest

at 16.5 per cent and highest in Guidimaka at

57.3 per cent. Gorgol (50.3 per cent), Hodh

Ech Chargui (49.7 per cent), Assaba (46.2

per cent) and Hodh El Gharbi (43.7 per cent)

depict more than 40 per cent of females

marrying before age 18 as of 2019–2021.

The average child marriage rate in Morocco

is 16 per cent as at 2003/2004. Within the

country, the percentage of females married

before the age of 18 varies from 7.7 per cent

in Grand-Casablanca to 29.4 per cent in

Laâyoune-Boujdou-Sakia Al Hamra.

With 13.4 per cent of females married

below 18 years of age at the national level

in 2019/2020, the State of Palestine shows

a moderate prevalence of child marriage

in the region. The State of Palestine also

indicates a substantial difference in the

sub-national pattern of child marriage

prevalence. Across the 16 governorates, the

child marriage rate ranges from as low as

5.3 per cent in Tulkarem to 22.8 per cent in

North Gaza.

With an average of 4.2 per cent of females

marrying before they are 18 years old in

2012, Qatar shows one of the lowest levels

of child marriage prevalence in the Arab

region. However, within the country, the

percentage of females married before age

18 varies from 0 per cent in Al-Shamal and

Al-Wakra to 13.36 per cent in Al-Daayen.

The average prevalence of child marriage

in Somalia is 45.3 per cent, which is the

highest among all the Arab countries

included in this study. Across the regions,

the prevalence of child marriage varies

considerably. It ranges from 12 per cent in

Awdal to 90 per cent in Middle Juba. Ten

out of 18 regions in the country have more

than the national average (i.e. 45 per cent

and above).

The Sudan is the second largest country,

contributing around 10 per cent of the

population of the Arab region. At the country

level, the child marriage prevalence rate in

the Sudan stands at 34.2 per cent as at 2010.

However, there are considerable variations in

child marriage prevalence across 18 states,

ranging from 56 per cent in Central Darfur to

17.6 per cent in River Nile. South Darfur (52.3

per cent), Blue Nile (49.6 per cent), El Gadarif

(47.5 per cent), East Darfur (46.3 per cent),

West Darfur (45 per cent), South Kordofan

(43.7 per cent) and Kassala (40.6 per cent)

have over 40 per cent of females marrying

before they are 18 years old.

With an average of 13.3 per cent of females

marrying before 18 years as at 2012, the

Syrian Arab Republic shows a moderate

child marriage prevalence in the Arab region.

However, within the country, the percentage

of females married before the age of 18

varies from 4.7 per cent in Tartus to 26

per cent in Quneitra.

At the country level, with an average child

marriage rate of 1.5 per cent as at 2018,

Tunisia shows the lowest prevalence among

the 13 Arab countries included in this study.

Even within the country, the percentage of

females married before the age of 18 does not

vary significantly.

With an average of 32 per cent of females

marrying before 18 years as at 2013, Yemen

stands in the top five countries in terms of

child marriage prevalence in the Arab region.

Also, the country shows huge sub-national

variation across its 21 governorates. The

percentage of females married before age

18 varies from 50.5 per cent in Dhamar to

10 per cent in Aden. Besides Dhamar, three

other governorates (Al-Jawf, Al-Mhweit and

Raymah) show a child marriage prevalence

rate of more than 40 per cent.

Figure 4. Prevalence of child marriage at the provincial level in selected Arab countries

6. Key mechanisms of the economic costs of child marriage

Both in its conceptual and empirical model, the study presents several mechanisms through which child marriage induces economic costs for a country. Following the assertion made by Wodon and others (2017) that “the impacts of child marriage are large for fertility, population growth, education as well as labour market outcomes”, the present chapter empirically discusses these key indicators, which are also the critical mechanisms for the economic costs of child marriage in the simulation model of the study. Also, with the support of previous studies on the subject from another geographical context, the chapter discusses how fertility, infant mortality, education, women’s labour force participation, and household economic and health costs are endogenous to several other indicators, as exhibited in the conceptual and empirical model used for estimating the economic costs of child marriage in this study.

A. Fertility differences by age at first marriage

One of the known determinants of economic growth is population growth. Population growth is greatly influenced by fertility rates. High fertility rates are a key implication of child marriage. High fertility also reflects the high number of both unwanted pregnancies and births. A higher number of births is a mechanism through which child marriage affects the State economy. The study thus analyses the fertility differences in association with the age at first marriage for a thorough understanding of the phenomenon. Though age at first birth is also indicative of the same, the study avoids using it owing to a high endogeneity between age at first marriage and first birth.

Table 2. Total fertility rate by women’s age at first marriage in Arab countries

Total fertility rate (TFR) is a key measure of fertility that refers to the average number of children born per woman over their lifetime. In table 2, we show the TFR differences across females married below 18 years of age and for those who married at 18 and above. The findings suggest considerable but varying fertility differences for females married below 18 years and those married at 18 years and above across the 13 Arab countries. For instance, in Algeria, females married below age 18 have a TFR of 4.1 compared to only 1.9 among those married at 18 years and above. The largest fertility differences by age at first marriage are found in Tunisia where females married below 18 years of age have 2.5 times higher fertility than their counterparts. Among other countries, Egypt, the State of Palestine and Morocco have more than double the fertility rates among females married below 18 years of age compared to those married at age 18 and above. Despite having higher fertility rates, Mauritania, Iraq, Yemen and the Syrian Arab Republic show lesser fertility differences by age at first marriage. In contrast, the Sudan and Somalia have higher fertility rates and higher differences by age at first marriage. The least differences are found in Qatar and Iraq.

B. Infant mortality differences by age at first marriage

Population health is also a recognized human capital factor of economic growth that expresses its impact both directly and indirectly. Population health directly determines the quality of human capital, while it has an indirect bearing on economic growth through its influence on population growth.42 The infant mortality rate (IMR) and under-5 mortality rate (U5MR), which refer to child deaths below 1 year and below 5 years per 1,000 live births, respectively, are sensitive population health indicators. These are not only key measures of child health but also for maternal and child health care. Mortality among infants and children is higher among adolescent mothers compared to their counterparts married above the age of 18.43 This generates from multiple avenues such as the young mother’s malnutrition affecting the children’s nutritional status, her restricted decision-making regarding reproductive choices and access to health care, limited agency and mobility, and low knowledge attainment on the matters of contraception and sexually transmitted infections.44 The IMR and U5MR differences across females married below 18 years of age and those married at 18 and above are shown in table 3.

Table 3. Infant mortality differences by women’s age at first marriage in Arab countries

The findings suggest sizeable but varying IMR and U5MR differences for females married below 18 years of age and those married at 18 years and above across the 13 Arab countries included in this study. For instance, Somalia has the largest difference (2.6 times) in IMR among females married below 18 years of age compared to those married at 18 years and above. In Algeria, the childhood mortality rates among females married below the age of 18 are almost double those of women who were married above age 18. The rest of the countries have a difference in childhood mortality rates ranging from 1 to <2, with children of females married below 18 years of age faring worse for all the countries compared to women married at the age of 18 years and above. A similar pattern of differences by age at first marriage is also found in the case of U5MR.

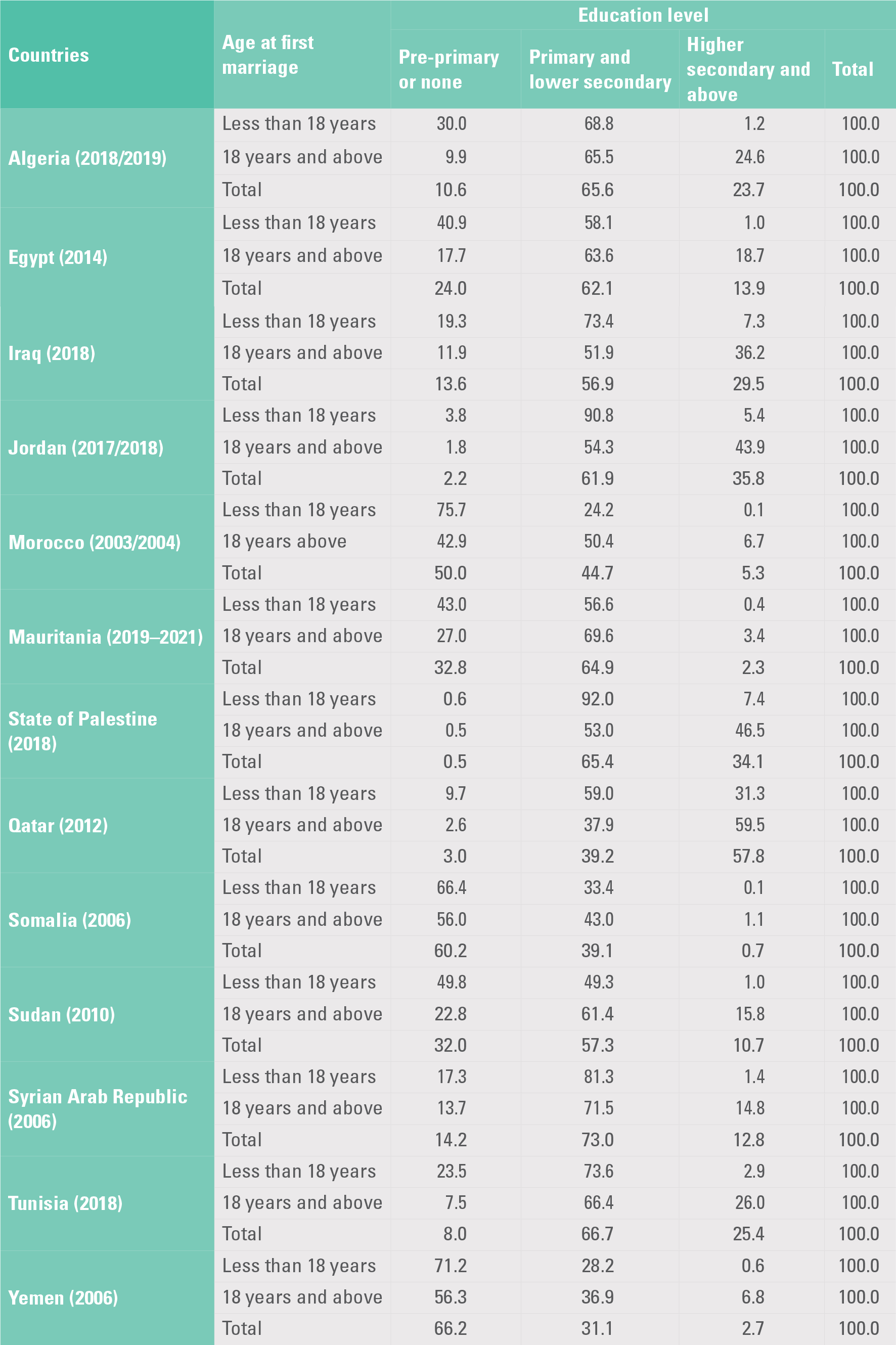

C. Educational differences by age at first marriage

Education is a key human capital measure that predicts economic growth.45 Disruptions in the educational attainment of childmarried women are widely recognized in the literature. Females married below 18 years of age are less likely to enter higher education compared to women married at higher ages.46 Lower educational levels for women bring poor social and economic outcomes not only to the individual but to the respective households and the State as well.47 Thus, education is a mechanism through which child marriage may affect the State economy. Table 4 presents educational differences by age at first marriage. Findings suggest considerable but varying differences in higher education across women married below 18 years of age and those above 18 years of age. For instance, in countries like Algeria and Morocco, the difference in higher education among females married below 18 years of age and those who married at the age of 18 and above is 20 and 67 times, respectively, while the differences are the least in Qatar (2 times) and Iraq (5 times). Other countries, such as Egypt, Somalia, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen, show higher educational attainment ranging among women married at and above 18 years of age compared to females married below 18 years of age. Differences in the education levels for Jordan, Mauritania, the State of Palestine and Tunisia are around seven times on average, with women married at the age of 18 and above faring better in all these countries.

D. Workforce participation rate by age at first marriage

The workforce participation rate of a population has a direct bearing on a household and country’s economic prospects, while child marriage has an effect on the individual’s participation in the labour market.48 Even so, a male’s labour force participation increases after marriage while a female’s declines. The ILOSTAT, using data from 107 countries, has revealed that men have a higher level of participation in the labour force than females, while this gender gap is worsened for married men and women.49 Furthermore, childbearing also decreases the participation among females.50 Table 5 presents the differences in participation in the labour market by married females below 18 years of age and women married at 18 years and above for those in the age group of 15-49 years for five Arab countries. The findings suggest considerably low but varying differences in the workforce participation rate for females married below 18 years of age compared to those married at 18 years and above. For instance, the workforce participation rate for females married below 18 years of age in Algeria is nearly three times less with reference to those married at 18 years and above. Even in Morocco and Egypt, the differences in women’s workforce participation rate are considerably low for females married below 18 years of age compared to those married at 18 years and above. Furthermore, Mauritania and Yemen also exhibit a lower workforce participation rate for females married below 18 years of age compared to those married at 18 years and above.

Table 5. Workforce participation rate by women’s age at first marriage in Arab countries

7. Economic costs

A. Macroeconomic costs: GDP lost due to child marriage

Table 6 shows the percentage of GDP lost

due to child marriage across the 13 Arab

countries included in this study. In 2021,

Algeria lost the highest percentage of GDP

(5.1 per cent), while Qatar lost the lowest

percentage of GDP (0.1 per cent). Ten

countries lost over 2 per cent of their GDP,

with the State of Palestine, the Sudan and

Tunisia losing over 4 per cent (4.3 per cent,

4.9 per cent and 4.3 per cent, respectively).

The remaining three countries had lower

than 2 per cent of their GDP lost due to child

marriage, with only Qatar and the Syrian Arab

Republic below 0.5 per cent (0.1 per cent and

0.3 per cent, respectively).

It is important to note that the economic

cost of child marriage not only depends

on the rates of child marriage but also

on the differences in demographic and

socioeconomic outcomes between females

married below 18 years of age and those

married at 18 years and above. Therefore,

Algeria, Jordan and Tunisia will incur

greater economic costs attributable to child

marriage because they have greater fertility

and educational differences across females

married below 18 years of age than those

married at 18 years and above. While, for

countries like Iraq and Mauritania, despite

having higher child marriage prevalence

rates, the relative differences in fertility rates

and education levels between those married

below 18 years of age and those married at

18 years and above are not as high as those

in Algeria, Jordan and Tunisia, thus incurring

lesser economic costs that are attributable to

child marriage.

Given the model used in this costing exercise,

the trends remain more or less the same in

the projected years. In 2050, the Sudan is

projected to lose the highest percentage of its

GDP (5.1 per cent), while Qatar is projected to

lose the lowest at 0.1 per cent. Eight countries

are projected to lose over 2 per cent of their

GDP due to child marriage, with the average

being 4.06 per cent. The remaining five

countries – Iraq, Mauritania, Qatar, Somalia

and the Syrian Arab Republic – are forecasted

to lose less than 2 per cent of their respective

GDP, implying that good socioeconomic and

health resources could help avoid the high

economic costs of child marriage.

The estimated economic cost of child

marriage for the Arab region stood at 3.2

per cent in 2021 and will be 3 per cent in 2050.

Table 6. Economic costs: Percentage of GDP lost due to child marriage in Arab countries

In absolute terms (table 7), child marriage

had an economic impact of $40.7 billion in

2021, and this figure is expected to increase

to a cumulative total of $3 trillion by 2050.

Among the countries analysed, Egypt had

the highest economic cost in 2021, reaching

$91.3 billion, while Mauritania had the lowest

cost at $0.6 billion. Looking ahead to 2050,

the Sudan is projected to have the highest

cumulative economic cost due to child

marriage, estimated at $18,784 billion, whereas

Mauritania is expected to maintain its position

with the lowest cumulative economic cost at

$66.6 billion.

The prevalence of child marriage has greater

economic relevance for countries with high

rates of child marriage and fertility, and poor

health-care services, such as Algeria, Jordan,

the State of Palestine, Somalia, the Sudan

and Yemen. Across the 13 Arab countries, the

total GDP estimates presented in this study

align with the World Bank estimates for the

respective countries.

Table 7. Economic costs: Absolute difference in GDP for child marriage and non-child marriage scenarios, 2001–2050 (Billions of dollars)

B. Household economic and health-care costs of child marriage

As explained through the conceptual

framework of this study, a part of the

economic cost of child marriage for countries

influences the household as well. Households

with a woman married as a child experience

greater income loss both through wages as

well as excess health-care expenditures.

Earlier, Wodon and others (2017), as well as

Wodon and Yedan (2017b), demonstrated

that the economic participation and wage

earnings for females married at early ages

are significantly less compared to their

counterparts married at higher ages. Wages

have a significant bearing on household

earnings.

This section provides an analysis of the

average annual economic costs borne by

households and the private health-care

costs associated with child marriage.

The findings presented in figure 5 indicate

that households in most Arab countries

face significant average annual economic

costs. For example, seven Arab countries

(Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco,

the State of Palestine and Tunisia) show

average economic costs exceeding $600 per

household, with Algeria having the highest

cost at $1,173 and the Syrian Arab Republic

having the lowest at $37.

Figure 5. Average annual economic cost per household attributable to child marriage, 2021 (Dollars)

The estimated average annual healthcare costs for households also show considerable variation among the countries. The range spans from $292 in Jordan to a mere $5 in the Syrian Arab Republic. Additionally, only four countries (Algeria, Jordan, Morocco, and the State of Palestine) have household health-care expenditures exceeding $100 per year (figure 6).

Figure 6. Average annual health cost per household attributable to child marriage, 2021 (Dollars)

8. Conclusion

Child marriage has been shown to have

lifetime consequences for girls regarding poor

educational, health and economic outcomes,

depriving them of fundamental rights and

leaving the next generation at a disadvantage.

The issue has been aggravated by the

COVID-19 pandemic and demands effective

and conscious intervention, especially in the

poorest countries, which exhibit the highest

rates of child marriage. A growing volume of

studies are increasingly demonstrating the

harmful effects of child marriage on varied

aspects of development outcomes. However,

concerted efforts and resources to neutralize

the practice remain inadequate across the

Arab region. To stimulate efforts towards

ending child marriage, the present study

presents the economic costs of child marriage

and its key mechanisms.

Child marriage has been shown to have

lifetime consequences for girls regarding poor

educational, health and economic outcomes,

depriving them of fundamental rights and

leaving the next generation at a disadvantage.

The issue has been aggravated by the

COVID-19 pandemic and demands effective

and conscious intervention, especially in the

poorest countries, which exhibit the highest

rates of child marriage. A growing volume of

studies are increasingly demonstrating the

harmful effects of child marriage on varied

aspects of development outcomes. However,

concerted efforts and resources to neutralize

the practice remain inadequate across the

Arab region. To stimulate efforts towards

ending child marriage, the present study

presents the economic costs of child marriage

and its key mechanisms.

The respective economic costs of child

marriage for 13 Arab countries have been

estimated from 2001 to 2050. However, the

timeline varies for a few countries due to

the non-availability of data. The estimated

economic cost of child marriage in terms

of total GDP and the percentage of GDP

lost provide compelling evidence that child

marriage induces enormous and exponential

economic costs for the Arab region. The GDP

lost due to child marriage across 13 Arab

countries is estimated at 3.2 per cent for 2021

and projected to be 3 per cent in 2050, with

the cumulative GDP loss around $3 trillion

during the forecasted period. Country-wise,

Algeria and the Sudan were estimated to lose

the highest percentage of GDP due to child

marriage in 2021, while Qatar lost the lowest

rate of GDP.

On the other hand, in 2050, the Sudan (5.1

per cent), Algeria (4.8 per cent) and Tunisia (4.6

per cent) are projected to lose the highest GDP

due to child marriage if the current rate persists.

The country-level differentials in the economic

costs of child marriage in terms of GDP loss

are both due to the level of child marriage

and endowment factors such as the quality of

health care and the socioeconomic system. It

is possible that, despite similar child marriage

rates, some countries have managed to control

the damage caused by child marriage through

better health-care and socioeconomic systems,

thus reflected in the lower percentages of GDP

loss. And some countries, such as the Sudan,

have not experienced a significant difference

in demographic and socioeconomic outcomes

between females married below 18 years of

age and those married at 18 years and above.

Thus, economic costs solely attributable to child

marriage are relatively less despite having a

higher prevalence of child marriage and inferior

demographic and socioeconomic outcomes in

the country.

On the other hand, in 2050, the Sudan (5.1

per cent), Algeria (4.8 per cent) and Tunisia (4.6

per cent) are projected to lose the highest GDP

due to child marriage if the current rate persists.

The country-level differentials in the economic

costs of child marriage in terms of GDP loss

are both due to the level of child marriage

and endowment factors such as the quality of

health care and the socioeconomic system. It

is possible that, despite similar child marriage

rates, some countries have managed to control

the damage caused by child marriage through

better health-care and socioeconomic systems,

thus reflected in the lower percentages of GDP

loss. And some countries, such as the Sudan,

have not experienced a significant difference

in demographic and socioeconomic outcomes

between females married below 18 years of

age and those married at 18 years and above.

Thus, economic costs solely attributable to child

marriage are relatively less despite having a

higher prevalence of child marriage and inferior

demographic and socioeconomic outcomes in

the country.

At the outset, the study finds that the

economic cost of child marriage is

substantial across the Arab region. Our

estimate (3.1 per cent in 2021 for the

Arab region) is slightly on the higher side

compared to the 1.05 per cent reported

by Mitra and others (2020) in the case of

EMDCs and the 1.44 per cent noted by

Wodon and others (2017) in the case of

South Asian, Middle Eastern and African

countries. The higher side estimate from

the current study can be attributed to a

greater number of components (i.e. direct

and indirect costs) considered for the

estimation. The estimated economic cost

of child marriage in this study accounts for

several direct and indirect costs, as shown

in the analytical framework (figure 2). The

economic cost due to child marriage not

only depends on the level of its prevalence

but also on the economies of scale and the

country’s socioeconomic, demographic and

health policies.

From a policy perspective, the study suggests

that Arab countries can increase their

GDP around 3 per cent by eliminating child

marriage. It is important to note that the

current study does not engage in detailed

empirical analyses of all the pathways

through which child marriage impacts

the economy of a State and intervention

strategies to eliminate child marriage

because they are widely documented in the

existing literature. Along with its conceptual

framework, a synthesis of the empirical

evidence found in this study in the context of

previous literature provides insights into the

mechanisms through which child marriage

induces economic costs for a State and also

provides possible intervention strategies to

overcome this consequence. The critical

mechanisms identified are demographic,

social and health implications. Demographic

implications comprise unwanted pregnancies

and unsafe abortions that alter future

growth, survival and/or reproduction.

Social implications include the loss of

educational attainment by girls who are

married as children, which eventually harms

the exercise of their basic rights, agency,

decision-making ability, earning prospects,

community support and empowerment in

general. Health implications include the

high fertility rates of females marrying early

and higher maternal morbidity and mortality

rates. These implications, endured by girls

who marry early, might be direct or indirect,

as well as monetary or non-monetary,

for individuals and households and are

cumulated at the State level.

From a policy perspective, the study suggests

that Arab countries can increase their

GDP around 3 per cent by eliminating child

marriage. It is important to note that the

current study does not engage in detailed

empirical analyses of all the pathways

through which child marriage impacts

the economy of a State and intervention

strategies to eliminate child marriage

because they are widely documented in the

existing literature. Along with its conceptual

framework, a synthesis of the empirical

evidence found in this study in the context of

previous literature provides insights into the

mechanisms through which child marriage

induces economic costs for a State and also

provides possible intervention strategies to

overcome this consequence. The critical

mechanisms identified are demographic,

social and health implications. Demographic

implications comprise unwanted pregnancies

and unsafe abortions that alter future

growth, survival and/or reproduction.

Social implications include the loss of

educational attainment by girls who are

married as children, which eventually harms

the exercise of their basic rights, agency,

decision-making ability, earning prospects,

community support and empowerment in

general. Health implications include the

high fertility rates of females marrying early

and higher maternal morbidity and mortality

rates. These implications, endured by girls

who marry early, might be direct or indirect,

as well as monetary or non-monetary,

for individuals and households and are

cumulated at the State level.

In conclusion, the present study advances the

suggestions put forward by Asha George and

others (2020) that eliminating child marriage

also requires addressing the structural

determinants of gender inequality. The

sooner a Government acts to eradicate child

marriage, the greater the economic savings.

Although the financial costs should not be

the only reason for investing in the end of this

practice, it certainly is a paramount concern.

Arab countries must strengthen their social,

economic, population and health policies to

ensure greater gender equality in education,

health and labour market outcomes. Moreover,

financing to eliminate child marriage ensures

human rights.

9. Policy recommendations

The present chapter sets out policy recommendations for Arab countries based on the research and analysis undertaken for this study, along with other available evidence. The study advances the premise that Arab Governments need to act on two fronts: (1) eliminating child marriage; and (2) neutralizing the negative impacts of child marriage at the individual and household levels. It is well known that ending child marriage is crucial to advancing gender equality; therefore, Governments must address the structural determinants of gender inequality. Hence, countries must tackle harmful gender roles, norms and power relations by adopting holistic and multifaceted policies, as discussed below.

-

A. Design targeted strategies for curtailing or eliminating child marriage in the Arab region

Child marriage persists in the region, highlighting its localized nature and the need for targeted interventions. High-prevalence countries (over 10 per cent) should develop prevention strategies, focusing on “hotspot” areas (provinces, governorates or regions). These efforts should be accompanied by programmes that challenge harmful norms and discrimination, along with the vigilant implementation of nationwide child protection policies and legislation, including closing loopholes related to child marriage. Recent systematic reviews indicate that cash incentive programmes have effectively reduced child marriage rates in various countries.61 Therefore, Arab countries could consider adopting similar initiatives to address this issue.

-

B. Neutralize the adverse impacts of child marriage

Countries should adopt a comprehensive and multifaceted approach to address the adverse effects of child marriage and create an empowering environment for females. This approach should include: (1) strengthening family planning and maternal and child health-care policies to reduce unintended pregnancies, births and avoidable child deaths to lessen the population growth and thereby curtail the economic cost of child marriages in the region; (2) focusing on reducing the fertility and educational differences for girls married before and after turning 18 years old, mainly for countries that experience higher economic costs due to child marriage despite having lower child marriage prevalence; (3) being proactive with educational sector policies to ensure the continuation of girls’ education before and after marriage, particularly alternative learning opportunities after marriage or while pregnant; and (4) developing and implementing flexible labour market policies that support and allow more women to enter the labour market before and after marriage.

C. Strengthen data collection on child marriage and its impacts

To effectively address the problem of child marriage in the Arab region, it is crucial to ensure the collection of reliable and disaggregated data on key indicators. Countries should establish systematic data collection processes to gather accurate and up-to-date information. This can be accomplished by developing comprehensive databases using administrative data systems or conducting sample surveys. Such initiatives will facilitate a deeper understanding of the immediate and long-term effects of child marriage on women, girls, their families, communities and the overall society.

D. Promote multi-stakeholder initiatives for greater financial sustainability

Estimating the economic impact of child marriage is a means to address the short-, medium- and long-term effects of child marriage while adopting a human rightsbased approach. Investing in initiatives to eliminate child marriage not only upholds human rights but also makes economic sense. In this regard, it is crucial for Governments to collaborate with a wide range of stakeholders to secure sustainable funding opportunities and work towards eradicating this harmful practice in the region.